Dan Gilbert gave his first TED Talk in February 2004; The surprising science of happiness was one of the first we ever published, in September 2006. Here, the Harvard psychologist reminisces about the impact of TED, shares some suggestions of useful further reading — and owns up to some mistakes.

Dan Gilbert gave his first TED Talk in February 2004; The surprising science of happiness was one of the first we ever published, in September 2006. Here, the Harvard psychologist reminisces about the impact of TED, shares some suggestions of useful further reading — and owns up to some mistakes.

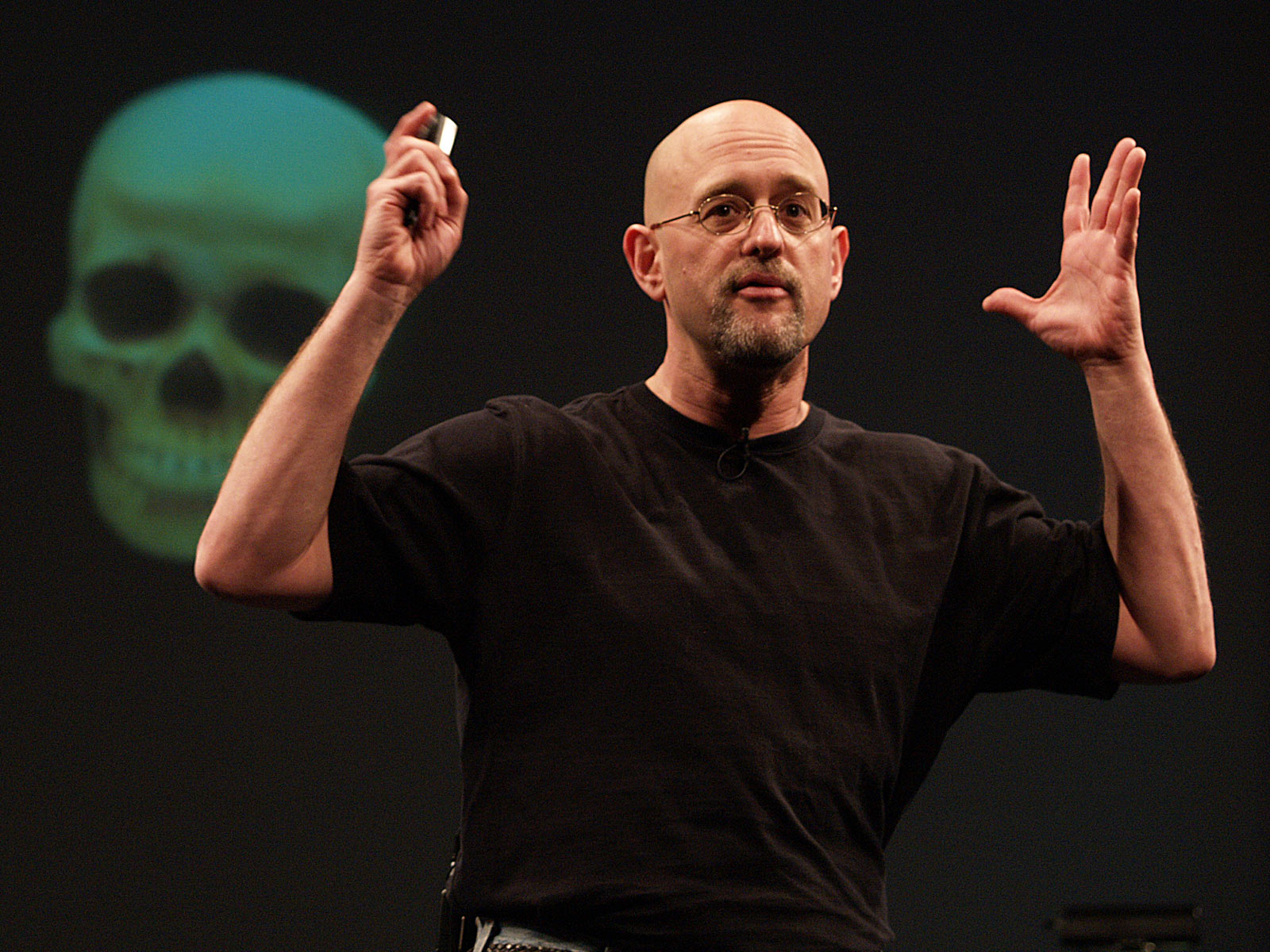

When I gave this talk in 2004, the idea that videos might someday be “posted on the internet” seemed rather remote. There was no Netflix or YouTube, and indeed, it would be two years before the first TED Talk was put online. So I thought I was speaking to a small group of people who’d come to a relatively unknown conference in Monterey, California, and had I realized that ten years later more than 8 million people would have heard what I said that day, I would have (a) rehearsed and (b) dressed better.

That’s a lie. I never dress better. But I would have rehearsed. Back then, TED talks were considerably less important events and therefore a lot more improvisational, so I just grabbed some PowerPoint slides from previous lectures, rearranged them on the airplane to California, and then took the stage and winged it. I had no idea that on that day I was delivering the most important lecture of my life.

Mea Maxima Culpa

When you wing it, you make mistakes; and when millions of people watch you wing it, several hundred thousand of them will notice. There are at least three mistakes in this talk, and I know it because I’ve been receiving (and sheepishly replying to) emails about them for nearly ten years. I’m grateful to have the opportunity to correct them.

Mistake 1. Lottery Winners & Paraplegics: The first mistake occurred when I misstated the facts about the 1978 study by Brickman, Coates and Janoff-Bulman on lottery winners and paraplegics.

At 2:54 I said, “… a year after losing the use of their legs, and a year after winning the lotto, lottery winners and paraplegics are equally happy with their lives.” In fact, the two groups were not equally happy: Although the lottery winners (M=4.00) were no happier than controls (M=3.82), both lottery winner and controls were slightly happier than paraplegics (M=2.96).

So why has this study become the poster child for the concept of hedonic adaptation? First, most of us would expect lottery winners to be much happier than controls, and they weren’t. Second, most of us would expect paraplegics to be wildly less happy than either controls or lottery winners, and in fact they were only slightly less happy (though it is admittedly difficult to interpret numerical differences on rating scales like the ones used in this study). As the authors of the paper noted, “In general, lottery winners rated winning the lottery as a highly positive event, and paraplegics rated their accident as a highly negative event, though neither outcome was rated as extremely as might have been expected.” Almost 40 years later, I suspect that most psychologists would agree that this study produced rather weak and inconclusive findings, but that the point it made about the unanticipated power of hedonic adaptation has now been confirmed by many more powerful and methodologically superior studies. You can read the original study here.

Mistake 2. The Case of Moreese Bickham: The second mistake occurred when I told the story of Moreese Bickham. At 6:18 I said, “He spent 37 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary for a crime he didn’t commit. He was ultimately exonerated, at the age of 78, through DNA evidence.” First, whether Mr. Bickham did or did not commit the crime is debatable. His attorney tells me that he believes Mr. Bickham was innocent, the state evidently believed otherwise, and I am no judge. Second, Mr. Bickham was not exonerated on the basis of DNA evidence, but rather, was released for good behavior after serving half his sentence.

How I managed to mangle these facts is something I still scratch my head about. Bad notes? Bad sources? Demonic possession? Sorry, I just don’t remember. But while I got these ancillary facts wrong, I got the key facts right: Mr. Bickham did spend 37 years in prison, he did utter those words upon his release, and he was (and apparently still is) much happier than most of us would expect ourselves to be in such circumstances. You can read about him here.

Mistake 3. The Irreversible Condition: The third mistake was a slip of the tongue that led me to say precisely the opposite of what I meant. At 18:02 I said, “… because the irreversible condition is not conducive to the synthesis of happiness.” Of course I meant to say reversible, not irreversible, and the transcript of the talk contains the correct word. I hope this slip didn’t stop anyone from getting married.

Digging Deeper

I mentioned two of my own studies in my talk, and people often write to ask where they can read about them. The study of the amnesiacs who were shown the Monet prints was done in collaboration with Matt Lieberman, Kevin Oschner, and Dan Schacter, was published in Psychological Science, and can be found here. The study of Harvard students who took a photography course was done in collaboration with Jane Ebert, was published in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, and can be found here. Pretty much everything else I’ve ever thought, said, written, felt, done, wondered, cooked, smoked or eaten can be found here.

Coda

Giving this talk taught me something I hadn’t known: normal people are interested in the same things I am! Until that day, I’d always thought that psychologists did experiments for each other and occasionally subjected undergraduates to them in class. What I discovered at TED in 2004 was that I could tell a story about human psychology to regular folks and some of them would actually want to hear it. Who knew? I’d been a professor for 20 years, but that was the first time it had ever occurred to me that a classroom can be roughly the size of the world.

I left TED determined to devote a portion of my professional life to telling people about exciting discoveries in the behavioral sciences. So I started writing essays for the New York Times, I wrote a popular book called Stumbling on Happiness, I made a PBS television series called This Emotional Life, and I even appeared in a Super Bowl commercial to try to remind people to plan for their futures. I don’t know what I’ll do next –another book, a feature film, a rock opera? Whatever it is, you can almost certainly blame it on TED.

Comments (71)

Pingback: TED Talk: Din hjerne er designet til at gøre dig lykkelig | Sundhed og Sygdom blog

Pingback: Dan Gilbert: “The Surprising Science of Happiness” | ABIGAIL NOLDY

Pingback: The Science of Happiness |

Pingback: The Science of Happiness | MSU_GradLife

Pingback: Futureseek Daily Link Review; 12 April 2014 | Futureseek Link Digest