If your home had been devastated by a disaster, would you stay? Why do people choose to remain in potentially life-threatening places? These are just a few of the complex questions that photojournalist Michael Forster Rothbart and filmmaker Holly Morris explore in their respective work, documenting the lives of people living in Chernobyl and Fukushima. Of course, in order to do their work, Morris and Forster Rothbart had to live in contaminated zones themselves.

If your home had been devastated by a disaster, would you stay? Why do people choose to remain in potentially life-threatening places? These are just a few of the complex questions that photojournalist Michael Forster Rothbart and filmmaker Holly Morris explore in their respective work, documenting the lives of people living in Chernobyl and Fukushima. Of course, in order to do their work, Morris and Forster Rothbart had to live in contaminated zones themselves.

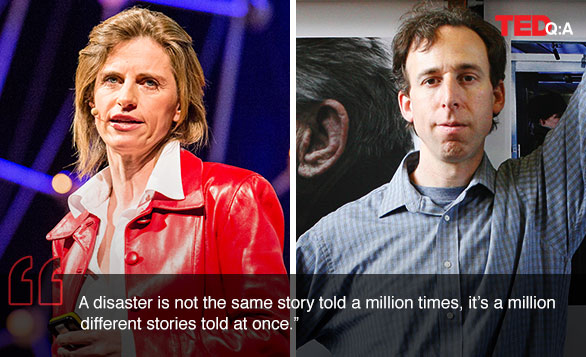

Holly Morris: Why stay in Chernobyl? Because it's home.

In today’s talk, Holly Morris describes a group of elderly women living illegally in Chernobyl’s “dead zone,” who she followed for the documentary film The Babushkas of Chernobyl. For more than 25 years, these “babushkas” have survived on some of the most contaminated land on earth, refusing to be evacuated from their homes. And in the brand new TED Book, Would You Stay?, Michael Forster Rothbart captures the unique lives of groups living nearby Chernobyl and then travels to Fukushima after the nuclear meltdowns there. This collection of images and essays documents his journey to understand the lives of people who, despite the danger, choose to stay. (Read an excerpt.)

Holly Morris: Why stay in Chernobyl? Because it's home.

In today’s talk, Holly Morris describes a group of elderly women living illegally in Chernobyl’s “dead zone,” who she followed for the documentary film The Babushkas of Chernobyl. For more than 25 years, these “babushkas” have survived on some of the most contaminated land on earth, refusing to be evacuated from their homes. And in the brand new TED Book, Would You Stay?, Michael Forster Rothbart captures the unique lives of groups living nearby Chernobyl and then travels to Fukushima after the nuclear meltdowns there. This collection of images and essays documents his journey to understand the lives of people who, despite the danger, choose to stay. (Read an excerpt.)

The TED Blog got these two documentarians together for a conversation about what drew them to these stories, and what surprised them along the way. Below, an edited transcript of the discussion.

Holly Morris: You spent two years in Chernobyl — not in Chernobyl, but nearby the Chernobyl community? Is that true?

Michael Forster Rothbart: Yes, I spent two full years living in Ukraine. Pretty quickly, I realized that I couldn’t live in Kiev and commute to the Chernobyl area, because there was just no way I could make that mental shift from living in cosmopolitan Kiev to understanding what life was like in these little villages. So I decided I had to locate myself there. I found a room to rent in a little village of 1,000 people, and that was basically my base of operations. You were in that general area too, right?

HM: Yes, I was there initially to cover the 25th anniversary of the accident. And I happened upon this group of women living inside the Exclusion Zone. They had returned to their ancestral lands shortly after the accident because, basically, they simply did not accept being evacuated.

MFR: I know you had a very successful Kickstarter campaign a year ago to work on filming these babushkas in the exclusion zone. So give me an update? Where are things?

HM: Since that campaign, I’ve been back to film in and around the Exclusion Zone two more times, trying to capture a story largely centered around the babushkas. Their numbers are dropping quickly. When I first started this story, there were 230, approximately, people living inside the zone, and now there are about 100.

MFR: I didn’t realize. Amazing. When I was there last, in 2009, it was 386 people.

HM: It’s really a very urgent story in that respect, that their voices are going away forever. And when they’re gone, the area won’t be re-inhabited by people — just animals and scientists, and zone workers. I’ve spent quite a bit of time over the last few years in the Chernobyl area covering this story. It’s a very tragic story, and a difficult one in a lot of ways, but it’s also one that’s infinitely compelling. Chernobyl is a story that’s continuing to play out. It’s not just history; it’s this long narrative. I’m wondering if you had that experience, too, and what you found compelling? What made you commit to a story like this for so very long?

MFR: I think my commitment really started when I was in Ukraine on a Fulbright.

I started poking my nose into things, and that’s really when I first understood what a wealth of different stories that people have there. I realized that, when there’s a disaster like Chernobyl, we only hear one or two stories over and over again. But a disaster is not the same story told a million times, it’s a million different stories told all at once. The photography I had seen prior to going to Chernobyl really distorted what was actually happening there. A lot of photographers, a lot of journalists, come in briefly expecting to find danger. And because that’s what they’re looking for, that’s what they photograph. But I felt like this wasn’t the full story. Focusing on the danger is sensationalist, and it hides the other, more complex stories about the communities of people who are there. And I think you probably discovered the same thing? Because you came in as a journalist, but then you realized that the reactor’s not the full story. The people are the really important part of the story.

HM: Yes, exactly. There’s the sort of sensational danger factor, which is obviously real. But it’s the longer term effects—the less sexy devastations—that are underrepresented. There’s such a human part of the Chernobyl story that isn’t often getting told, which I think is so fantastic about your TED Book. Could you talk a little bit about that? How the fallout from Chernobyl isn’t just about radiation?

MFR: Well, I think that people are affected very differently by Chernobyl, depending on both who they were and where they were at the time of the disaster. So there are the evacuees, of course, and everyone thinks about them. But then there are also the people who are living just across the fence. Radiation, of course, is not stopped by a barbed-wire fence. So there’s an arbitrary cut-off, Soviet-set, of what was considered contaminated and what’s not considered contaminated. But people just on the other side of the fence are dealing with all the same issues.

And then there are all the people who have — in Russian they call them “invalidov” — the people who’ve become sick because of radiation, not to mention all of the liquidators. There were at least three-quarters of a million liquidators — the veterans who were doing the cleanup.

But, as you know, it’s often not the radiation that has the biggest impact on people. It’s all the secondary issues — the health issues, but also all the economic issues, unemployment and disruption of community—which you talk about in your TED Talk. The fact that peoples’ whole lives have been uprooted, that they’ve been torn away, except for the few babushkas who are refusing to stay in the exclusion zone. Everyone else had their lives turned upside down. Well, I guess the babas have, as well. Still, what’s really devastating is that loss of community and loss of social support systems. You know, the UN report said that that had a bigger impact on people’s lives than the actual radiation, and I really believe that.

HM: The relocation trauma is something that, when I got involved with the story, really became the elephant in the room. All the babas inside the zone, and outside say, “Oh, if you leave, you die. I’d never leave my motherland.” This was their way of talking about relocation trauma.

MFR: In your TED Talk, I love the fact that you said that you personally are more attached to your laptop than to anyplace where you live. I talk about that in my TED Book too. I think that, as Americans, it’s hard for us to understand how deeply rooted people really are to their ancestral villages, because we move all the time. And so I think that, in this way, we’re making little destructions to ourselves every time we move. We’re ripping up those social networks that we have, and I think probably doing a lot of damage to ourselves and our society by moving all the time. And if it’s hard for us, imagine how it must be for people who have stayed in the same house for generations.

HM: I found that covering this story—in which the enemy or the obvious villain, radiation, is invisible—created a special set of challenges. This thing has infiltrated the realities of so many people, and—

MR: Radiation is hard to photograph.

HM: Exactly! You couldn’t see it, couldn’t feel it, couldn’t taste it. I’m wondering if that impacted your photography at all, or if the invisible enemy changed your relationship to your subjects, or made them a different kind of subject? I mean, if you are covering people who’d lived through a conventional war, it would be a different, teachable enemy. But we’re dealing with radiation, which is invisible. How did that impact your photography?

One of Michael Forster Rothbart’s stunning images from Would You Stay?—a group of three girls living in the Chernobyl area head to their prom. Find out more about reading this TED Book.

MR: You’re always looking for signs. I was especially aware of that in Fukushima because, in some ways, places like Fukushima City have already returned to life as usual. The majority of the people who live in Fukushima City were not evacuated, and yes, there was a serious earthquake, but the Japanese were pretty quick to tear down the damaged buildings. So as you drive around someplace like Fukushima City — unless you have somebody pointing out local landmarks — you miss the signs. I remember in Koriyama that there were all these temporary classrooms outside because the high school was too damaged to safely enter. But that’s earthquake damage; an earthquake leaves a lot more visible signs than radiation does. With radiation, you have to know what you’re looking for. I think that’s partly why my interest is really more in the people, and why my book is, in many ways, as much an oral history as a photography book. I spent a lot of time interviewing people and really getting to know them. In the Chernobyl area, I felt like I had a unique opportunity, not just take a snapshot of what people’s lives were like at any one moment, but to follow them over time and see how things changed for them.

HM: Speaking of that, you spent quite a bit of time in a relatively contaminated area. Did you have concerns for your own health while you were creating this book?

MR: I asked a lot of questions of experts when I was starting out, and I came to the conclusion that I might be slightly increasing my risk of cancer sometime in the future by doing what I did, but that any risk was relatively small. So it was worth it, to me. I have friends who are war photographers and go to places where they get shot at. Personally, that’s not a risk I’m willing to take. But with radiation, it’s all statistical probability, and so yes, I’ve increased my probability slightly. But I feel like I had to do it. I know for a lot of people who come to Chernobyl, when someone offers them a cup of tea or apples from their tree, they turn it down. But I felt like I couldn’t refuse somebody’s hospitality. Of course, when I had the choice, I would go to the store and I would buy the imported German jam, I wouldn’t buy the local Ukrainian jam. But if I was at someone’s house, I wouldn’t turn down their food. I’m sure you were in this situation, too.

HM: I think that being there is a lesson in relative risk. Also, there’s this idea about the spottiness of contamination. It was a nuclear fire that burned for all those days, not a bomb explosion where you could delineate the contamination. So this idea of the spottiness, and it not being very well tracked or mapped contributes to this reality that it’s just hard to be vigilant all the time, and know exactly when and if you’re taking in contaminated food or drink.

MFR: That’s really interesting. The United Nations and the Ukrainian government used to try to discourage people from berry picking and foraging for food in general because wild berries accumulate radiation more than other things. But they failed completely, because people were living a subsistence lifestyle in these villages. So then the UN printed this map that showed every square kilometer and the radiation levels in order to steer people to forage in places that were less radioactive. But of course, radiation is dispersed so randomly that even one kilometer at a time isn’t really detailed enough to know if this berry patch on this side of the street is better or worse than the one on the other side of the street. I think you’re right that psychologically — you just can’t be afraid all the time. You can’t live that way.

HM: Exactly. You can’t live on red alert. We, as visitors and journalists, are sort of on red alert, especially at the beginning. The people who live there—you recognize a difference in them quite quickly. It’s: We’re not thinking about this danger all the time. And then, even as a visitor or a filmmaker or photographer, your wariness about things disintegrates a little bit.

MFR: I think it’s pretty amazing. We’re so adaptable as a species that we can get used to anything, and that’s why there are people around the world living in such terrible situations. I think that’s definitely true in Chernobyl. In Fukushima, I feel like the radiation is still new for people, so they’re still figuring out how they feel about it, and how to relate to it. And some people, I think, their first impulse is just to flee. But then after a year or two living in evacuee housing, they start thinking, “Well, am I really better off living in this one-room apartment, or would I be better off going back to my farmhouse in the mountains and growing my own food?”

HM: An important factor in this conversation that gets left out: happiness. I believe there’s a great tie between happiness and health and so—this is not to dismiss the very real and very negative fact of radiation—but if you are relocated, and you are miserable not living the life you’ve always known, you become unhappy and depressed, and these things also affect your health. So it’s a strange equation that happens in the wake of these kinds of nuclear tragedies.

MFR: You just reminded me of this great scene in your film of these babushkas walking together, merrily singing on a rural country road in the exclusion zone. That scene really captures a little bit of the joy of everyday life. And yes, you’re right that when people focus on all the negatives: the cancer, and the contamination, and the fear, they forget the other half of what life is all about.

HM: I think that’s very true. I do have to ask you, after all the experience you’ve had, and the years you’ve spent in these places, would you stay?

MFR: That’s a really hard question, and I struggled with it for a long time. Even when I was writing this book, I was still struggling with the question. And actually in my first draft, my editor said it wasn’t good enough, that I had avoided really answering the question. So I thought back to an experience I had when I was in high school. There were these old farm fields behind my parents’ house that I loved to play in as a child. You know, we’d go exploring and ice skating there. Then it got developed into this ugly, suburban tract housing bordering my parents’ backyard. And of course it doesn’t compare at all to Chernobyl, but I was really affected by it, and for a few years I couldn’t stay there because every time I went in my parents’ backyard, I got very upset at everything I had lost.

Based on that personal experience, I think if there was a nuclear accident nearby, I think I would leave. But unlike most people, I’m not sure that it’d really be the radiation that would make me leave—obviously, that would depend on how bad the contamination was—but I think it would be the pain of having to look every day at what I had lost. Those babushkas living in the Exclusion Zone, they’re having decent lives, but on the other hand, they’re the last two people or the last eight people in their villages. And that life is really like a ghost of what they once had.

And the same is also true in the villages where I was living, in Sukachi. In some ways it’s a comfortable, fully-functioning village, and people go on, but it’s definitely not the same place it was before the accident. Because there are no jobs, there’s not hope for the future, you know? The children graduate from high school and they leave, because they don’t see any future for themselves in these little farming villages.

HM: The one part of the story that often gets lost is how the culture of the Polesia region, this very special culture of this part of Ukraine, was also wiped out by Chernobyl. As the older generation dies, what’s left of that culture will really be gone, because these areas won’t be robustly re-inhabited.

MFR: I feel like that happens all over the world with modernization.

Holly Morris introduces us to some of the women who still live in the immediate Chernobyl region. Watch her TED Talk.

HM: Let me ask you, since you’ve spent both time in Fukushima and Chernobyl: Chernobyl happened 27 years ago, and Fukushima’s still playing out. What are the lessons to learn from Chernobyl, and are they being taken on board in Japan?

MFR: The short answer is no, not at all. I think the Japanese actually had a unique opportunity to learn from the mistakes of Chernobyl, but they really didn’t. And so the disaster management was terrible in Japan. Hopefully, the mitigation stage will be better. But when they were evacuating people in Japan, they kept changing how big a radius they were evacuating. Local government was telling people different things than the national government was. I think that mismanagement is part of the reason that the Japanese have really lost faith in their government. And they also felt that they were lied to—that the Japanese government wasn’t telling them the truth about the danger.

I think the confusion was partly the Japanese government’s fault, and partly outside forces like the International Atomic Energy Agency. The U.S. government was telling people to evacuate 50 miles away from Fukushima, whereas the Japanese government was telling people 10 kilometers, 20 kilometers. And so the Japanese started to wonder, “Why is the U.S. government telling all the people to get 50 miles away.” It turns out the Japanese were more correct than the U.S. government in terms of how far the danger had spread. But once people lost faith in their government, there was no way for the government to get it back.

It’s interesting to think about the political implications. The same thing happened in Chernobyl: People felt misled, and there was an environmental movement that rose up in the former Soviet Union after Chernobyl, partly in response to it, and in response to people feeling like the government weren’t taking their health and environmental concerns seriously. Some people say that that’s what ended the Soviet Union, that it as the nail in the coffin.

In Japan, there are political implications, as well. For instance, Japan is talking about ending nuclear power. But I think we will see these implications—not just for the local people, the 83,000 people who have been evacuated from Fukushima—but also for all of Japan, we’ll see political implications for years to come, just as we did in Ukraine.

HM: I talked to some Ukrainian officials who told me that they were offering their help—their expertise and experience—when Fukushima started happening, and basically were rebuffed. That Japanese were not interested in what they had to offer.

MR: I heard a slightly different story, which may or may not be true, which is that the bureaucrats were rebuffed, the Japanese didn’t want Ukrainian bureaucrats — but they did want Chernobyl workers. I heard that from a Chernobyl worker, so I don’t know for sure if it’s true or not.

HM: What do you want someone to take away from your book? It’s been a huge investment of your creativity, your time and your passion, and I’m interested in knowing what impact you hope it will have.

MR: I really hope that people reading this book will both be moved by some of the personal stories of people I interviewed, but also start to think differently about disasters, and how we treat disasters. Because people always say things would be so much better if the Chernobyl accident hadn’t happened, or the Fukushima accident hadn’t happened. But disasters are always going to happen. If it’s not a nuclear accident, there are plenty of other natural and human-made disasters. And the real question to me is: How can we manage them better? Tragedies will happen, but if we’re better prepared to deal with the consequences, there would be a lot less suffering. So that’s what I hope.

There’s this photo editor, Howard Chapnick, who said that photojournalism has not stopped wars, eliminated poverty or conquered disease, but neither has any other medium or institution. I’ve realized that my work isn’t really about change but about reflection and reconciliation. I’m sort of holding up a mirror for people. For instance, my first big Chernobyl exhibit was actually in Ukraine. I brought it right to Slavutych, to the city where the Chernobyl workers were living. And that was really exciting to me. For people to be able to see themselves and their neighbors reflected in a photography exhibit, and to think about their lives.

HM: What was their reaction?

MR: They were really excited. Because the people who are still working at Chernobyl don’t see themselves as heroes. But I do. I think I conveyed that to them through my photo exhibit. For them, it’s a job — it’s a life. But you know, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant is still a dangerous place. If the new safe confinement isn’t built, the sarcophagus is in danger of falling down eventually. So the people who are working there are really protecting the rest of the world from that danger. By having my photo exhibit right there, in the community, I was able to show people the way that I saw them: as heroic.

Then last year I took my exhibit to Vermont, where the whole state of Vermont was arguing about whether the Vermont Yankee power plant should close, or should get re-licensed. So my Chernobyl exhibit was in Brattleboro, which is six miles away from the power plant. But a lot of people in Brattleboro had never gone that six miles down to see their own power plant. So I had this exhibit where people attended from both sides of the issue—workers from the Vermont Yankee plant, as well as environmental activists—and we had this sort of public forum. First we talked about Chernobyl, and people looked at my pictures, but then we talked about their own local issues. It was so exciting to see these environmentalists and nuclear engineers sitting down and talking, probably for the first time, and finding common ground. And as I was watching them, I realized: this is the purpose. This is why I am doing this work.

HM: Don’t sell yourself short, Michael. You may well be changing the world then.

MFR: I’m not changing the whole world, but maybe I’m changing attitudes in Brattleboro, Vermont. When will your film be released?

HM: We’re hoping to release the film in 2014. We’re right on track for that, and it’s going really well. We will be able to share it with the survivors, which we’re grateful for. Throughout, we’ve always kept in touch with the ladies of the zone, who have been pretty spectacular over the few years we’ve been filming them, and we’ve grown quite attached to them. And even though they’re quite isolated, we try to keep them updated, and of course, look forward to bringing back the film to show them just as soon as we can.

MFR: I love that photo of Hanna Zavorotnya holding a copy of your magazine article. That’s a great picture. You, like me, continue to keep in touch. So, a question for you then: I know often, locals roll their eyes at journalists when they come in for a day and they’re all nervous about the radiation, and don’t get the story right, and don’t speak Russian, and are always checking their dosimeter, and they just want to get out as soon as possible. And I feel like you started out that way, but you made a choice to remain there. So I’m curious: Why did you stay?

HM: I did start out that way. But very quickly it became clear that Chernobyl is, above all, a human story. It’s not just a story about radiation. And the fact that there were these fiery women who insisted on returning to their ancestral homes inside the zone, and they now live there and support one another, and it’s this unusual kind of sisterhood of people who are alone together. Radiation or not, they’re at the end of their lives. So if their story wasn’t captured, it was going to go away and never be preserved. And so that’s really what motivated me. While we were always sensitive to the radioactive issue when we’re there filming, it really became about the people.

They’re such a special group of people. They’re quite marginalized. Not only are they there semi-illegally, but they’re old ladies in Ukraine, you know? Not actually listened to all that often, I think. You lived there longer than I did, so correct me if I’m wrong, but I just really felt their voices mattered. And not only are they having this unique experience inside the zone, but they’ve lived through the worst atrocities of the 20th century, in terms of Stalin and the Nazis and Chernobyl. So they have a lot to say. We wanted to capture that before they were gone forever.

MFR: I had more than one elderly person tell me, “Oh, Chernobyl’s not so bad compared to World War II.”

HM: Exactly. I mean, they were not about to flee in the face of an enemy that was invisible. You know? They’ve been through bullets zinging by their heads, and lots of atrocities, so they’re like, “Whatever. I can keep going on with my life the way it is. I’m not leaving. “

MFR: On the other hand, I also heard people in Chernobyl refer to Chernobyl as ‘our war.’ Which is interesting. So let me ask you: Do you feel protective of people you met and interviewed? Like you want to be sure that others, in the future, get the story right?

HM: I don’t know that there’s anything I can do to protect them, other than try to tell the truest and most authentic story that there is about their lives — the full reality of their lives, not just the handy headlines for journalists. And if we tell the best and truest stories, and let them tell their own stories, then I think that’s the best we can do, and hopefully that is the version that will rise to the top, and that will be what’s heard by the world. I’m just really grateful that your book — and hopefully our film — will tell the deeper, longer, more nuanced story.

Comments (6)

Pingback: Buy Steroids USA

Pingback: Chernobyl is home. – Foto[GEN]ERELL

Pingback: Tschernobyl ist Heimat. – Foto[gen]erell