Are you a multidisciplinary mold-breaker?

TED2012 Fellowship applications are now open! Apply here.

Interactive Fellows Friday Feature:

Join the conversation by answering Fellows’ weekly questions via Facebook. This week, Genevieve asks:

Do you think the urge to create art is a universal human quality, or did a group of people ‘invent’ it (say, prior to humans leaving Africa), and then share it with others?

Starting Saturday, click here to respond!

Congratulations on being one of the TEDGlobal 2011 Fellows! How is your first TED Conference going?

It’s been such a great time. The Fellows are all brilliant — that was kind of a given — but they’re also incredibly nice! They’re all so passionate and want to share. Typically when you’re dealing with brilliant people, they’re not always the most personable. But every single one of the Fellows is fantastic. My roommate, Bilge Demirkoz, works at CERN, and I couldn’t have asked for a better roommate. We get to talk particle physics at night, which makes me really happy, because that’s always been a fascination of mine.

I felt great about my talk on Monday during the Fellows’ pre-conference. We had time with a professional speaking coach, and I’m feeling really good going in to my main stage talk coming up on Friday.

And as for my work, Autodesk, one of the sponsors here, takes photographs and turns them into 3-D renderings. I’m chatting with them about possibly doing that for some of the interiors of cave art sites, with all the renderings of geometric signs in their places. I’m excited about possibly partnering with them on this project that could give people a virtual experience of being in the cave.

What got you into studying the geometric signs of cave art?

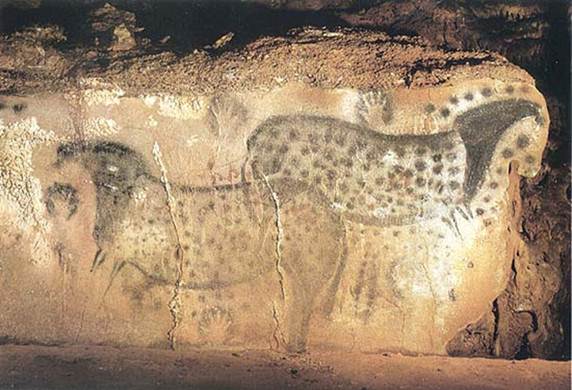

I knew I wanted to be an archeologist since I was a kid. In my last year as an undergrad, I took a class called Paleolithic Art. While I was sitting in the classroom, they were putting up all these beautiful images of animals: rock art in Europe that was done between 10,000 and 35,000 years ago. The animals are amazing — they’re huge, they’re done using perspective, color, and shading … you can see why the animals become the focus and the obsession.

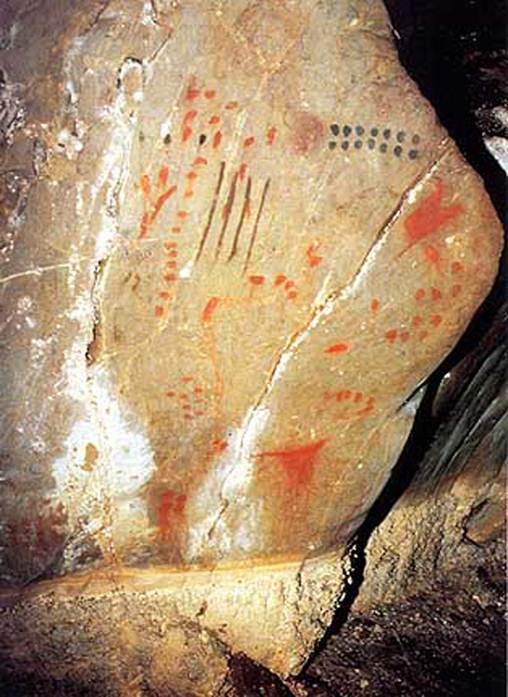

What I kept noticing in the corners and around the edges of the photos, were these little geometric shapes. They were around the animals, on the animals, near the animals … but they were never centered in the photos.

I thought, “What’s going on with these geometric shapes?” I thought it would be a good term paper for my fourth year. So I started looking for articles about them, and I couldn’t find anything. I asked my professor at the University of Victoria, “Am I not looking in the right places? ” And she said, “No, you’re not finding it because it’s never been done.”

We both laughed, and then I said, “Well, that sucks for a term paper.” And she said, “Yeah, but it would make a great grad project.” Funnily enough, I went back and did just that with her in grad school.

What were your goals with this research, and how did you go about conducting it?

When I began doing this, I wanted to know (a) how many shapes there were, and (b) discover if they were using the same shapes across space and time. I realized there wasn’t even a master list documenting how many shapes there were. I actually had to build that myself, creating my own typology as I went along.

I was looking at a 25,000-year time span, considered to be the Ice Age. I wondered if there was any patterning in how the signs were being used. Does it seem random? Are the shapes just little decorative markings, or do they symbolize something more?

It’s not that earlier researchers didn’t want to talk about geometric signs. They just didn’t know what to do with them, because to be able to make a comprehensive database and to search for this kind of patterning, you need technology. That’s what I was able to use: I architected a database for my master’s. I built it in just under four months, and filled it with my data from 150 sites. I went through different reports manually for each site – en français, I might add. These reports are not necessarily written to be fun and exciting.

I used France as the basis of my master’s work, mostly because the French have documented their sites so heavily. They have also spent millions of dollars to carbon date them. In places like Africa — where I swear there’s art that’s got to be in the same age range — the art is red, or it’s engraved, and we don’t know how to date those materials yet.

What made you conclude the symbols weren’t just doodles, tacked in and around the animal paintings?

The biggest clue was patterning. What is probably most convincing and what I’m starting to work on now, is that I found it’s not just that the individual signs are being repeated. We’re starting to see sign clusters in the later half of the Ice Age period (after about 20,000 years ago). They were actually putting them in an order — frequently pairings — of signs. During a preliminary study I did recently, I found that those groupings were replicated at different sites, including across a mountain range.

Perhaps this is due to cultural transmission. We do know people during this time had huge trade routes spanning thousands of kilometers. Or maybe it’s due to migration of the same people. Regardless, it’s really interesting to see how they used the art in a more systematic way.

The system is pretty faint when compared to later-day writing systems, or course. When I talk about things like graphic communication, I am using it in the broader sense. Basically what I’m saying is that the symbols appear to be meaningful to people who were creating them: they were making them on purpose, making choices. So if they were doing this — whether it’s a symbol representing an idea, a thought, a concept — it doesn’t really matter what it actually means, and honestly we have no clue. But what it does suggest is that somebody else could come along and would be able to understand it. This suggests there probably were agreed-upon meanings.

When it comes to these symbols, nothing appears everywhere. They were making choices about what to put and what to omit. Spirals are considered to be one of those basic universals that you always hear people talk about. They are one of the signs we see all over the world, right? But there are only two sites in all of France with spirals. They weren’t very popular yet in France during the Ice Age.

Another reason we don’t think the art was just doodling, is the amount of effort the people had to go to get the pigments they were using. Sometimes they were traveling up to 100 kilometers away from the cave site to collect the materials. They used mortars and pestles to grind up the pigments and mix them. There are also sites where they were using scaffolding. All of which suggests there was a fair amount of thought that went in to that site. They probably weren’t just hanging around there waiting for the bison to show up.

That said, while there are some areas of beautiful cave art that are very elaborate and seemed to require a lot of forethought and effort, other depictions are actually pretty bad. There is a whole variety of artistic ability being displayed.

In regards to doodling, there has actually been a lot of research on doodling. I was talking with a cognitive scientist who is studying MRIs of people as they doodle. Apparently doodling is culturally based. People only doodle things from their culture. So it’s unlikely they would accidentally tap into things they weren’t already familiar with.

On your website through the Bradshaw Foundation you talk about symbols you’ve recently added to your master list.

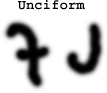

Yes, those are symbols from a pretty newly discovered cave. One of the symbols is an unciform — which is basically a hook shape.

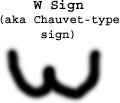

The other is what I call a “W” shape.

At one site, I’d seen a mammoth where they engraved this “W” shape as the tusks for the mammoth. Just because we don’t understand what these symbols mean, doesn’t mean the people of that era didn’t. Maybe we just aren’t recognizing them because we don’t have the context. It’s interesting that the “W” shape appears in that exact form on a mammoth, and it also appears by itself elsewhere. Mostly it appears by itself. So there’s the question, “Are we seeing the development of iconography?” You don’t need to draw the whole animal, necessarily, once everybody’s agreed that the tusks are representative of the mammoth. Drawing a whole mammoth is slow. It might be pretty, but it’s not very efficient if you want to communicate something.

I actually spent the whole fall term at the linguistics department at my university learning about the origins of writing systems. I wanted to know, before you have a fully formed writing system, what stages does a given system go through first? What are the first glimmers that you see? How do you figure out if signs do seem meaningful?

You said we really don’t know what the symbols mean, or why these people made this art. Do you have any theories?

When it comes to rock art in general at that age, I don’t think there’s a grand unifying theory. I don’t think there’s just one reason why they were doing the art.

I have a feeling that it breaks down much more like art does for us. We have everything from high art to graffiti to performance art. All of that brings in other areas of art they likely had, but that we can’t get at now: music and dance and potentially other things. I don’t think the cave art was created in a vacuum. I think it was in all likelihood created within the larger culture that existed at this time.

If I had to take a guess, I would say the art had varied purposes. The way some imagery is so public, some is private, the varying levels of quality … It just feels like there might have been different reasons why they were doing it in different cases, just as there is for our art today.

What’s the most interesting fact you’ve discovered through your research?

Certainly the one that intrigues me is that when I started my research, the general feeling was that the geometric signs started out being very crude and simplistic at the beginning of that time period. This kind of goes back to that old idea of people thinking that this type of art originated in Europe. Or alternatively, that it was an independent invention – wherever you went in the world, people just came up with this idea of doing it. That certainly is possible, but it just doesn’t seem very likely, considering the amount of crossover between the symbols in different geographic areas.

As I was collecting data, I assumed that I’d find this progression from crude markings to more sophisticated art. During the process, because I was looking at each site in such detail, I really didn’t know what the overall trends would look like until I was finished. When I ran my database, I suddenly realized, “Oh my god, 70 percent of the signs were already being used from the beginning.” This doesn’t fit the theory of a simple, crude start, and then becoming more elaborate, with more signs being used later on. They’re there right from the start, and they have a very strong presence.

I’ve just finished a journal article where I go back “before the beginning.” It looks at symbolic behavior in Africa prior to humans migrating outward. They have now found portable objects in Africa that go back 100,000 years. They’re still pretty simple at this point but what’s fascinating is that all of it is geometric. There is no figurative art yet, which actually makes sense to me. Traditionally people thought that the animals came first, and the abstract signs came second, but it now looks like the abstract markings were the first type of expression.

We know that all humans originated in Africa, and that people probably started leaving around 50 to 60,000 years ago. People were doing rock art from the time they arrived in Australia, too, and they were there by 40,000 years ago. So the question is, was this something that was already part of the cognitive toolkit of modern humans, before they left Africa? Was it something they’d already invented?

Long-term, I want the whole of Eurasia in my database. I want to look at migration routes and start tracking it backwards to learn if there is a basic group of signs that people already had at the beginning of the Ice Age.

You’ve talked at schools, libraries and even at a federal penitentiary, and always seem to have such eager listeners. Why do you think your work connects with people? It doesn’t seem like it’s very relevant to our lives today.

Well, my goal going into the prison was to try to make them forget they were in prison for a little bit. Could I take them outside of that, and could we talk about something that belongs to all of us?

I think that’s what it is, for all the audiences: it’s our common heritage as human beings that really gets people excited.

When did we become who we are? When did we become human? We live in a very symbolically mediated universe. That type of behavior and abstract thinking is very unique to humans. When did that start? When did we tap into the potential? We had the bodies and we had the brains, but when did we start using it? When did we start coming up with things that are totally non-utilitarian, like music?

We have 35,000 year-old flutes from the Ice Age. You can still play them. These things have absolutely no relevance to food, shelter, or heat. And yet, people were making them. So it’s an amazing glimpse into this entire mental world people had created for themselves — which is really what makes them us.

When you look at that time period, you see humans starting to move into all sorts of new regions and lanscapes. There was a lot of environmental change going on, and the things that got us through that were technological innovations. There was huge technological innovation going on at that point. We were inventing new tool types, inventing new ways to hunt, using group cooperation .… You know, we’re not the biggest, we’re not the strongest, but we work together. And communication — we communicate in a way that gives us so much strength and power when it comes to facing things we’ve never faced before.

One of the messages I always try to emphasize when I’m speaking with students is that you spend so many years reading books about people who have done cool things. It almost starts to feel like there’s nothing left to do. But there are lots of things that have never even been touched yet. Just keep your eyes and ears open. It can happen like it did for me: I wound up on the cover of New Scientist last year … and that was just for my Master’s research. Now here I am at TED!.

And for the record, I have to say, the penitentiary I went to — they were one of the best audiences I have ever had. They had the most intelligent questions. They were picking stuff up so fast, and were just completely engaged with the material .

You’re a big sci-fi fan. Like so many others, do you have any hypothesis about connections between extraterrestrials and early human art?

Well, I love astronomy. I’ve actually gotten to do the Drake equation, where you figure out how many planets per solar system, how many would have water … it’s a really cool equation. Considering the numbers, it just doesn’t make sense for there not to be intelligent life out there.

What I would say is that if there is intelligent life out there, I feel fairly certain that they are also using symbols of their own creation to communicate with each other.

There are many aspiring social entrepreneurs out there who are trying to take their passion and ideas to the next level. What is one piece of advice you would give to them based on your own experiences and successes? Learn more about how to become a great social entrepreneur from all of the TED Fellows on the Case Foundation’s Social Citizens blog.

To fund my research, I’ve often had to put it on hold to work – always in totally unrelated fields, like international banking — in order to make money to keep funding my degrees. I now have some grants, which is great, but I think that this could be a useful perspective for social entrepreneurs to keep in mind: while it’s really great for social entrepreneurs to work on things like global health and climate change — things that are important, and may seem more on the ground and in the present — I think it is equally important to continue to expand our body of knowledge as a species. This is part of what makes us so strong. If people stop paying attention to the more theoretical or esoteric research, I believe this could end up costing us in the long run. I think that research is what helps drive us forward. So I might suggest that social entrepreneurs could expand their vision of what working for the “social good” might include.

Comments (5)

Pingback: The music of sign language, a computer of water drops: 21 TED Fellows share ideas that swim against the tide | Lifespace connect

Pingback: Prehistoric Cave Drawings | SART 3480

Pingback: October 24 Colloquium: Genevieve von Petzinger on Upper Palaeolithic Art | UVicAnthro

Pingback: 9/13 Prehistoric Cave Art | Doherty for Western Civ

Pingback: Datenbank geometrischer Formen in prähistorischen Höhlenmalereien | kənˈspekt