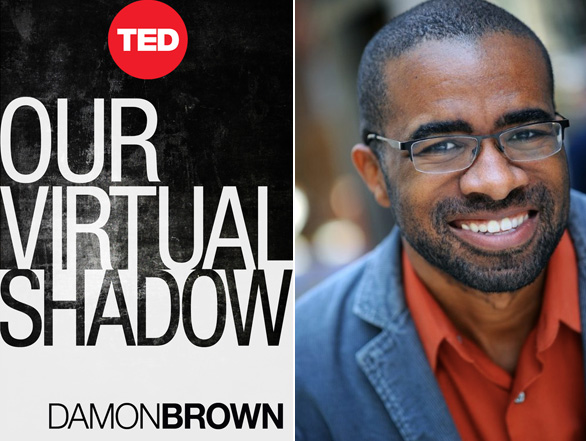

Are your endless tweets, status updates and Instagrams robbing you of enjoying what’s special about the moments you’re trying to share? Damon Brown fears they may. In the TED Book Our Virtual Shadow: Why We Are Obsessed With Documenting Our Lives Online, he lays out a compelling case for mindfully balancing your online presence with being present in the here and now.

Are your endless tweets, status updates and Instagrams robbing you of enjoying what’s special about the moments you’re trying to share? Damon Brown fears they may. In the TED Book Our Virtual Shadow: Why We Are Obsessed With Documenting Our Lives Online, he lays out a compelling case for mindfully balancing your online presence with being present in the here and now.

We caught up with Damon to get a better sense of why he feels that social media may have an asocial downside.

You argue that the electronic umbilical cord that connects us to others – Facebook, Twitter, etc — may, in fact, be strangling us. But you also say that this only happens if we let it. How so?

Technology has always been an issue for us, whether it was a child in the 1950s watching too much TV or a prehistoric caveman playing with a new discovery called fire. Like our ancestors, what we really need to do is find a smart way to integrate our newfound technology into our lives. The only difference now is that today’s tech is being discovered or created more rapidly than before. That, to me, is still no reason for us to throw up our hands and say our lives are suddenly spiraling out of our control.

Tech isn’t going away, either. In fact, it shouldn’t! But it should be balanced with old-school, classic ways of connecting. We shouldn’t believe that letter writing, phone calls, or even face-to-face meetings were rendered obsolete, just as email, texting, and Facebook messaging are not the ultimate ways for us to connect. I think saying technology is making us less attentive is a cop out. Now we should be focused on tech integration — not subservience.

This isn’t a new problem, as you suggest with your caveman example. We’ve struggled with these issues for thousands of years.

It is definitely not a new problem. In Our Virtual Shadow, I talk about Socrates having as much trouble with then-new technologies as we do with modern tech. Culturists seem to fall into two camps: Believing tech is our devil or that tech is our savior. Both are false, just as they were in the past.

In your book, you discuss the importance of ‘anchors of memory’, which are markers we use to remember a moment. How are those changing in our new tech-saturated age?

Anchors of memory are symbolic items we make to help remember a special time. It could be a photo of your grandfather coming back from the war or simply a Facebook check-in saying you are at a rock concert. You make them for something you deem important enough to note. Our anchors of memory today are becoming more virtual than physical, like our Instagrams and tweets, but they are just as valid as the physical photos and letters of yesteryear.

My concern is that we seem more and more focused on creating these anchors of memory – FourSquare check-ins, status updates, and so on. Unfortunately, the tools we use to create our modern anchors of memory, like the smartphone, require a level of multitasking that takes us away from the very experience we’re trying so hard to capture! It is the ultimate irony.

The computer scientist and author Jaron Lanier said he feels that social media makes us all feel blandly similar. Do you agree?

Lanier wrote the book, You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto. To paraphrase, he talked about social media flattening people into one big pile of mush. How can you represent the contradictions, dimensions and ideas of any one person in a simplified social media profile? You can’t. It’s like those business commercials where they promise to not treat you like a number. In my interpretation, Lanier said that social media’s architecture and format essentially turned everyone into another number. It is rubbing all the rough edges off of everyone’s personality and making them fit into a fixed box. These varied people, then, turn into a big, non-descript pile of mush.

In Our Virtual Shadow, I argue that Lanier’s theory not only applies to social media, but also to how we interpret and receive news on the Internet. For instance, I can tweet something right now to my couple of thousand followers and, because they trust me, they will retweet it to their followers, and so on. It could be shared to so many degrees that people don’t even know that it came from me. Is what I said true? There is no way to prove the voracity and, at a certain point, it’s not going to matter to the reader. It will just be accepted as truth because someone they trusted shared it. That “news” has been scrubbed of all its edges – and its accountability – and it just becomes something someone heard on the ‘net.

There’s also a lot of good that social media brings us, though, on a personal and professional side.

There is definitely much good that comes from social media. I’m a huge Twitter fan and even cofounded my own social media app, Quote UnQuote. I think we just need to ask the same question we do with other activities: Is this affecting my quality of life? For instance, if you’re spending quality time with your family and you feel the urge to pull out your smartphone and do a Facebook post about spending quality time with your family, consider if it is really necessary at that very moment.

Social media has the ability to make things feel more urgent than they actually are. We jump from attention-stealing activity to attention-stealing activity and, before we know it, time has flown by. The point of the book is that we use these potentially-distracting tools to capture a moment, but they are just time consuming enough to significantly pull us out of the moment. We will never again, say, watch our toddler walk for the first time or have a virgin meal at the famed The French Laundry. Facebook, Twitter, and the rest of the networks, however, will be right there waiting for us whenever we want to visit. Life disappears, social media doesn’t — though we are often operating based on the opposite assumption.

How do we balance out the good with the bad? How do we become more present?

The best solution is to remember that there will always be a new social media tool, a new gadget, or a new technology that will ask for our attention, but there will never be a tool that replaces our memories when we allow ourselves to be fully present. There are several recent studies that say not only can’t we multitask successfully, but that multitasking prevents us from remembering life experiences as well as we could. The next time you are having a breath-taking experience, try not to do a Pavlovian reach for the smartphone. Researching this book made me really question my own social media habits, and, if you put the smartphone aside for a bit, I think you’d be surprised at what you recall — what you notice — and even what you feel.

“Our Virtual Shadow” is available for the Kindle, Nook, or through the iBookstore. Or download the TED Books app for your iPad or iPhone. Read more »

Comments (10)

Pingback: First Tutorial – Convergent media

Pingback: “There will always be a new social media tool, a new gadget, or a new technology that will ask for our attention, but there will never be a tool that replaces our memories when we allow ourselves to be fully present.” | Official Nextt Blog

Pingback: Does social media stop us living in the moment? | The Cyber Psyche

Pingback: Nextt Blog | The Nextt Manifesto – Get Busy Living in the Real World

Pingback: Does documenting your life online keep you from actually living it … « Mashir

Pingback: The asocial side of social media: TED Book author … – TED Blog « Mashir

Pingback: Would Seinfeld like Facebook? | Random Thoughts