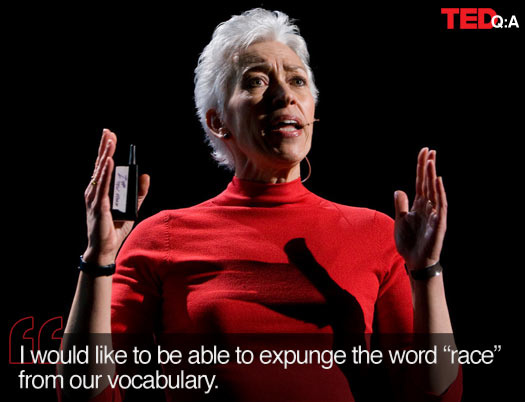

Before her TEDTalk went up on Friday, anthropologist and skin expert Nina Jablonski took some time out of writing her new book to talk to the the TEDBlog. Nina had a lot to say about how our skin affects how we are perceived, sometimes in ways we want it to and sometimes in much more pernicious ways.

Are you excited that your TEDTalk is being posted?

I’m very excited, very happy. I greatly enjoyed being at TED and the atmosphere of the gathering. Also, I think the spread of TEDTalks via the Internet is even more important than being there. It’s all over the world. I know people all over the world who watch TEDTalks. It’s important to get these ideas out to more and more people. One can never predict where one’s idea might go.

So, of all the things you could study, why skin?

It started as an accident more than 15 years ago. I was asked by a colleague to give a lecture in his class, on skin. This lecture was being give to an introductory class of human biology. I read up on the relevant materials, but then realized that I also wanted to tell the students about the evolution of skin. As I started looking for information, I discovered that the research on that topic was scarce. My interest was piqued by this deficiency of information on the evolution of our largest organ.

Then, I went to a seminar where I saw a lecture by a colleague on skin that gave me incredible insight. The insight was sufficiently important that I decided it was time to run with it, despite my lack of experience in this research area. The next step was that I wrote a paper to propose my new hypothesis. That was 17 years ago, in 1992. I just put it out there, and I thought if anything ever arises, at least I’ve written it. In the meantime, I kept my antennae twitching for new research.

Then, in 1995 to ’96, new data on UV radiation at the Earth’s surface was released from NASA. This allowed me to investigate my hypothesis rigorously. With my husband’s help, he’s a geographer and statistician, that’s when the project really started. We began developing data on why UV levels and skin color correlated. Then, in 2003, the University of California press said, “You really should write a book on skin in general.” So, I said, “OK.” One thing led to another. It was the prompting of my editor that got me to think about including the evolution of skin, not just skin and the sun. It’s a very broad topic.

Speaking of which, in your book you talk about skin decoration and how humans are unique in decorating our skin by tattoos, make-up and more. What do you think this means?

We do have an awareness of ourselves that allows us to engage in willful decoration that other animals do not engage in. These dramatically change our appearance and how we are perceived. You can put on a particular set of clothes and make-up or body paint and have a completely different perception.

We can make ourselves appear more sexually appealing to members of a particular group, or more threatening. At football games, people wear all sorts of face paint because they want to look fierce and war-like. These are very specific visual signals that are meant to get particular responses. These things have real evolutionary value. There’s an advantage to being good at putting on make-up and sending the correct signal. You don’t have to look very far. Open up any women’s magazine and you’ll see tips on applying make-up. But all those tips are geared to creating a particular appearance that we know from evolutionary biology makes one appear more sexually attractive.

All the ways of decorating skin make statements that impact how people treat you. Knowing how to decorate can even make one more successful at attracting certain groups of friends.

One of the most obvious factors in our skin’s appearance is its color, and you talk about the origins of color in your talk. But, what about how skin color has historically affected our behavior towards each other?

Skin color is the story of pigment in the skin, having been determined by UV radiation. If your ancestors were closer to the equator, you are dark and if further away, you are lighter. The biology is very straightforward. But, history is much more complicated and hard to comprehend.

People have placed values in skin color based on who interacted with who. The most insidious of these interactions is the Trans-Atlantic slave trade in the 1500s. A lightly-pigmented people in a position of power and mobility went by ship to a different part of the world where they found a darkly-pigmented people. As we know, they created slaves of these people on the African continent, in the equatorial area. Many of the problems with color we face today came to be because of interactions started by the slave trade.

The easiest way to establish the dominance needed for the system of slavery to function is to establish visual mechanisms, which in this case was the color of these slaves. What you then see is the literary development of black as bad, negative, as mentally and spiritually inefficient. This is the toxin that created created much of the race debate.

People are color-coded in very visible ways. We are very visually-oriented as primates and color makes a big difference to us. We notice subtle differences in color and these can be perceived as social value if given the right narrative. These values exist in India, Japan, China and elsewhere. In most places where you find a gradation of color, you get this phenomenon of colorism. There’s a general prejudice against darkly pigmented skin and a bias toward lightly pigmented skin.

Even within African-American, Caribbean and Latin American communities you can find this prejudice and it’s a derivative of the slave trade. Light brown versus dark brown. And it can be very subtle, this color difference, but it’s just enough for us to distinguish. And this really concerns me, because — what happens to that dark-colored child? They feel that they have limited prospects or possibilities. This to me is the most poisonous aspect. This is one of the most injurious things we can do to a child. Stopping this is part of my life’s work now. I’ll tell you more about that a little later on.

READ MORE: Nina discusses how our skin color will change in the future, her new book and how she takes care of her skin.Do you think that after living in different climates for some time, that our skin colors will ever re-adapt?

Firstly, we already see in major urban centers a tremendous amount of intermarriage between people of diverse backgrounds. Especially in large urban centers, there are many people of different colors now sharing a common culture. These factors can lead to a homogenization of skin tones.

This will not happen everywhere as in more rural and isolated areas we continue to see cultural and color distinction. For example, in North Scandinavia we find very isolated lightly pigmented communities and in equatorial Africa we still find very isolated darkly pigmented communities. So there will continue to be isolated areas with people at the extremes, but in major urban environments there will be much more mixing and eventually matching of color.

But we won’t have any evolutionary adaptions to climate because now we have clothes, shelter, chemical sunscreen and other cultural ribbons used to protect ourselves against excess sun, very much unlike the early days of our species. Biological evolutions on our skin has stopped because we are so good at protecting ourselves against the sun.

However, I must mention that although we are clever, we are not as clever as we think we are. We don’t protect ourselves enough. Lightly-pigmented people are tanning, laying on beaches in Mexico for hours. Darkly-pigmented people have jobs where they spend most of the day out of the sun and have vitamin D deficiencies. There are also very few days during the year in temperate climates that can provide vitamin D to darkly-pigmented people in the right amounts.

You mentioned that you were writing a new book, also to do with skin. Can you tell us a little bit more about your new project?

The new book is about skin color. It’s actually going to address many of the things that we’ve talked about — how skin color evolved, health concerns and issues of perspective and race. The book title is Living Color. I’m trying desperately to finish it this summer and I’m hoping that get it to the publisher and then publicly released by fall, 2010.

I would like to be able to expunge the word race from our vocabulary, but I don’t have the power to do that. It has no biological basis, lots of scientists have shown that. As a social concept it continues to be invented and reinvented. People seem to want to keep it going. I am just trying to shed light on the fallacy of the biological concept and the idiocy of social concept. We can change the world if we can change these definitions and expunge these concepts from our interactions.

One last, quick, question. The video editor responsible for fine-tuning your talk mentioned to me that she couldn’t help noticing how great your skin was all the while you were talking about skin. Here at TED headquarters, we want to know — what’s your secret?

(Laughter) Well, thank you, but I really don’t have any secrets. I use all over-the-counter skin products, no prescriptions. I live a healthy life, exercise, eat well, stay hydrated. I guess I also have good genes. Oh, and I avoid overexposure to the sun.

Comments (2)

Pingback: American Steroids Online

Pingback: thermal systems « system zoo