Becci Manson is a high-end photographic retoucher who works with client like fashion magazines to tart up glamorous images. She and her friends, she says, are pale gray creatures hiding from sunlight in dark, windowless rooms. “We make skinny models skinnier, perfect skin more perfect, and we make the impossible possible.” The field comes under criticism for that, but, she says, this is expert, deeply skilled and artistic work.

But Manson isn’t here to wow us with her wizardry. Instead, she tells a more personal tale. She was at home in New York in March 2011, as the tragic events of the earthquake and tsunami unfolded in Japan. She found that she couldn’t sit by, so she volunteered with the organization All Hands Volunteers to head to Japan for three weeks to do what she could to help. In May, she made her way to the small town of Ofunato, in the Iwate prefecture, where the water had reached 24 meters in height and two miles inland. Her work included clearing canals, ditches and rice paddies of debris, gutting homes, and clearing tons and tons of stinking rotting fish carcasses from the local packing plant. “We got dirty,” she says. “We loved it.”

Yet a funny thing happened in Japan. Almost everywhere, people were finding photographs and albums, handing them in to refugee centers for safekeeping. “It wasn’t until this point that I realized these photos were a huge part of the loss these people experienced,” she says. “As they’d run from the waves, everything from their lives had to be left behind.”

As she was working to clean the town’s onsen, or communal bath, she was asked if she could help to clean some of the photographs that were being stored there. “It was inspiring and emotional,” she said. And it helped her to have an epiphany. “As I cleaned the photos, some over 100 years old, some still in envelopes from the processing lab, I couldn’t help but think as a retoucher that I could mend that tear or mend that scratch. And I knew hundreds of people who could do the same.” That very evening she reached out to some friends on Facebook. “By morning the response was so overwhelming I knew we had to give it a try. So we started retouching photos.”

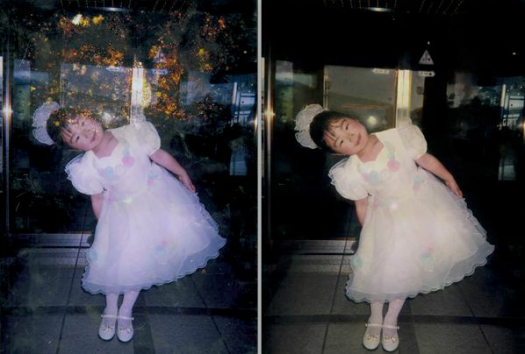

This was the first picture they worked on. “It was not terribly damaged, but where the water had caused discoloration on the face, it had to be fixed with such accuracy and delicacy. Otherwise that little girl isn’t going to look like that little girl — and that would be as tragic as having the photo damaged.” Right on. The audience claps.

More photos came in. More retouchers were needed. Within five days, 80 people from 12 countries had volunteered. Soon, 150 people were working on the project. They expanded to other towns in Japan, too, setting up scanning equipment in temporary photo libraries where sometimes people had neither seen a scanner or even a gaijin. “Yet within ten minutes of finding a lost photo they could give it to us, it was scanned, uploaded to cloud server, downloaded by a gaijin stranger on the other side of the globe and starting to be fixed,” she says. Such is the power of technology and the universal desire to help. The time to get the pictures back, of course, depended on the level of damage: it could take an hour, but it could take months.

She shows the before and after shot of this image: “The kimono had to be pieced together and hand-drawn.” It’s painstaking, emotional work. It’s easy to do more damage than help. “As my team leader Wynne once said,” Manson comments, “It’s like doing a tattoo on someone. You don’t get a chance to mess it up.”

It’s also personal work. Becci shows one small family portrait of a man, woman and two sons, a photo like millions of others in the world. When the woman in the picture came to get the retouched image, she shared her story. Her husband, a firefighter, had the job that day of trying to close the tsunami gates. On the day of the flood, he headed toward the waterfront. Her two young sons were at different schools, and one of them was caught up in the water. “It took her a week to find them all, and to find they had survived.” The woman gave her youngest son the restored family photograph for his 14th birthday. “This photo was the perfect gift for him,” recalls Manson. “It was something he could remember from before, that wasn’t scarred from that day in March when everything in his life had changed or been destroyed.”

After six months, 1,100 volunteers had worked with All Hands, hundreds of whom had helped to hand-clean 135,000 photos. 500 volunteers from outside of Japan helped with the work, too, while they kept costs to a minimal $1,000 for the entire project. It’s wonderful work, and the audience loves it.

“We take pictures constantly,” she closes. “The photo is a reminder of someone or something, a place, a relationship, a loved one. They’re our memory keepers, our histories, the last thing we’d grab and the first thing we’d look for. That’s all this project was about, about restoring those little bits of humanity and giving someone that connection back.”

The project changed lives, not only of those who had their memories restored, but also of the retouchers, who got to work beyond their windowless rooms. She concludes with an email she received from a retoucher, who was struck by a family photograph that had been restored. “It struck a chord,” she wrote, “because a similar photo from my family, my grandmother, my mother and me and my newborn daughter, hangs on our wall. Across the globe, throughout the ages, our basic needs are just the same, aren’t they?” The audience agrees.

[All retouched images c/o All Hands Volunteers ]

Photos: James Duncan Davidson

Comments (3)

Pingback: Photo Retouching for Humanity : Unique Photo Blog, News and Reviews

Pingback: Loving People, Changing the World, one photo at a time?

Pingback: All Hands Volunteer Speaks at TED | All Hands Volunteers