Artist Sharmistha Ray has spent her life moving between India, the Middle East and the United States, discovering, layer by layer, her own sense of self, sexual identity and artistic vision in contrast or harmony with each new environment. Now, as her latest exhibition Reflections + Transformations is set to open at the Aicon Gallery in New York City on October 24, she tells the TED Blog about how her journey has unfolded so far, taking her from figurative art to abstraction and back to vibrant colors and lush, sensual textures that celebrate and reclaim the female body.

You have quite a complicated background. When people ask where you are from, what do you say?

It’s complicated because I’m an artist. People want to know where you’re from as a way of understanding your deepest creative impulses. I started to define myself as diasporic because the many migrations in my life played a very big role in terms of defining who I was, as well as my outlook on life and my artistic practice. I was born a British citizen in Calcutta, but spent my growing-up years in the Middle East and then migrated to the United States with my family later on. I didn’t stop there; a residual nostalgia beckoned me towards India, and after exploring Kolkata for a few months in 2006, I moved to Mumbai and made it my home.

Growing up gay in a traditional Indian family in an Islamic society in Kuwait also created its own displacement. I experienced oppression very early on within my family and society. My sexuality, which started to emerge in my early teens, was a terrifying realization for me. I lived in mortal fear of anyone knowing my dark secret. But ironically, the fear also bore my love for art. It was through art that I was finally able to find my own voice.

Even though I spend most of my time in Mumbai now, I can’t attribute any one of my multiple social, linguistic, cultural, queer, ethnic and geographic ties as the singular source of imagination. It’s really the grazing together of all these identities that has created a messy hybrid form, with many points of location. I am even starting to recast the term “diaspora,” as it feels limited to a binary of homeland and not-homeland. Once the migrant has moved back to the homeland, does he or she continue to be “of the diaspora?” I’m gravitating towards a new term I encountered in reading Gyan Prakash’s excellent historical account of Mumbai in his book Mumbai Fables. He revisits the notion of cosmopolitanism throughout the book, and it struck me that to be “cosmopolitan” strips the subject of a desired location or need to belong. To be “cosmopolitan” essentially means “being in the world.”

What prompted your decision to move to India?

I was curious — and curiosity is probably the starting point for deep infatuations. I had schooled in Kolkata for close to two years during the Gulf War in Kuwait, where my family lived at the time. Becoming a refugee and living in forced exile with my family formed, at a young age, a confusing network of associations between stability and belonging. As I matured as a thinker, the idea of India took shape as a sort of dreamland, a place of possibilities. I wanted to live without the burdens of identity politics for a while and investigate a more poetic entry point into the question of “being.” Of course, I’m not saying that identity politics is exclusive of poetics, but my work had become riddled with an anxious rhetoric caught between the binaries of “self” and the “other.” I wanted to find a different way of locating myself in a milieu that accepted me first as “Indian.” Interestingly, in India I found myself thrust into other negotiations — with gender and sexuality in particular — which took me many years to untangle. And despite my initial longing to connect to an Indian identity, I am as much an outlier there as I was in America, as I am anywhere else!

You mention gender and sexuality. When did you start exploring these themes in your work?

I started in the last year of high school. Although I lived in a conservative Islamic society in the Middle East, I became emboldened in my final year of art studies and decided to take the plunge. But as I had to be careful, the work is very subtle. In those early works, some of which are lost now, the narratives center around myself and a female agent, but there’s always this physical and psychological distance between the two figures in the frame. It mirrored my life at the time, and the feeling of disconnect from my family and society.

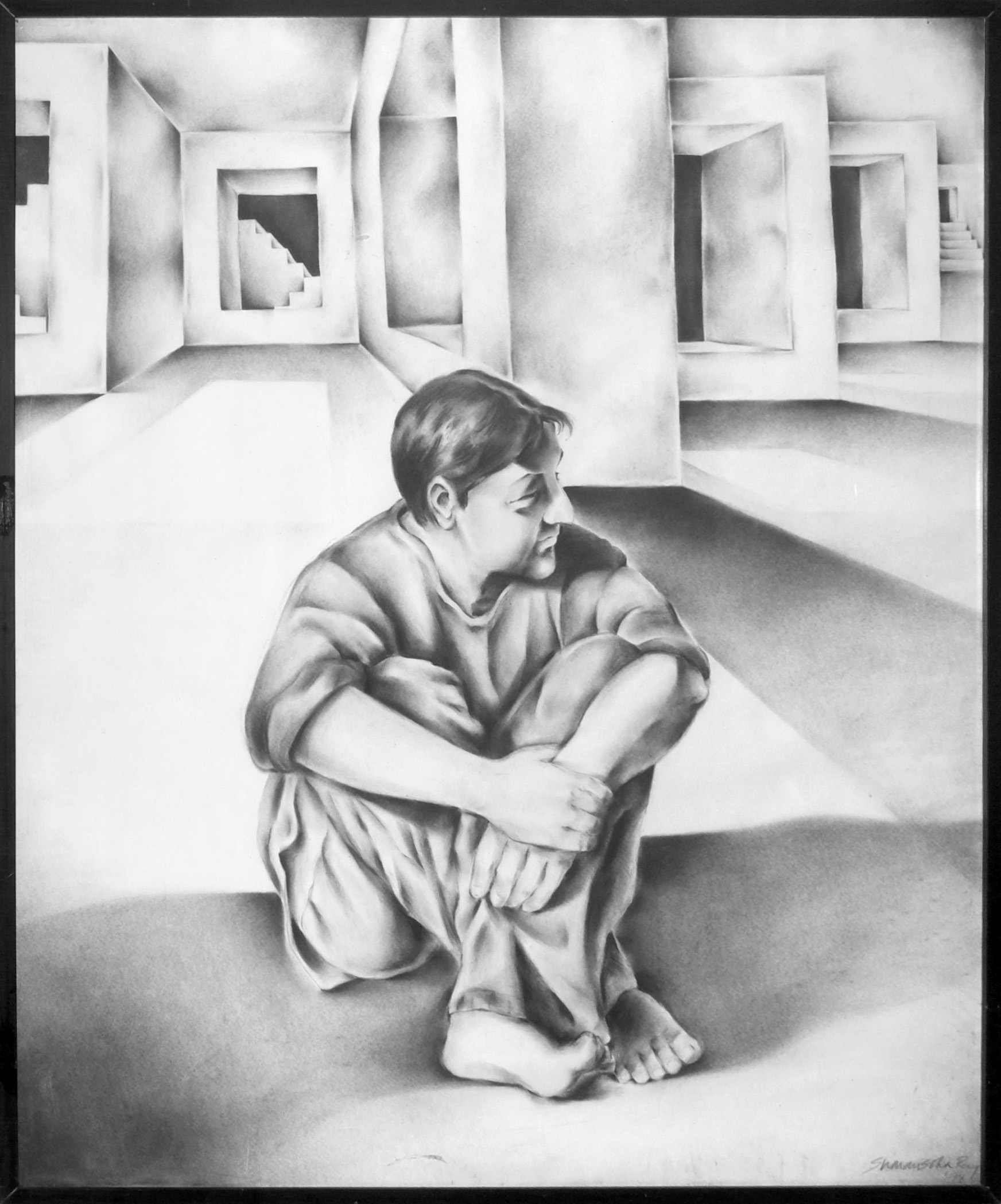

I continued my explorations into college, and received a grant from an alumni organization called BiGLATA in my first year. It was only $2,500, but a lot of money for me, as I was a student. I locked myself away in the summer of 1998 in the basement of my family home in New Jersey and produced a body of large-scale charcoal drawings, which I exhibited together as Queer Series in the fall semester of my sophomore year. That was probably my first solo show.

These works are all about dislocation, which came out of a period of intense questioning about selfhood in relation to society, culture, family, gender and sexuality. My family had just immigrated to America from Kuwait at the same time I went to college, and college gave me the space and environment to let bottled up and repressed impulses out. At the same time, the new culture in America added another layer of complication. I didn’t really get American culture at the time, I didn’t understand the references or relationships and felt even more acutely the isolation many students feel being out in the world for the first time. My art became a way of making sense of the world around me, and identifying my inner struggles.

It must have been tricky to negotiate your different identities in India.

India had been embedded in my consciousness from the time that I had lived there during the Gulf War period in the early ’90s. It had provided a refuge for my family at a very trying time, and it seemed like the logical next step in my investigations into selfhood. I had also become quite interested in Indian contemporary art while interning at a gallery in New York that was showing major artists from India during my graduate school years. These artists’ works revealed a dynamism that made me curious about the society, culture and politics they were reflecting on. I moved to India in early 2006, and spent the first 10 months living in Kolkata. I set up a studio in South Kolkata at my paternal grandmother’s house, and just tried to work every day. It proved rather challenging, as the rose-tinted shades soon came off and I realized I was in a very claustrophobic environment. But it gave me the time and space to explore my impulses in an honest way. I didn’t have anyone looking over my shoulder, so I went back to these small colorful abstracts I started and abandoned at graduate school.

Since I was living amongst extended relations for the first time, I realized quickly that being a woman made me more vulnerable in many respects. Despite that, my time in Kolkata was productive, but on a deeper level, it allowed me to get in touch with myself. I spent many hours reading, learning, understanding. I made many small studies and experiments. Looking back, it was a very rich and textured time. I looked at everything Kolkata had to offer: the architecture, the culture, the textile traditions, the crafts. The city was exploding with visual cues, and these cues resonated with me. The most important development in my practice at this time was the introduction of color. Surrounded with so much color, my relationship to it became less plastic, and more organic.

After a few months, I knew I had to find an alternative to Kolkata. It had become easy to live there, because the cost of living was cheap, which allowed me to just focus on my work, but the feeling of oppression just became too much. An opportunity came from Mumbai. I was invited to give a lecture at a major museum there by a prominent group of art patrons, and I took my first trips to the city in August and September. I was very fortunate in that I landed a dream job at a major contemporary art gallery in the city. By October I’d moved there and have been there ever since. Mumbai is a pretty incredible metropolis; it’s like a densely layered sponge cake. It’s endlessly absorbent and changing all the time. There’s an intensity in the people, in experiences and the way of life. It’s rife with contradictions and contrast. I just love the city.

How were your first years in Mumbai?

Working in a leading contemporary gallery was incredibly exciting. Life was very fast, I traveled like crazy, which suited my wanderlust. Initially, I lived from paycheck to paycheck as Mumbai is a very expensive city, but I was in my twenties, and I was ready to take this big gamble with life — and it paid off! The recession was a very difficult time. I saw the business I had worked so incredibly hard to help create crumble overnight. In the following years, I also started to paint seriously again. I was determined to get back to the reason that had brought me to India in the first place and continue that story for myself. It wasn’t a popular decision, as many wondered why I would leave a successful and promising management career to start from scratch.

How has your work been received in India?

The response to my debut solo exhibition, Hidden Geographies, was pretty remarkable. By and large, people loved the work and the exhibition did really well. It was also written about quite extensively, so the public was very positive and responsive. The paintings are large abstractions, and they are very beautiful. I am interested in canonical ideas of beauty and aesthetics, and while the whispers of sexuality lay embedded just under the surface of these works, it’s really the aesthetics that one engages with first. However, I will say that the metaphorical and poetical nature of my work is in large part due to the censorship that presides over the cultures I’ve had some of my most formative experiences in — the Middle East and India. It’s not safe to be all that explicit, less so in India, but again, it depends where you are. Mumbai is more open than other cities, but still has the strong puritanical presence of right-wing Hindu politics at play.

Forbidden Pleasures, 2011

So how did you begin to paint the female nudes? They seem like quite a leap, considering that need to be cautious due to censorship.

Censorship and my awareness of it — my frustration with the invisible cloak upon my sexuality in the Middle East, in my family and now in India — has, in a way, led me directly to this new body of work, Reflections + Transformations, anchored by the female nude. Here, the self-conscious charge of sexuality is very much present. My approach to the female nude is a very intimate one, born of a personal gaze. It was important for me and for my work to make this statement at this point.

I decided I needed to be more bold and see if this work resonated once I put it out there. It’s probably the most autobiographical work I’ve made since the Queer Series, when I used my own self as the protagonist. I’ve always sensed the glorious artistic potential locked away in the human body, but in my early years, I was deprived of it in art and life. There were no art museums or libraries in Kuwait that carried such pictures. I remember a picture encyclopedia I received one birthday, in which a big, black marker had been used to censor the sexual organs of Michelangelo’s David and any other images that involved nudity or sex. The human body and its sexual desires came to symbolize a subversion of normality and a place of intrigue, and that was more intensified by my being queer.

There’s so much fear about women expressing their freedoms in both Middle Eastern and Indian societies, and fear is contagious. I don’t want to live with fear. The rash of violence against women in India is deeply disturbing, and if anything, now is the time for women to speak their truth, to not be afraid. Making this work was a transformative experience for me, hence the title. The work is more obviously about sexuality and desire, and brings up the female body as a site of conflict. In an interview for her new memoir In the Body of the World, Eve Ensler talks passionately about how women and girls become exiled from their own bodies, either through real or imagined violence. She says they become “desperate for a way home.” Many feminists have used the female body as starting point to investigate notions of freedom, and what it means. Ironically, I’m showing this work in New York, not in India. But making this body of work has emboldened me to take on bolder subjects, and I am not against showing work dealing with gender and sexuality in India.

Bed of Roses #2, 2013

Is there a queer community in Mumbai?

Yes, there is, and it’s very stymied by familial, social, cultural, religious and ethnic affiliations and restrictions in a patriarchal system that restricts women at every turn. I probably have more freedom not being embedded in an extended family and community structure, although being a single woman has its setbacks. There’s very few defined roles for women in that social fabric, and they include “mother,” “sister” (or some other female relation), or “whore” and “prostitute.” There needs to a massive rehaul of those identities if women are going to be allowed to thrive and prosper as individuals in that culture, straight or queer. And men need to be educated from a young age, not left to their own devices to figure it out. Still, it’s come a long way from when I moved there in 2006.

I have to keep reminding myself that New York is not a model for Indian cities. The latter carries an entirely different historical baggage, and gender and sexuality has to be viewed within those parameters. It may look repressive through Western eyes, and to a large extent it is, but people also find ways to exist and co-exist that can be surprisingly radical. I can understand that as an observer, but having had an entirely different formative process myself, I am still trying to find ways to participate in a meaningful and engaged way.

I read an original short erotic story about two Indian women that was socially and racially charged at an open mic session that was hosted by a queer organization in Mumbai at a popular restaurant last year. It made people uncomfortable, not for the erotic content but because it triggered deeply embedded hypocrisies around socio-economic status, caste, power and class. It also made me very uncomfortable to read it to an audience that wasn’t ready for it. I realized I need to think more about audience if I do something like that again.

Do you see yourself continuing to negotiate your gender and sexuality in India? Don’t you want to just be in a place that embraces that part of you?

I’m still figuring that one out, to be honest. Mumbai is also a place that doesn’t let me go. It challenges me, drives me, intrigues me and sometimes just plain frustrates me. I can’t say my life is hard per se; any place has its own set of challenges. I probably have the best of both worlds as I move between Mumbai and New York, and both represent “home” to me in very different ways. I am nurtured by these polar cities, and in that sense, I am extremely fortunate.

In an interesting way too, some of my internal dialogues about gender and sexuality have been recorded in the Indian media. Femina, which is India’s largest distributed women’s magazine, ran a feature story last year on women and their relationship to their bodies and they wanted to engage with interesting women from different fields who thought about their bodies differently from the norm. I am quite proud of it, and of Femina for being progressive enough to run it. I talked about cutting off my hair. Hair plays such a staple in notions of femininity in India; it’s treated almost as sacrilege if you lop off your locks.

In the end, life is only easy from a distance. When you get up close, it’s messy; and the deeper you go, the messier it gets. You have to make peace with the messiness. That said, I’m a human being and I desire many of the things that other people desire, like a permanent home, a stable relationship, the presence of a community, and so on. But I’m driven even more by my need to unravel appearances, to plumb deeper into the idea of selfhood. At least for now.

Comments (5)

Pingback: Sharmistha Ray, Growing Up in an Islamic Culture as an Indian Lesbian Artist | Sexuality in Art

Pingback: From abstraction to the vibrant female form: Fellows Friday with Sharmistha Ray | TEDFellows Blog