Drew Curtis is running for governor of Kentucky, to see if he can end “the vicious cycle of influence money in politics.” His running mate is his wife, Heather Curtis, COO of Fark.

Drew Curtis is not a politician. The curator of Fark.com, the legendary online community of news jokes and funny Photoshops, he proudly proclaims this fact on homepage of his latest website. This declaration is only surprising because, just a few inches above, the intention of the website is revealed: “Drew Curtis for Governor.”

See, politics have long irked Curtis. On Fark, he found himself having the same conversations over and over again that so many of us have — why does the political system seem so broken? why is heading to the polls always a choice between two mediocre options? One night in 2010, Curtis even deleted the “politics” tab on Fark, because the arguments there just felt so pointless and interminable.

Then last year, as he wrote on the site, “A friend challenged me: People who are capable of running for office and winning have no right to complain about the system when they have the ability to change it.”

Which is why Curtis — who gave a hilarious TED Talk three years ago on how to beat a patent troll — decided that he was going to run for the governor of Kentucky with his wife, Heather Curtis, Fark’s COO, as his running mate.

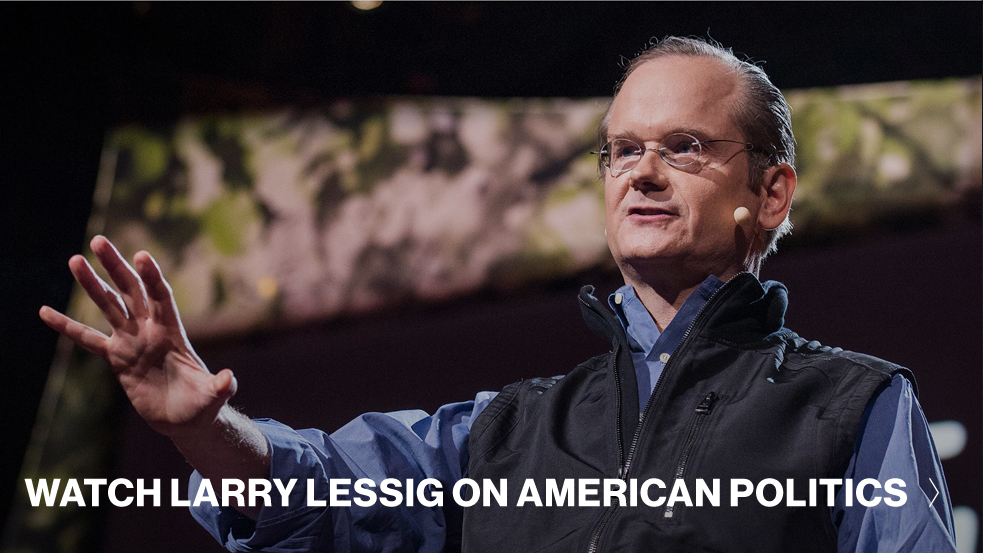

Curtis’ ambition isn’t just the governor’s mansion. No, he wants to take on a political system that makes politicians beholden to large donors, at the expense of the people they govern. It’s a mission sparked by another TED Talk, from political activist Larry Lessig — and Curtis hopes that his campaign will become a blueprint for others who want to try this. We called Curtis at his home in Kentucky to find out more.

What inspired you to run for governor?

It was a number of things: mostly a general dislike for the type of candidates that we’ve gotten, and a wondering if there are better ways to do this. I’m a pattern guy, and one of the patterns I realized was: political parties are really just 19th-century social networks. In a pre-technology society, how else would anybody find out about you if you didn’t have the backing of an organization that could get the word out? But the rules have changed. The parties and the media are not the gatekeepers of influence anymore.

Another piece that came into play: Larry Lessig’s talk on the influence of money on politics. I was there when he gave the talk and I just hadn’t really thought about the the fact that there are so few people donating so much money [to political campaigns] before. Lessig nailed it. And now we have issues like net neutrality — which should not be a partisan issue at all — becoming highly polarized, mainly because telecoms needed to buy the legislature. Watching that shift happen bothered me. What chance is there that we are going to have politicians that can take a good, hard look at legislation and make a research- or data-driven decision? The way it works now is: here’s a bill, check my donor list, vote accordingly. Whether it’s good for the public never even comes into the conversation.

I talked to [Larry] briefly after his talk, and have spoken with him a couple of times since. I thought it was interesting that he wasn’t considering [a run] at a state level. One of the reasons why I’m shooting for governor is because as a legislator who is anti-influence money, you’re just one person out of however many. But if you are an executive who is anti-influence money, you can shut everything down immediately.

What would data-driven decisions look like in practice?

The way you do it is: Step one, recognize your bias, and put that aside for a second. Step two, examine both sides of the issue, and see what data is available. Step three, look at who put out the data and pick out the bad math. Take a look at every issue. It’s unlikely that there are going to be obvious solutions. But what I would do is look around at other states and say, “Hey, has anybody got anything that worked on public/private partnerships for planning infrastructure?” We don’t have to come up with things in a vacuum. Rather than conjecture about what would be best, let’s look around and see what’s worked.

Now, I know that this is a really weird pitch. Political junkies don’t know how to deal with this framework at all.

You’ve said that you wanted to retool the executive branch to better interface with customers. What are some ways that could work?

I’ll give you an example — a friend of mine was recently talking about retail theory. It’s insane: when they send out clothes, it comes with a packing list that says exactly what order to stack up the stuff when you unpack it. They’ve figured out, based on algorithms, how to predict demand. I was thinking: how you could apply that to government? You could start predicting a really busy day at the DMV, and then staff up or down accordingly.

Another example: Instead of having to go down and get my car registration renewed with cash or a check, let’s have the government hold a credit card on file that they could just run every year and mail me the registration. Then the 10% of people who don’t have access to technology that allows them to do that will get better assistance when they show up, because the lines will be a lot shorter.

We could go down the row with these little, tiny, easy ideas. Another one: I want to talk to companies that have franchises. They use algorithms to determine where they’re going to put their next restaurant, and they are not just looking at right now but how things will be in five years. I would like to ask, “What are you seeing? Who just missed the cut? Is there something the government could do?” If they have the data, they might share it. We do not have to reinvent the wheel.

I’m so tired of politicians using air quotes when they use the word internet. This technology is 30 years old now — it’s so ubiquitous, my kids think of it as air. We have a generation like that coming up, and we need to start thinking about improving the little things. I would like to make 10,000 small changes. That will make a huge difference in the way that people interface with the government.

How long have you lived in Kentucky?

I was born and raised here. I went away to college, but then I ended up taking a summer job here that lasted six months. Then I started my business.

The nice thing about being in Kentucky is that we don’t have to be number one — for the most part, we’re 45th in everything, so there’s lots of room for improvement.

Kentucky is a state that has a lot of stereotypes attached to it. What would you like to show the country about your state?

It’s more progressive than you think. Lexington just re-elected an openly gay mayor, and that issue was not even mentioned once by either of his opponents. I describe the people here as ‘accidentally progressive.’ People will say they’re conservative, but when you talk to them, they more or less aren’t. I’m not saying that they’re super liberal, but you can tell somebody from Kentucky, “Here’s a thing we should try — it makes sense.” And they want to see what happens.

I’ve been advocating for Kentucky in Silicon Valley for years now. We have an abundance of engineering talent here that would love to get involved in startups. I’ve been telling people to open up satellite offices here — we’ve got mountains, nature, a low cost of living. My venture capitalist and TED friends are more or less convinced, so it just seems like success waiting to happen.

How has being part of the TED community influenced your decision to run for office?

It made me think I was capable of doing this. Being at TED, around all these amazing people, you just sort of think, “Why not?” There are all these people who do awesome things for a living, and suddenly I can call out to this network and ask, “Hey, does anybody know anything about _____?” It connects you to thought leaders who have no political axe to grind and really just want to solve problems.

If you’re elected Governor, anything you would change about patent law?

Oh, yeah—definitely.

What will make Heather Curtis an excellent lieutenant governor?

To give you an anecdotal answer, I have a friend who I met at TED who has been very much against [my running] the entire year — until he found out that Heather was going to be my lieutenant governor. Then he was like, “Wow, actually this could work.”

Everybody who knows us gets it. She’s been Fark’s COO for 16 years, and we work in tandem on strategy and execution. She is detail and ops, so it just made sense for her to run with me, considering that she was likely to be doing that job behind the scenes anyhow. So far, she’s been great in making sure that I’m on track and staying focused. We’re just a really good two-person team.

Tell us more about your idea of building a blueprint that other people can use to run for office. How are you making this replicable?

I’m going to do campaign speeches, and keep updating people on where we’re at. Surprisingly, once you’ve filed, it’s rather smooth. But before you get to that stage, there are lock-outs at many levels. For example, I have to produce 5,000 signatures by August — Democrats and Republicans in the race don’t have to do that.

Then there’s a lock-out on the media level. A lot of people have said to me, “I’ve thought about [running], but I have too many skeletons in my closet.” When I ask them what they are, nine times out of ten it’s not a showstopper. It’ll be, “Oh, there are photos of me in my fraternity.” Everybody has something like that. We need to redefine what an actual skeleton in the closet is, because I think this concept is being used as a lock-out tool to scare people from getting involved unless they’ve come through the traditional channels.

But the biggest lock-out I’m going to have to figure out is: how do you fundraise for a campaign that is burning all chance of getting influence money? I don’t want influence money because I don’t want to be influenced — but that’s 90% of the money a campaign raises. How do you navigate around that?

If you told your teenage self that you were running for governor, what would he have said?

I just had my 20th high school reunion, and everybody there said they were not surprised. So I don’t know if my teenage self would’ve predicted it, but my high school classmates would have. My teenage self would probably wonder how I reached this decision, because it wasn’t something I wanted to do all along. It’s still only something I only want to do if I can do it my way.

I got a long, unsolicited advice note from somebody in politics recently, and there were so many bullet points that I was just slapping my forehead. The first one was: never admit you don’t know the answer to a question. That rubs me the wrong way, because I don’t know the answer to a lot of questions.

I’m still out there in the theory-space right now. I’m planning on doing this completely against the rule book. So what exactly is it that I should be doing instead? I’ve got ideas, but if anybody who reads this has thoughts, I would love to hear them.

Comments (5)