How the movie “Pacific Rim” reminded the writer of the deep-seated need to win arguments.

My last fight came after, of all things, the movie Pacific Rim. As my moviegoing companion and I walked out of the theater, he said of Guillermo del Toro’s latest, “That was awesome.” I, on the other hand, thought it was just okay, managing to slightly elevate its robots-versus-aliens premise.

At first, we slightly disagreed. But within 15 minutes, my companion was declaring the movie a sparkling beacon in the tide of summer-movie sludge, a brilliant takedown of the destruction movie genre. I, on the other hand, was calling it everything that’s wrong with cinema today — too much action, too much testosterone and far too high a body count. Wait, but you had fun watching the movie, I thought, even as I railed against it.

As our discussion crossed the 60-minute mark, and my cheeks were fully flushed, I realized that I was no longer simply stating my opinion. I was positioning myself to win an argument, dismissing my companion’s points no matter whether I agreed or not. I was in this fight to be crowned the person most in the right. And it didn’t feel good.

This silly argument left me thinking: What is it about human beings that leaves us needing to be right, needing to get the last word in no matter what? Luckily, two fascinating TED Talks — one posted today and one classic from 2011– speak to the strong desire … and give insights on how we can break through it.

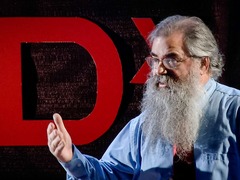

Philosopher Dan Cohen has spent decades perfecting the art of arguing. And yet in today’s talk, given at TEDxColbyCollege, he reveals that he now loses intellectual debates more than ever.

Daniel H. Cohen: For argument's sake

Why? Because he has stopped subscribing to the dominant metaphor that surrounds debates — that they are a war with vicious battles fought and with a clear winner and a clear loser at the end.

Daniel H. Cohen: For argument's sake

Why? Because he has stopped subscribing to the dominant metaphor that surrounds debates — that they are a war with vicious battles fought and with a clear winner and a clear loser at the end.

“When we talk about arguments, we talk in very militaristic language. We want strong arguments. Arguments that have a lot of punch. Arguments that are right on target … The killer argument,” says Cohen, dissecting how we argue. “[But] if argument is war, then there’s an implicit equation of learning with losing.”

In this talk, Cohen unpacks why the argument-as-war metaphor is so limiting — because it creates an adversarial relationship. It puts the focus on tactics (knock down your opponent’s argument) rather than real thought (do they have a point?), and shuts off the possibility of negotiation, compromise or collaboration. Because after all, who is the real winner in an argument? According to Cohen, it’s whoever has their worldview expanded. There’s no reason that needs to be limited to one person. In the ideal situation, everyone in a debate could come out with a greater understanding.

Kathryn Schulz: On being wrong

Cohen’s talk reminds me of Kathryn Shulz’s classic, On Being Wrong. At TED2011, Schulz pointed out a related paradox — that while we all know that human beings are fallible, we are loath to admit when we ourselves are wrong. “So effectively, we all kind of wind up traveling through life trapped in this little bubble of feeling very right about everything,” says Schulz.

Kathryn Schulz: On being wrong

Cohen’s talk reminds me of Kathryn Shulz’s classic, On Being Wrong. At TED2011, Schulz pointed out a related paradox — that while we all know that human beings are fallible, we are loath to admit when we ourselves are wrong. “So effectively, we all kind of wind up traveling through life trapped in this little bubble of feeling very right about everything,” says Schulz.

In a brilliant moment in the talk, she asks: what does it feel like to be wrong? While first instinct might tell us that it feels terrible, she points that’s actually only what happens when we realize that we are wrong. Until that moment, being wrong feels exactly like being right. So often, clues pop up that could reveal to us our error — and yet, we often put up blinders to them. This is fine when it comes to a misunderstood song lyric. But it can be disastrous when it comes to bigger convictions that affect the health and well-being of others — or our planet.

But beyond that, explains Schulz, the need to be right simply keeps us from growing.

“What’s most baffling and most tragic about this is that it misses the whole point of being human,” she says. “If you really want to rediscover wonder, you need to step outside of that tiny, terrified space of rightness and look around at each other and the vastness and complexity of the universe and be able to say, ‘Wow, I don’t know. Maybe I’m wrong.’”

And with that, I am willing to admit: I could maybe, possibly be wrong about Pacific Rim.

Comments (9)

Pingback: What Is January 26 National Day

Pingback: 3 Things Your Couples Therapist Won't Tell You - The Fashionable Housewife

Pingback: Почему ошибаться и проигрывать спор иногда бывает полезно | TED RUS