Healing requires more than technical proficiency; it requires an ability to connect to another person. Healing requires compassion, “a shared sense of humanity,” and the ability to see another’s pain as “the kind of thing that could happen to anyone, including oneself insofar as one is a human being.”

In other words, we have our drugs and our prevention campaigns, but that is not enough. … [We] also need to focus on restoring the human connection that the disease tears asunder. As a nurse and HIV counselor I spoke with told me, “When you have HIV, you’re the type of person that is supposed to be loved by people. There is need they have that love, because when there is not love, the tension will be too much and they can easily die—not from the sickness but the heartsickness.” — from Our Kind of People

Physician and novelist is an intriguing combination. Why do you feel called to write fiction, and how do medicine and writing fit together in your life?

I’ve been writing since I was really young. I suppose I’m pulled towards fiction because I really like the freedom it gives me. My fiction tends to be more realistic at the moment, but the medium allows for a use of language and imagery and imagination that helps me — and hopefully the people who read my writing — to see the world a little differently, perhaps to untangle complex emotional, social issues at a slower, less charged pace than we are allowed to in this world where almost everything is news and the news never stops. I love playing with language and the rhythm of language — for some reason, this seems so much easier for me to do when I get to make things up than when writing nonfiction.

In terms of medicine, I’ve generally been pretty interested in public health issues as they relate to sub-saharan Africa on a broad scale — HIV/AIDS, malaria etc. I’ve done some consulting work on malaria and also had a chance a number of years ago to work on a broader scale on issues of health access and health systems in sub-Saharan Africa, as a junior employee at the Millennium Villages Project. I think ultimately, once I finish my residency, I’ll likely have a broader-scale public health related orientation, but I’m also very interested in pediatrics and adolescent medicine. These are and will be quite a big part of the health landscape in sub-Saharan Africa — indeed globally — for many years to come.

I don’t know fully yet how medicine and writing fit together for me. I know that being a physician allows me incredible access and insight into the human condition — which is what every writer seeks to elaborate in his or her work. But the two as professions are rather incompatible, to be honest. They are both very jealous lovers. I think this is going to be one of those things that I just have to learn to work out, that I’m sure will provide numerous twists and surprises as my career develops. I’m excited about it, but also of course a little apprehensive.

Tell about your experience growing up in DC, raised by Nigerian parents.

DC was a great place to grow up, but having parents from another place and having one’s own sense of self and identity rooted in another cultural climate was definitely emotionally demanding. There are obvious contrasts between first and developing world living experiences, and between a more individualistic American cultural experience and the more community-oriented Nigerian (more specifically Igbo) one.

What stands out most for me about growing up between the two was having to act as a bridge from a very early age. People tend to access other environments through people, and whether legitimately or not, one’s status as “other” automatically makes one the go-between or spokesperson. Even in this relatively international environment, I felt I was always explaining or representing another world for my classmates, church congregation and so on.

What startled you the most while researching this book?

Nigerians are relatively conservative, and yet everybody I spoke with was very open about sex and sexuality (which of course is integral to the nature of the epidemic). People also had more to say than they are normally allowed to in the global community about HOW they are represented and viewed and what this means to them. I was really excited to hear people find the humor in the presence of the epidemic, to hear complex understandings of both the disease and how it changes the representation of Africa and African bodies domestically and globally, and to hear quite a bit of hope and optimism in the continent’s ability to deal with the epidemic effectively.

The desire to write Our Kind of People actually came from working on health systems in sub-Saharan Africa and realizing that the language that people use to speak about certain dire issues in the health space seemed to be dehumanizing even as it sought to help. It made me realize that there’s a lot lacking in the discourse about many of the problems in the region, and about the interventions and the roots of these interventions. I thought it would be interesting and necessary to take a look at both how people speak about disease in the larger international context but also how it’s spoken about on the domestic front — and how the two forms of conceptualizing HIV/AIDS impact each other. I think having a medical background made understanding a lot of the technical experience easier, but really and truly what I was searching for from the people I interviewed and interacted with was a better understanding of how to view myself as an African and Nigerian in the midst of this disease, and how to responsibly represent that identity to the rest of the world.

This is your first book-length work of nonfiction. How did your experience as a novelist help shape Our Kind of People?

I think being a novelist (rather than a journalist) and trying to write about this epidemic brings a slightly different viewpoint and a slightly different appreciation for how language and the act of storytelling are as important as the “facts” about the situation. I was perhaps more interested in HOW people told the stories about their experiences than just the substance of that experience. I think that’s probably a novelist’s bent — because we’re so concerned with how to represent.

In what ways has this book affected your own outlook on life?

First it’s being done has made me a lot less stressed! But I think professionally, it has made me much more interested in the power of nonfiction and the process of writing that kind of work. I write highly subjective nonfiction and I like the thought of work that, while being about a “real” issue, questions more and more how we construct this reality, which impacts how we deal with the reality. It’s also good to have had the chance to spend so much time with one subject.

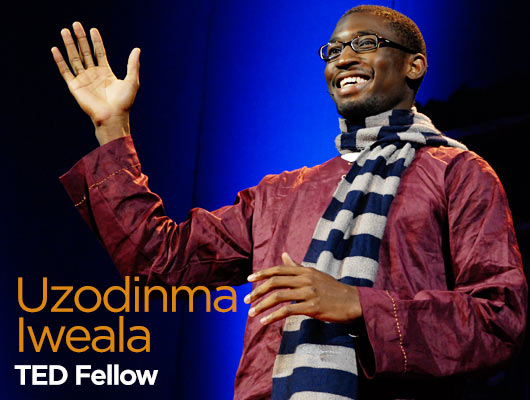

You were one of the original class of 100 TEDGlobal 2007 Fellows, in Arusha, Tanzania. How has being a TED Fellow affected your life and work?

Oh man — being a TED Fellow has been awesome. The community of folks I was able to get to know my fellowship year — everyone is doing wonderfully exciting things, and I’ve been able to reach out to them for help on projects, to let them know about things that might help in their work. Also just being exposed further to people who can make what often is very technical and specific work sound digestible and exciting helps when trying to do the same with one’s own work. It was an amazing experience to have had!

What’s next?

Our Kind of People comes out in July. Then a couple more projects — I’ve got to finish a novel, and then I’m working on another nonfiction book about post-conflict states in sub-Saharan Africa, so we’ll see.

Our Kind of People will be released on 10 July and is available for preorder from Amazon.com.

Comments (2)

Pingback: Hope speaks: Fellows Friday with Uzodinma Iweala « Content Curated By Darin R. McClure & a few photos