Astrobiologist and geologist Louisa Preston looks for analogues to possible life on Mars in the most extreme environments on Earth. Now she’s also considering how humans might someday make a home on the red planet, and is raising funds on Kickstarter in support of AstroGardening – an educational exhibit designed to explore how we might someday grow food on Mars.

Tell us about your Kickstarter campaign for the AstroGardening project.

It’s based around the idea of Mars gardening. If humans want to go to Mars, how would we live when we got there? What would we need, and what would it look like? With the advancement of space exploration, we’re finding that ideas like this are actually becoming a lot more real – not quite science fiction.

The exhibit, which will be hosted in a number of planetariums and museums in the UK, will be inside a plastic geodesic dome, within which is a beautiful, peaceful garden full of different types of plants, fruits, vegetables and flowers. The soil will be red, just like Mars. There will be signs and information everywhere where people can learn about the different plants, how they might grow on Mars, and the various ways we need to develop tools so we can garden on Mars. Mars is frozen, so we need to be able to extract water and keep plants warm, for instance.

And there will be a rover — the first-ever rover designed solely for gardening. It will be automated to be planting a garden at the end of the exhibit, so people can see it in action.

My project partner, installation designer, maker and guerilla gardener Vanessa Harden, and I are designing and building the rover right now. The Kickstarter funds will be used to build the rover, the exhibit itself — plants, soil, the dome — and so on. Most of the venues have agreed to house the exhibit out of kind, for education purposes, so we’re not paying a fee, and it’ll be free for anyone to come and visit it.

Video above: Introducing the AstroGardening project — and the automated gardening rover.

Does this mean that plants that grow on Earth could be transplanted directly to such an environment?

Yes, absolutely. There have been a number of studies that show that if you plant things like asparagus or potato or sweet potato or different types of grains in soil that’s exactly the same as on Mars, they will grow as long as they have water and sunlight and things that plants need. I think one experiment actually showed that you could grow marigolds in ground-up meteorites, and meteorites from Mars. So we know the planet’s soil will allow it. We just need to create the environment.

The exhibit will explain this to people. It will also teach about the conditions on Mars, how plants grow, what they need, why it’s hard for life to grow on Mars, what therefore makes the Earth so special — and from there why it’s so important for us to protect the environment.

I wasn’t going to lead it on to terraforming, but actually I was speaking to my 10-year-old cousin about it, and he asked, “Well what about if we could change Mars to be like Earth?” Terraforming is a really interesting topic, and sounds very much like science fiction, but there are people looking into it. So hopefully the exhibit will address that point and allow people to ask questions, and we’ll be able to provide the answers about how it might be done, and what the ethics are around whether we should be allowed to change another planet to suit us.

The whole thing came out of a desire to get the public involved in understanding that we’re not very far away from gardening in space becoming a reality — actually being able to garden and set up colonies and civilizations on other worlds — and how it might happen. So we came up with an exhibit that the public can be involved in and not only looks beautiful, but is scientifically relevant and accurate.

How does this dovetail with your work looking for analogue Mars environments on Earth?

It works brilliantly. I look for environments on the Earth that mimic Mars, and I study how life can grow there. In the past, I’ve studied how microorganisms survive in these environments. Are these places really hot, really cold, really acidic, really dry? So it’s a natural step for me to then start thinking about how you might grow plants or how we as humans might survive in these areas, too.

I grew up watching TV shows and films about humans and aliens living on other worlds and I kept thinking, Well how would we live there? These worlds look completely different from ours; how would we survive? And now I’m finally in a position to actually be able to think about this question and use science to answer it.

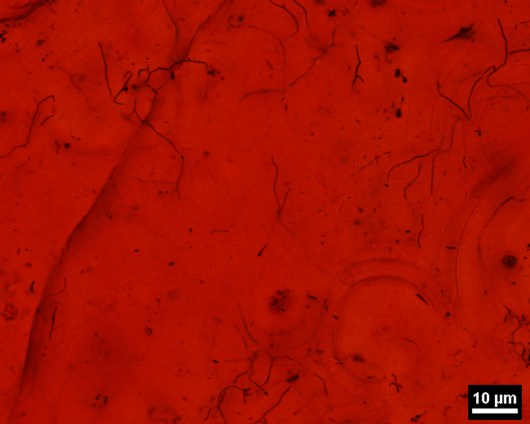

Rio Tinto in southwestern Spain is a wonderful natural laboratory where we can study acidophiles (acid-loving bacteria) living in the iron-rich waters today (above), and study fossils of their ancestors that have been preserved for up to 2 million years within iron-rich rocks along the river bank (below).

How did you get into the field of astrobiology?

I was following along a geology career, studying mining, looking at all the different types of minerals that the Earth produces and how we might utilize those as a society, and I met a PhD student who was working on life preserved within rocks in Antarctica. Up until that point I didn’t completely realize or understand that you could actually look for life on other planets as a job — that it was actually a facet of what I was doing. So I did my PhD on a combination of looking at mineral deposits like I’d been studying before, but trying to incorporate the idea of life around these rocks and then life on Mars — to try and merge the two. And I was hooked. I knew that all the rest of the work that I would do from then on would all be geared towards trying to identify and find life on other planets.

Now my main work is looking at environments on Earth that mimic those on Mars. I look at places such as Antarctica, which is the coldest, driest desert on the Earth and is actually the most Mars-like environment we have on Earth. I look at areas in Spain such as Rio Tinto, and I work at impact craters. I’m going to Iceland this summer to do more work on volcanoes and hot springs. What all these environments have in common is that they are places where life lives at very extreme limits. It’s either very, very hot or very cold — places where humans couldn’t survive without lots of help, but some organisms can live perfectly happily.

I try and figure out how they’re able to survive there, what adaptations they have that allow them to survive there. And I study nearby rocks as well, because as these are forming they trap the organisms in them. When I open up these rocks, I can see fossilized life, similar to the type of life we think we might find on Mars. We won’t necessarily see life scuttling around on the surface of Mars, but we might be able to break into a rock, open it, and see fossilized life inside. I look for DNA and proteins, and try to understand how these fossils are formed and identify organic molecules that indicate this fossil was once definitely an organism, not just, say, a wiggly pattern.

You’re working with Senior Fellow Angelo Vermeulen on the HI-SEAS Mars simulation project, where they are investigating how humans might be able to cook their own food on Mars, and his own research on this mission about growing food on Mars is very similar to yours. Did you arrange this together?

Actually, I didn’t get involved in HI-SEAS through Angelo. I do a lot of analogue mission work myself — I was a flight director for a Canadian Space Agency analogue mission. So when the call came out that they were asking for people to be involved in HI-SEAS and to support the mission, I got contacted just through my prior experience.

Angelo didn’t even find out I was supporting the mission until he was actually in the simulation. It was a wonderful moment: we had a kick-off meeting on Skype for all the mission crew to meet the astronauts, including Angelo. When we went around and introduced ourselves, I just said, “Hi. My name is Louisa Preston. I’m an astrobiologist based in London.” All I heard in the other room was, “Louisa??” Now we’re communicating, him on Mars and myself here — and I’m trying to help him with his research as he goes through the mission. It’s really good fun. Every so often he’ll send us a call asking if anyone’s seen any good papers recently or research we might be able to incorporate.

At the moment, I’m studying something that’s a little bit different from what he’s doing. He’s looking at plants that basically don’t need any kind of pollination. They don’t need bees; they don’t need anything to help them reproduce. They just naturally do it. I’m asking, “How would we actually get bees — or use something like bees — on Mars to pollinate plants, and how would we breed them?” So we’re removed at the moment in those areas, but we’re looking to try and join our studies eventually, so it could be interesting. Angelo and I had already been looking for a reason and a way to work together, and this was a perfect opportunity.

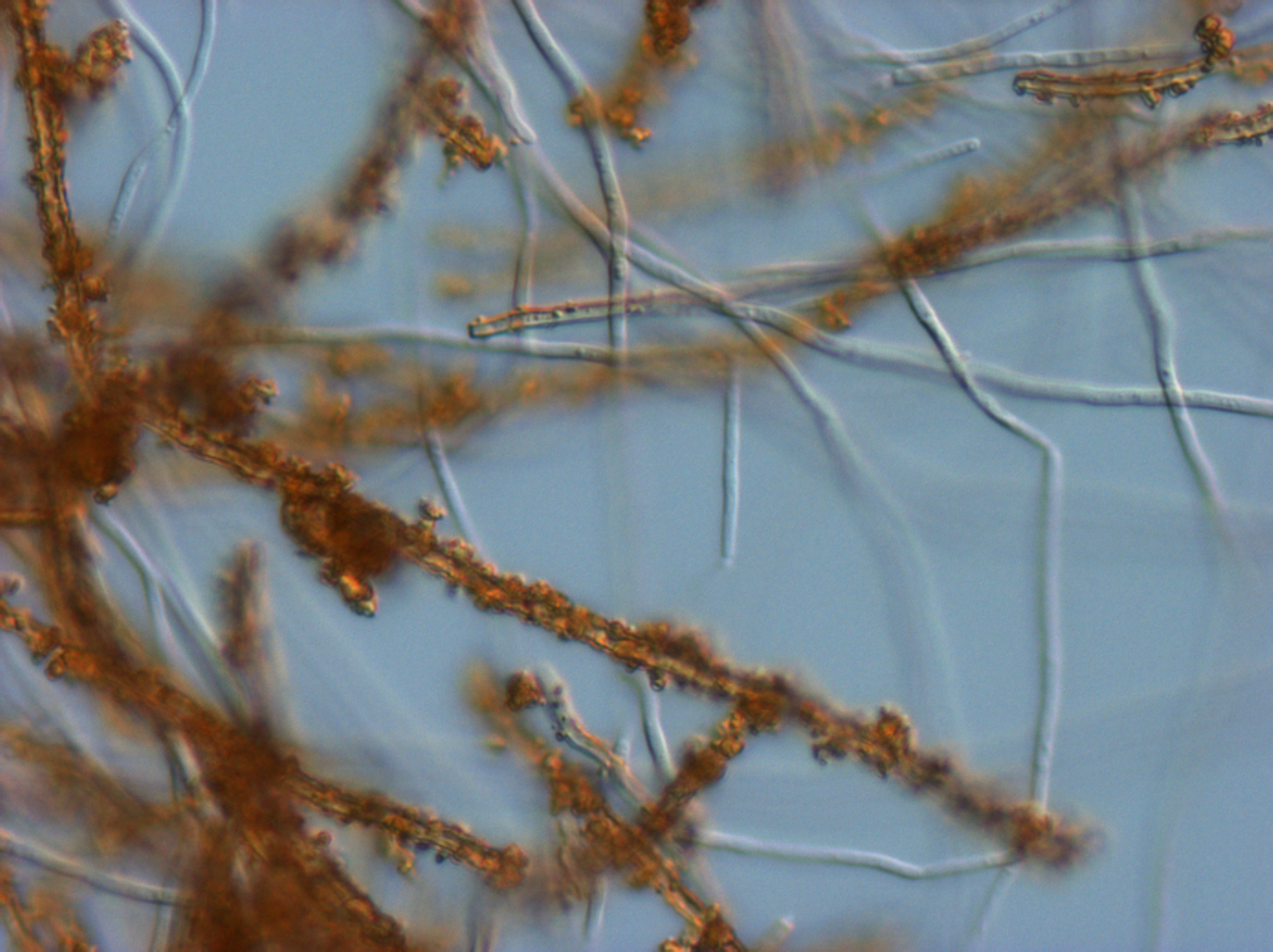

Testing the temperature and acidity of hot springs in Iceland, looking for life thriving within this extreme environment.

What does it mean to be a flight director on an analogue mission, and why would a astrobiologist need to have such an experience? You’re not actually flying anywhere…

Our analogue mission was based in Canada, and it was to send a team to the Canadian high arctic where they were going to study an impact crater. When you have a mission, whether on Mars or on Earth, you have a team that goes into the field, or to Mars, and a mission control. Leading mission control is the flight director who basically manages the team. And that was my job.

There are a number of things you get from these scenarios. The first one is management experience, which doesn’t sound particularly exciting. But in these teams you have engineers, scientists, computational experts, field specialists, medics, psychologists, and a number of different people working together. In our field, if you’re going to stay in space science and you want to work in missions and help extend our knowledge of the solar system, you need to be able to work in a very dynamic team full of extremely different people from disparate backgrounds, and who therefore all think very differently.

There’s a very common clash between scientists and engineers, for example. The scientists want to go to this rock, say, to look at a cool bug. The engineer says, “Well I don’t know how to get you there.” And the scientist says, “Well I want to go there.” There’s always this clash, but it’s a friendly clash with a joint goal. You need the skills to be able to negotiate through this. So to be part the larger picture and to work in these situations and planning missions to other planets it’s an invaluable experience. It’s really good fun as well.

What has your TED experience been like so far?

The one thing about the TED conference is I think everyone spends an entire week with imposter syndrome, because you go there very confident in what you do and very excited to tell everybody about it — then you speak to even one single person and hear what they do and think, “Oh, that’s so much cooler and more interesting than what i do.” The Fellows community is very active; I’m talking with and potentially working with three Fellows at the moment on a number of different projects, which will be really exciting. And a lot of really great publicity has come from being associated with TED, even in the UK where it might not be as well known as it is in America.

I’m also now one of the directors of TEDxLondon, which is happening in July. Its theme is visions of the future, which is not at all in my area, but that means I’ve actually spent a number of weeks speaking with architects and designers and science-fiction writers about their visions of the future, which is absolutely fascinating.

Comments (6)

Pingback: More to life than DNA: Fellows Friday with Sheref Mansy | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: More to life than DNA: Fellows Friday with Sheref Mansy | Best Science News

Pingback: More to life than DNA: Fellows Friday with Sheref Mansy | Krantenkoppen Tech

Pingback: MAGIC VIDEO HUB | More to life than DNA: Fellows Friday with Sheref Mansy

Pingback: Astrogardening Update | Dr Louisa Preston

Pingback: The guerilla astrogardener: Fellows Friday with Louisa Preston | TEDFellows Blog