Interactive Fellows Friday Feature!

Join the conversation by answering Fellows’ weekly questions via Facebook. This week, Gerry asks:

What is it about your favorite video games or computer programs that make them intuitive and easy to use?

Click here to respond!

There are several electronic medical records systems already in existence. Why not just use one of them?

Healthcare in a developing world setting is different than the developed world for a variety of reasons. For example, the ratio of patients to doctors in the US is about 400 to one. In Malawi, it’s about 50,000 to one. So, if you’re lucky enough to actually get to see a doctor as a patient in Malawi, the time you spend with that doctor is about three to five minutes. There’s no time for doctors to have some computer in front of them that’s going to take a lot of work to document and require a lot of learning to become proficient in.

Everything we develop at Baobab Health is based on the assumption that the user has no computer experience, no keyboarding skills, and that they’ve got three minutes with their patient. And they’re not going to do anything that they wouldn’t normally have done on paper anyway.

Big electronic medical record systems like Epic’s, or even the open-source VistA, are built for Western healthcare systems, and are designed to address specific needs. Interestingly, the development of electronic medical record systems in the West has largely been driven by billing and reimbursement, and medical-legal issues. Baobab, on the other hand, focuses primarily on creating systems that address the user’s value proposition, and put patient management first.

What specific characteristics are unique about Baobab’s product?

I always talk about the work we’ve done not as a system or a product, but a philosophy. The philosophy is this notion of point of care. The idea is that you have the technology in the room with the doctor and the patient at the same time.

Using point-of-care is like having another colleague in the room with you that you can interact with. It dynamically reconfigures to guide health care workers through the process. Think of a GPS that dynamically reconfigures as you make different turns, versus directions that are printed out on paper. If you make a wrong turn while reading those directions, you’re out of luck. That’s the difference between point-of-care and paper documentation in the healthcare setting.

Point of care is considered the optimal solution in Western medicine. But even in the West, a very small percentage of hospitals and doctors’ offices have been able to implement point-of-care systems because of challenges around workflow.

We looked at a point-of-care solution in the developing world setting, and we’ve come up with a number of secret weapons. One is to really optimize the usability of the system. If you look at my nine-year-old son’s Nintendo DS, the usability of that video game product is super high.

We’ve also removed the complexity that you might see in a traditional electronic medical record, breaking the process down into logical steps. It’s what we call a Wizard-type interface. It’s just like buying something online … select your items, choose your shipping, enter the payment details, and you’re done.

Another secret weapon, appliance-model computing, is the idea that you give them a computer that does exactly what they need, and nothing more, and it’s optimized for that function. We don’t put other stuff in, because when you have other stuff and it breaks, then people say “The computer’s broken, and I can’t use the computer.” This happens even if it’s something not necessary for the job, like speakers. Appliance-model computing also reduces the chance that people will use the computer for something besides providing primary care.

One of your most celebrated adaptations is the touch-screen interface. Why is this so important?

The speed with which you can reach proficiency with the touch screen is much higher than with keyboarding skills. We design systems that use pick-lists, reducing the need to type as much as possible. Where text is required, we use an onscreen keyboard. We give the option for the user to use the QWERTY keyboard, but they can also just have the keyboard from A to Z, and they learn much faster that way.

Being able to reach proficiency quickly is very important. It’s much more important when you have a high turnover of staff, or you have staff who don’t regularly work in your clinic, which is a very common setting in a developing country.

Unlike in the States, where doctors are typically high earners, in many developing countries, the healthcare salaries are appallingly low. In Malawi, at the end of the month, many health care workers are coming in to work, knowing they don’t have food at home for their kids that night, and they spent their salary that month. People will change jobs overnight just to increase their salary by a small amount. And we’re losing health care professionals to HIV, too. In Malawi the HIV prevalence rate is 14 percent. People are dying, and that includes healthcare workers.

So we have a very high turnover of staff for a variety of reasons. If it takes six months for a person to become proficient to use this electronic medical record, it’s not going to work. With the Baobab system, you can show it to a person twice, and they’ll be up to speed in a week.

As a British-Canadian, how did you get involved in computerizing Malawian health care systems?

I was living in Victoria, and had worked with technology and computers, and had been an avionics technician. I decided I wanted to try something different, so I applied for Voluntary Service Overseas in 1996. I was assigned to Malawi, where I met my future wife, who was a Peace Corps doctor there.

I was recruited to work in the Ministry of Health to help process health statistics from health centers. There were about 700 different hospitals, clinics and health centers in the country. They were supposed to send in monthly reports about how many people were sick, different diseases, morbidity and mortality. Our office was supposed to collate all that and produce this annual report.

I worked for about a year on that in Malawi. But I really saw a lot of problems with the system. The data was very incomplete and inaccurate. It just made me wonder, “Is there any real value in producing these reports if you know that they are inherently flawed?”

Toward the end of my first year in Malawi, I went to the Ministry of Health and said, “I don’t think I should be here in this office. I think I should be in a hospital where this data is collected and really see why this data is not being captured properly. Because unless we can address the root causes of this, we’re never going to have accurate reports.”

I followed my wife to Pittsburgh and got a master’s in medical informatics and started a PhD. In 2000, I decided I wanted to go back to Malawi and see what was going on, and what had changed. I wanted to find ways to apply what I’d learned –- how electronic medical records systems can improve health care delivery — in a developing world setting.

In the developing world, having a reliable power supply can be a big challenge. How does that affect Baobab’s work?

On average, Malawi has one day a week that businesses – including hospitals – are unable to operate because they don’t have electricity. There are generators for vital hospital services, but they don’t have the ability to provide power for very long.

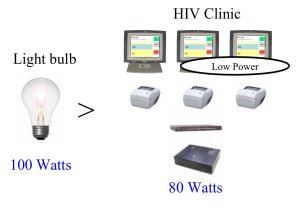

When we first got started building our touchscreen systems, we ended up buying these obsolete Internet appliances on Ebay, and in the end had a large donation of them. We converted them into touchscreens. We were just really lucky that that particular device had very, very low power consumption. We could deploy three touchscreen computers, three label printers, a network switch and a server, and the combined power consumption of that is less than a 100-watt light bulb. So we get multi-day power back-up. For point-of-care systems, it’s essential to have power when the doctor’s in the room with the patient.

This of course leads to great cost savings. Having low-power technology is also important for sites where there is no grid, and you want to use a renewable energy solution. The touchscreen uses a quarter of the power of its equivalent desktop computer, which means you only need to invest in one quarter of the amount solar panels or windmills you otherwise would.

In Malawi, there are four large central hospitals and 20-something district hospitals. But underneath that, there’s 397 health centers, and that’s where the majority of healthcare really takes place. Many of these are entirely off the electrical grid. I think most donors like to go and work in areas that they’re comfortable in, and that are high visibility. If you’re working in central hospital, you get to sleep in an air conditioned hotel room that night, and so on. Very few people are willing to go out to the rural areas and live there, and unless we can address the challenges there, we’re not addressing the greater proportion of the problem.

One of your favorite TED talks is Andrew Mwenda’s, in which he criticizes the perverse effects of aid to Africa. Baobab is completely donor-funded. Do you have conflicting feelings about that?

I totally agree with Andrew Mwenda. The question is really about sustainability. The donor-driven model doesn’t have an adequate model for sustainability. That’s my biggest concern. And it’s based on short-term return on investment. If you have very short-term objectives, those objectives are not necessarily the right building blocks for long-term progress. Actual progress is often a very slow process in which you don’t see a lot of visual progress.

It’s very hard to work with a donor on a long-term plan. And unfortunately, as Andrew Mwenda points out, governments are much more likely to sit down with the World Bank than they are to sit down with a neighboring government and talk about a trade agreement. I find this is also true in the work we do.

Our medium-term solution to sustainability is to show that this technology is not only about improving patient outcomes, but about reducing healthcare delivery costs. If we can do this, we change the question from, “Should we install electronic medical record systems?”, to “How do we finance the initial investment?” I believe this is still a critical area that can significantly benefit from short-term donor investment.

Baobab has been in Malawi for 10 years. We will never leave Malawi, because we’re truly a Malawian organization.

Baobab has registered more than 1,300,000 patients, and has more than 100,000 HIV patients managed with the Baobab HIV electronic medical record. With such a successful model, why haven’t you expanded to nearby regions?

Baobab is a Malawian organization of the people, by the people, and for the people. We explicitly do not want to go outside the borders of Malawi. We focus on solving problems that have very Malawi-specific solutions. Neighboring countries are experiencing similar problems, definitely, but their approaches to how they are addressing those problems are not necessarily identical. We will create a custom piece of software that exactly mimics the national strategy for managing patients on any particular drug regimen.

If I were to say, “Here’s a free piece of software, Rwanda, or Zambia, or Mozambique, go ahead and use it.” They’ll say, “You know what? It’s not in French.” Or, “It’s not in Portuguese, and these aren’t the data elements we collect.” My concern is that if we try and solve everyone’s problem, we’ll end up not solving anyone’s problem.

Malawi’s success notwithstanding, there is remarkable work going on in other developing countries. I’ve never worked in Rwanda, but everything I hear about Rwanda is that the government is really committed to eHealth. They’re really putting the donors to task and saying, “If you really want to pay for this, and this is what you want us to do, show us how this fits in and show us why this makes sense.” I’m planning to go to Rwanda this summer and better understand what it is they’ve done that’s allowed them to take this strong positive stance.

There are many aspiring social entrepreneurs out there who are trying to take their passion and ideas to the next level. What is one piece of advice you would give to them based on your own experiences and successes? Learn more about how to become a great social entrepreneur from all of the TED Fellows on the Case Foundation blog.

If Baobab is a success, it’s a success not because of me, but because I brought the right people in at various times. It’s a bunch of Malawian people who did this.There were several committed “azungu” (foreigners) involved over the years — Mike McKay, Zach Landis Lewis, and Jeff Rafter, for example — but I think we were just the catalyst.

If I look back at what went right and what went wrong with my career, I don’t think I listened to my heart as much as I should have. When I deviated from what my vision was, it was because I listened to other people, in spite of my gut telling me, “That’s not the way to go.”

It’s an interesting thing about advice. It doesn’t matter who you listen to. At some point, somebody will give you bad advice. That’s not a bad thing: you shouldn’t do what everybody tells you to do. You get advice, you weigh it, and see how it fits with your vision. I probably allowed myself to be influenced in certain areas more than I should have.

How has the TED Fellowship impacted you?

I went to the conference at a time that was very emotional for me already. I was just finishing my PhD, and I’d just hired somebody to run Baobab in Malawi, and was handing over the reins of the organization and moving into the position of Chairman of the Board of Trustees.

The TED Conference was a mind-blowing experience. It’s hard to describe to people. Imagine when you’ve been out in the evening and have been to a performance, or a concert, or a ballet, or the symphony or something like that, and you leave there and you’re just sort of floating a little bit, and you’re thinking, “Wow, that was really amazing.”

Then imagine walking out of that door, and into another one. And then another one. And then another one. And then the next day, ten more.

You sort of develop this sense of euphoria at the conference, that something magical could really happen. Well, it is happening. But it sort of blurs that boundary between reality and imagination.

Being outside of my normal domain also got me interested in what I might do as another career. I got very interested in renewable energy as a result of attending the conference.

What are you up to now?

I recently accepted a faculty position at the University of Pittsburgh, where I’ve established a new Center for Health Informatics for the Underserved, of which I’m the Director. I’m also teaching a new course I’ve developed called the Principles of Global Health Informatics. I’m still trying to find a balance between my Baobab life and University life that will allow me to leverage the synergy between both.

Comments (3)

Pingback: Healthcare and Technology