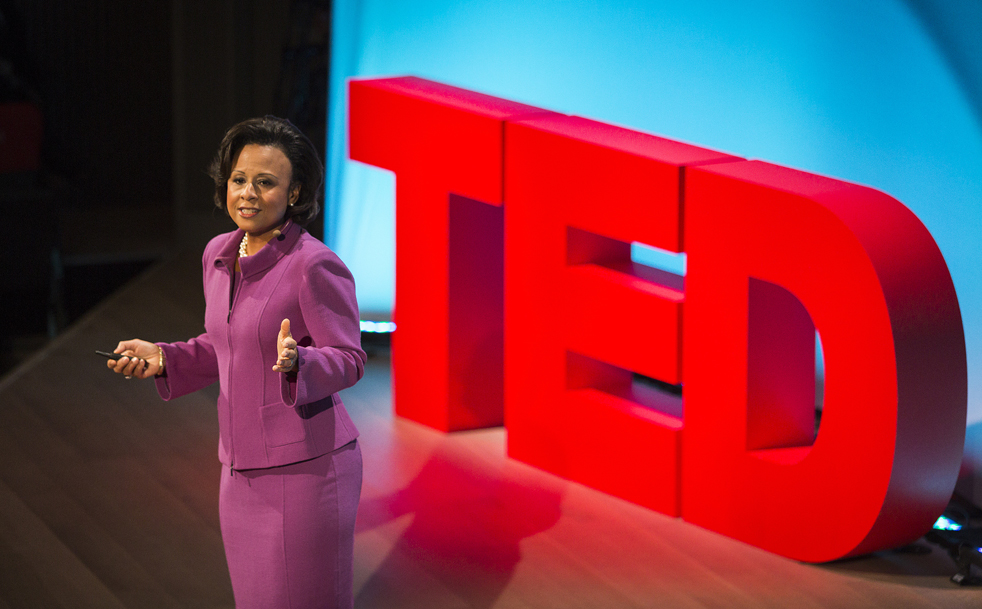

Paula Johnson’s talk at TEDWomen 2013 gave attendees a new appreciation of why it’s so important to include women — and female animals and female cells —in medical research. Photo: TED

“Women’s health is an equal rights issue as important as equal pay.”

When Paula Johnson uttered this sentence on the TEDWomen 2013 stage, the audience broke into spontaneous applause. “At that moment, it said to me they got it,” she says.

Johnson has been working for decades to raise awareness about how diseases behave differently in women and in men — and calling out how much more we know about men’s diseases than women’s. For example, in men, heart disease typically manifests as a blockage, but in women, plaque tends to be distributed more evenly in arteries. The two diseases, though similar, requires different kinds of test to diagnose — but this was not widely known. Many women with heart disease, as a result, simply didn’t get diagnosed or treated at all.

Compounding the problem, until around 20 years ago, women were rarely the subjects of medical research, leading to a stunning lack of information on how diseases — and different medications and treatments — affect them. Even today, while women are part of clinical trials, it’s not necessarily at representative numbers.

So giving her TED Talk, says Dr. Johnson, was like knocking over the first domino in a long chain toward getting her message heard.

“I would say that in a year, we have seen more progress on this issue than we have literally in the past 20,” says Johnson, chief of the Connors Center for Women’s Health and Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “My TED Talk was the breakthrough in allowing me to deliver the message to a broad audience.”

Since her talk went live on TED.com in early 2014, good things have been happening. Newspapers and magazines have increasingly covered the gender gap in health, often quoting Dr. Johnson and other experts from the Connors Center. The center has started work on a policy brief with the Kaiser Family Foundation, and is working with The Jacobs Institute to study how sex-based science can be translated into clinical care. Johnson herself was elected to the Institute of Medicine.

The talk also kicked off a big moment for the movement: the National Policy Summit on the Future of Women’s Health in March 2014. This summit brought together heavy hitters like Senator Elizabeth Warren, FDA commissioner Margaret Hamburg, and journalist Lesley Stahl for a day-long think on how to push forward the idea of sex-specific medical research. And it had real results.

.

Johnson and her team had long hoped to hold a summit like this, but her invitation to speak at TEDWomen gave the project a jump-start.

“TED really set the stage,” she says. “As I started to develop the TED Talk, we began to crystalize how to create a powerful story that could be accepted, understood and embraced by the academy, by advocates, by Capitol Hill policymakers and by the general public. You have to think long and hard to get to, ‘What is the best way to articulate my message?’ The goal for me was to create a base of knowledge that was going to move to the next level of change.”

As Johnson wrote her TED Talk, plans for the summit came together, and things accelerated after her talk was posted. “It was really electric,” says Johnson of the March 2014 event. “It was people from academia, pharma, TV news, policymakers all together, getting educated and really thinking about: what is the path forward? People came to the table with visible passion, and I think it was a kind of clarion call for change in the way science is done.” In a breakout session, Stahl interviewed activist Vicki Kennedy and the FDA’s Hamburg, asking tough questions like, “Do you even know which of all the drugs the FDA has approved which men and women metabolize differently?”

One of the most passionate people in the room: Elizabeth Warren. In an interview later, the Senator shared why the topic is so important to her. “Part of this is personal,” Warren said. “My mother was in the hospital for a little surgery. She was going home the next day. She sat up in bed and said to my daddy, ‘Oh there’s that gas pain again,’ and then fell back dead. The autopsy showed that she had advanced coronary disease, which had never been diagnosed and of course never treated. Back then, no one knew that women had heart attacks too.”

Johnson was thrilled to find such an avid supporter of her work. “[Elizabeth Warren] said to me at the end of the summit, ‘We are going to work on this together,’” remembers Johnson. “And she’s done it. She’s followed through.”

Warren, along with nine other House and Senate Democrats, requested a report from the Government Accounting Office (GAO) on the inclusion of women in clinical trials supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The report is expected in August 2015 — and Johnson is hugely excited about it. “Once you get a GAO report, it can form the basis for policy moving forward,” she says.

It is even possible, however, that the NIH may move forward on the issue before the report. Johnson says, “The NIH made an announcement that they, at some point in the near future, will require the inclusion of female animals and female cells in preclinical research, and will also require the inclusion of adequate numbers of women to get meaningful results in clinical trials. They’ve called for input to how to implement such a change, and we’ve provided significant input on that.”

Lesley Stahl interviews Margaret Hamburg of the FDA during the Women’s Health Summit in 2014. Notice Paula Johnson in the front row. Photo: Brigham and Women’s Hospital

At the summit, the Connors Center released a report of its own, called Sex-Specific Medical Research: Why Women’s Health Can’t Wait. It outlined progress and roadblocks on the way to health equity in cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, depression and Alzheimer’s — plus a detailed, bullet-pointed action plan.

One focus of the report: that peer-reviewed journals should require researchers to disclose the gender breakdown of the subjects in their studies and clinical trials. As Johnson says: “What we called for in the report is almost like a nutrition label, so that authors state up front who’s in their study. And not just for clinical trials, but for any study — whether it be on animals or on cells. Even stem cells are sexed. If you use stem cells to populate a heart — what we call a heart scaffold — if it’s female cells, it looks different than male cells.”

In late 2014, the Endocrine Society introduced a policy for its scholarly journals, requiring that all authors submitting papers disclose the sex of both human and animal research subjects.

The report also lays out what individuals can do to help create systemic change, beginning with pushing their own doctors to consider gender in both diagnosis and treatment of ailments and letting politicians know that greater accountability on the issue of gender-equity in medical research is important. Another approach: Johnson wants to see women who are involved in disease-specific advocacy organizations — organizations dedicated to Alzheimer’s, diabetes, etc — bring up gender. “People need to start asking: do you consider sex in your approach to science or care?” says Johnson. “And if the answer is ‘no,’ then: ‘Why? Where are the opportunities to do that?’”

So far, Johnson has been thrilled with the changes that have come from the summit. “Our report lays out a path forward, and it has been the path forward,” she says. “There has been significant momentum. We’re not there yet — there’s still a lot of work to do — but we have really seen a sea change.”

As all of this has happened, Johnson continues to hear from men and women daily about her talk. “The one thing I constantly get from my TED Talk is, ‘I never knew this. I just assumed [research on women] was done,’” she says.

She’s proud that her talk could surface an issue in healthcare and science that had largely flown under the radar. “When you have something as basic as the inclusion of women — and female animals and female cells — in research and it’s not being done routinely in a meaningful way: this is our health,” she says. “There needed to be a rallying call.”

Comments (3)