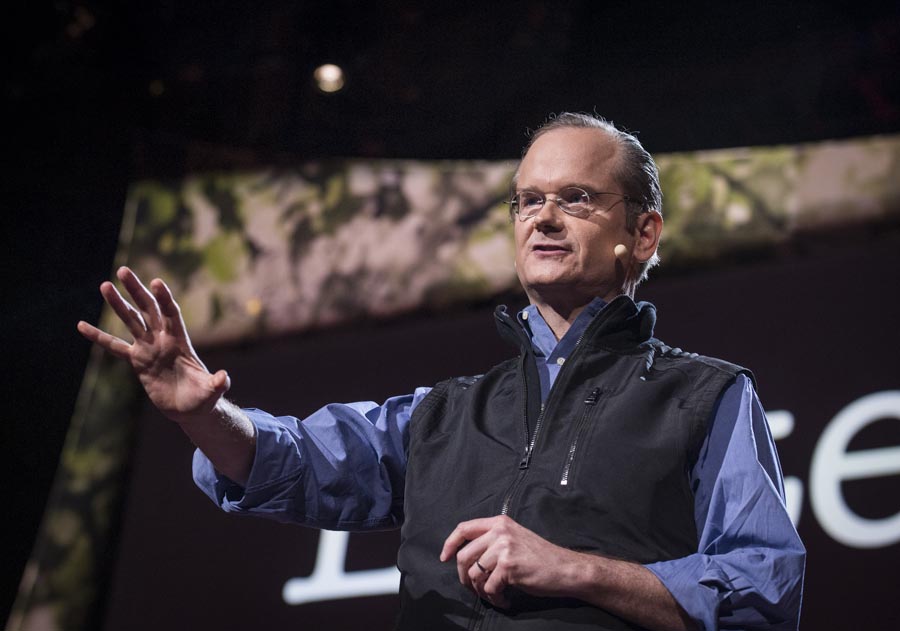

Larry Lessig has been referenced twice this morning, first by Wikihouse’s Alastair Parvin and secondly by the musician Amanda Palmer. So it seems only right and proper that the Harvard Law professor should round off this session of TED2013. He’s here to talk about Lesterland, a fictional land with a population of 311 million people of whom the 144,000, or 0.05%, named Lester are the people really in charge. It’s the United States, of course, and Lessig is using the analogy to help us confront and understand the truth of democracy in the United States. It’s a theme of Rootstrikers, the project he founded to battle the corruption of campaign funding in the American political system, and it’s a topic that has Lessig visibly fired up.

Lawrence Lessig: Laws that choke creativity

Lawrence Lessig: Laws that choke creativity

You see, the United States also has its Lesters, its 0.05%; they’re the people who fund elections. Lessig, who could probably trademark his manner of delivery if that didn’t, you know, go against precisely everything he stands for, has data to prove it. His favorite stat, he says, that in 2012, 0.000042%–that’s 132 Americans–gave 60% of the SuperPAC money spent in the election cycle. It’s these few, he says, who are our Lesters, and our dependence on them is perverting the democracy of the country. After all, if candidates have to spend between 30% and 70% of their time trying to raise funds to get back to Congress, which they do, might that not affect their principles, their beliefs, their ideals, and what they’re prepared to fight for on behalf of the people?

And here’s the rub: whereas in Lesterland, Lesters might comprise a somewhat random selection of demographics, with poor Lesters getting their moment to air an opinion along with the rich ones, that’s not the case in the US. Here, the vast majority of the Lesters are less interested in acting on behalf of the common good than they are in furthering their own interests. The system is twisted, and the competing dependencies on our political system are no less than a corruption, says Lessig.

“The good news is it’s bipartisan, equal-opportunity corruption,” he adds wryly. It blocks the left on issues they hold dear, but it blocks the right too. Yet it seems like no one is prepared to change anything about this borked status quo. Lessig tells a story of then-Vice President Al Gore wanting to deregulate the telecoms industry. “The response was ‘hell no: If we deregulate these guys, how will we raise money from them?'” The delivery makes the line funny, but it’s an awful thought.

“The good news is it’s bipartisan, equal-opportunity corruption,” he adds wryly. It blocks the left on issues they hold dear, but it blocks the right too. Yet it seems like no one is prepared to change anything about this borked status quo. Lessig tells a story of then-Vice President Al Gore wanting to deregulate the telecoms industry. “The response was ‘hell no: If we deregulate these guys, how will we raise money from them?'” The delivery makes the line funny, but it’s an awful thought.

Lessig isn’t here to let us off the hook. We know all this already, he accuses. Yet we ignore it. And we cannot ignore it any more. “We need a government that works.” He refers to the call by former Michigan governor Jennifer Granholm, made from this stage yesterday to get support for a prize fund for clean energy. “It was a punch in the gut to have a former governor stand up and try to Kickstart a national energy policy from TEDsters,” Lessig says. “Is this a third-world nation? Are you serious? We need a government that works! Not one that works for the left or the right but for citizens of the left and the right.” Until we reform this issue, he adds, no other issue has a chance of being resolved.

So how do we do actually solve the problem? Turns out, the solution is easy, and wouldn’t even require a Constitutional amendent. It would need a single statute calling for lower dollar fundraising. The problem? The politics: when so many Congresspeople and senators head to K Street after their time in office–becoming lobbyists, enjoying no less than an average increase of 1,452% in their salary–what possible incentive would they have to change things?

“I get this sense of impossible, but I don’t buy it,” Lessig continues. “This is a solvable issue. Think about the issues our parents tried to solve in the twentieth century–racism, sexism, or the issue we’ve been fighting this century, homophobia. Those are hard issues. You don’t just wake up one day no longer a racist,” he describes lyrically. “This is a problem of incentives. Change the incentives and the behavior changes.” When Connecticut first adopted the system, 78% of elected representatives gave up on large contributions within the first year.

Lessig closes with another challenge, spurred on by a woman telling him he’d convinced her it was hopeless, not entirely his intent. “I imagined a doctor saying ‘your son has terminal brain cancer. There’s nothing you can do.’ Would I do nothing? Would I just sit there? Of course not. I would do everything I could do because this is what love means. The odds are irrelevant. You do whatever the hell you can, the odds be damned.” It is this passion that citizens need to apply to this problem. After all, he adds drily, “even we liberals love this country.”

“When the pundits and politicians say change is impossible, what this love of country says is: That’s irrelevant. We lose something dear, something everyone in this room loves and cherishes, if we lose this republic. We act with everything we can to prove these pundits wrong. And here’s my question: do you have that love? Do you have that love? Because if you do, then what the hell are you, what the hell are we doing?”

When Benjamin Franklin left the Constitutional Convention in 1787, a woman asked him what he had brought with him. The reply: “A republic, madam, if you can keep it.” We have lost that republic, Lessig concludes. “All of us have to act to get it back.”

Comments (8)

Pingback: Larry Lessig: We must take back the Republic | clever nicknames

Pingback: Instapundit » Blog Archive » TAKING BACK THE REPUBLIC: A preview of Larry Lessig at TED2013. Lessig’s speech will be incorpora…

Pingback: My 13 favourite talks from TED 2013 | Sue Gardner's Blog

Pingback: Wizmo Blog » Blog Archive » Taking back the Republic: Larry Lessig at TED2013