Did you know that across the United States, cameras are automatically taking pictures of your car’s license plate as you drive by, recording your plate number and your locations over time? In a chilling talk given at TEDGlobal 2014, civil liberties lawyer and TED Fellow Catherine Crump called attention to the ubiquity of mass surveillance technology currently being deployed without public awareness, laws governing its use or privacy policies regulating what happens to the data being collected. (Watch the talk, “The small and surprisingly dangerous detail the police track about you.”)

Did you know that across the United States, cameras are automatically taking pictures of your car’s license plate as you drive by, recording your plate number and your locations over time? In a chilling talk given at TEDGlobal 2014, civil liberties lawyer and TED Fellow Catherine Crump called attention to the ubiquity of mass surveillance technology currently being deployed without public awareness, laws governing its use or privacy policies regulating what happens to the data being collected. (Watch the talk, “The small and surprisingly dangerous detail the police track about you.”)

Crump tells the TED Blog more about her work, and the technologies that are quietly threatening the privacy and civil liberties of innocent people.

You are a civil liberties lawyer with many different strands to your work, but in the talk you gave at TEDGlobal, you focused on automatic license plate reader technology. Why did you choose that topic?

I think it is commonly understood now that the National Security Agency is engaged in the mass surveillance of entire populations. But I don’t think people realize that local police departments often have very powerful mass surveillance technology as well, and I wanted to be able to focus attention on that. At the moment, many people don’t understand this technology, its ubiquity and how it’s being used. People often don’t realize that if you drive a car in the United States, you’re most likely being tracked by license plate readers, and that photographs of you are being taken and stored on a regular basis.

How does it work, and what’s it for?

The license plate reader takes pictures of every passing car, stores the photographs, and converts the plates into machine-readable text to extract the license plate numbers. That plate number can be checked against a hot list of cars — for instance, cars associated with someone who’s wanted for a crime. That part is unobjectionable. It’s good for the police to be able to automatically tell when a car goes by whether it’s been stolen, for example.

The problem is when law enforcement agents then engage in the mass retention of all the plate data the readers collect — whether or not it pertains to people who may be involved in wrongdoing. You end up with what is essentially a massive tracking database that gathers information about innocent people. The vast majority of us are innocent. Allowing the government to collect massive quantities of information about everyone opens the door to abuse.

A City of Alexandria police car equipped with mobile automatic license plate readers. mounted on the trunk. Photo: Something Original

But what could anyone really do with that information that would hurt us?

That information can be abused in a number of ways. Where people go is very revealing. In most parts of the United States, you cannot get anywhere without driving a car. So if you want to go to your therapist or an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting or to church, all your movements can be tracked. And your movements reveal the types of things you value.

Another reason for concern is that the government has abused information about private citizens in the past, to engage in surveillance. I’m thinking specifically of J. Edgar Hoover, under whom the government collected personal information and used it for political purposes. Unregulated data can be used for political reprisals, for blackmail, or even for simple voyeurism. That’s not something the American public should tolerate.

Traditionally we live in a government of limited powers, and the idea has been that the government only investigates people when they are suspected of wrongdoing. Technology like this almost reverses the presumption and tracks everyone just in case the information may be useful someday. I don’t think that’s in keeping with the limited view of government power that we’ve traditionally had.

Realistically, what can we do?

I think one problem is that often, even local city councils doesn’t know that their police departments have acquired this technology. At the very least, we need rules that say if you’re going to acquire a surveillance technology, local government needs to know about it, and there should be policies in place that govern how it can be used.

In the case of automatic license plate readers, the good news is that it would be fairly straightforward for policies to allow fair use of the technology for law-enforcement purposes while simultaneously protecting people’s civil liberties. That’s why I think it’s useful to focus on this issue. It can be win-win for everyone.

Is there evidence at this point of wrongdoing?

It would not surprise me if this data had been abused, but the thing about secret government surveillance programs is that abuses often don’t come to light. I will say that there have been uses of it that are quite troubling. For instance, the New York City police department has driven cars equipped with automatic license plate readers past mosques to report every attendee. And in the UK, the police put an individual named John Catt on a hotlist. He got pulled over when his license plate was hit because he’d attended dozens of political demonstrations. He generally sat and sketched the attendees. But as he’d been to a large number of events, it seems to have triggered suspicion.

There are many other ways this technology could potentially be abused. You could set up a license plate reader outside of a newspaper office to see which police officer is there giving a tip about wrongdoing, for example. You could research where a rival political candidate has been, just to see whether they’re doing anything that could be used to get dirt. The more mundane and common form of abuse would be, say, the police officer looking at the ex-girlfriend to track movements.

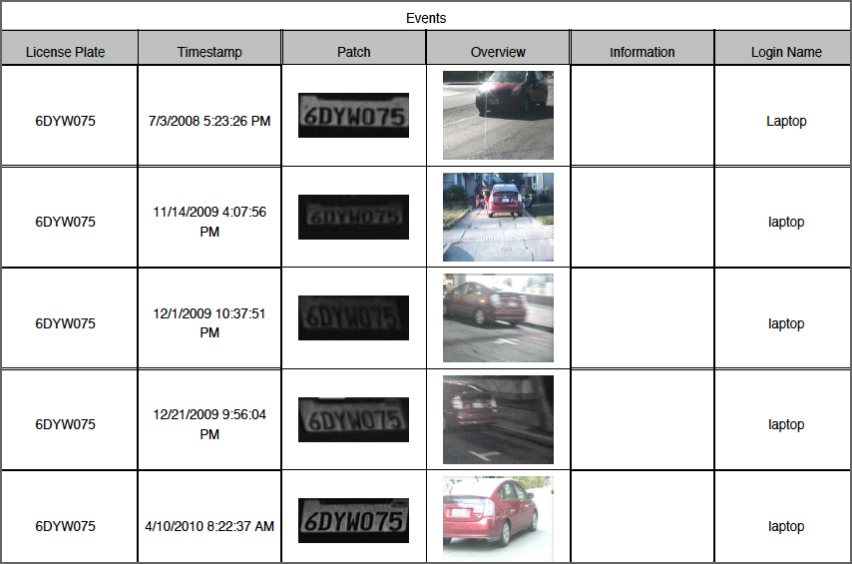

An example of the data plate readers collect. Note that photographs may include visible images of passengers. Image: public record, supplied by Mike Katz-Lacabe

How did you get interested in the subject of mass surveillance?

I went to Stanford Law School in September 2001, and on what was meant to be my third day of classes, September 11 happened. The following month, the Patriot Act was passed, radically overhauling the laws of surveillance in the United States. I happened to be sitting in a law school with a lot of renowned constitutional experts, so it was impossible not to be both fascinated and alarmed by the legal developments of that time.

Until then, my goal had been to provide legal services to people who wouldn’t otherwise have access to them. But that moment got me interested in the privacy context. In 2002, I began working at an organization called the Electronic Frontier Foundation, where I spent the entire summer trying to answer the legal question of whether the government could compel internet service providers to log all of the internet usage records of their customers. The fascinating aspect of these laws was that they were so up in the air. It’s really not clear what free speech and privacy laws should apply to the internet. Every time there’s a new communications medium, there’s a great debate about how it ought to be regulated.

After law school, I went to work for the ACLU and focused more on internet free speech issues.

Who were your clients?

I represented high-school students and a teacher suing schools in the state of Tennessee, because they’d installed internet-filtering software that blocked access to pro-gay but not anti-gay websites. One of the students was trying to research scholarships available to LGBT youth, and couldn’t access the website because it was blocked by the school as inappropriate content for minors. But she was able to access websites about reparative therapy and other debunked practices that people claimed “cure” people from being gay. Being able to represent kids facing that kind of discrimination was really moving for me — and we won big. It’s not just that we won in one or two schools, but it was a huge number of schools across Tennessee were engaged in this discriminatory blocking, and our lawsuit fixed it.

I then represented a lot of plaintiffs challenging a broad-based internet censorship law called the Child Online Protection Act. Congress had passed a law forbidding putting speech on the internet if it was “harmful to minors” — without clearly defining what that meant. So, for example, we represented Urban Dictionary, which provides definitions for slang terms. We represented Salon magazine, who’d published the photographs of the Abu Ghraib prisoners being tortured in the nude. Salon was legitimately concerned that they could be subject to prosecution or fines under the statutes.

Above, watch an ACLU video about its case addressing LGBT nonprofits being blocked by Tennessee schools.

It was rewarding to be able to do that type of work, but I eventually I decided I wanted to do privacy work — a really important battle, but a much tougher slog. So I filed lawsuits, for example, challenging the government’s policy of engaging in purely suspicionless searches of laptops and other devices at the international border. The government argues that when you cross the border that it can search your phone, your laptop, for any reason. Or no reason at all.

They can? What are they looking for?

Everything from evidence of a terrorist plot to illegally downloaded MP3 files. Now, if your laptop or your phone were sitting in your house, it’s very clear that the government would need to get a warrant to conduct a search. But they argue that because you’re coming across the border — where, to be sure, the government has a stronger interest in preventing contraband — they have the right.

Is this something we should all think about when we travel?

As a lawyer, am extremely cautious when I travel internationally, particularly because I often represent clients who are themselves suing the US government, and I feel it would be irresponsible for me to expose those files at the border. So I have a separate computer that I use for international travel, and I don’t take my main computer. And I use encryption. If you don’t want the government to be able to look at what you have on your computer or phone, you should seriously consider doing this, or write over your information before you cross the border. It’s actually not very difficult to encrypt your electronic devices.

With your education and background, were you surprised when the NSA’s surveillance activities were revealed?

I was surprised. It’s not that you couldn’t, if you’d been paying very careful attention, guess what the government might be doing. But there’s a huge difference between being on the outside and engaging in speculation and conjecture, and being able to demonstrate to the American public that something was actually happening. So the revelations were huge, because people didn’t understand that all of their telephone calls are being logged, or even that the United States had the capacity to, for example, record the content of every telephone conversation in a small country.

Few people realized just how far beyond anything that had been recognized as legal previously the NSA programs were going to go. This wasn’t just a minor extension of what courts had previously approved. It was unlike anything anyone had ever seen before, in scope and the type of information gathered. I understand why Edward Snowden, seeing all of this from the inside, would feel very strongly that it was something that the public ought to be aware of, to the extent that he was willing to take such great personal risks in order to do what he’s done.

An automatic license plate reader, fixed on a pole. Photo: Jay Connor, Tampa Tribune

Is this how you got back into working on government transparency and accountability?

I was involved in a few lawsuits suing the NSA for the mass collection of the telephone numbers Americans dial. The first program that Edward Snowden revealed was a program in which the government records every phone number people dial, and the date, time and duration of the call, within the United States. It was particularly bold for the government to do that within the United States, because that’s where constitutional rights apply the most strongly.

The ACLU itself was a phone customer. Even knowing who calls the ACLU can be significant — say a government whistleblower calls. So I was involved in litigation essentially arguing that this was not a reasonable search under the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures.

I’ve also worked to increase the amount of transparency around surveillance programs by making large-scale use of public records laws. Every state has a law that essentially says you can file a request to the government to get access to government records. At the ACLU, we filed some 600 public records requests with police departments in 38 states to learn about how they were using this technology, and what they did with all the data they gathered. That project netted 15,000 pages of records — and analyzing those created new knowledge about how this technology was being used, allowing us to reveal to the public for the first time that these devices were deployed in police departments big and small all around the country, often under circumstances unconstrained by privacy policy.

What are you up to next?

I recently left the ACLU and am a clinical law professor at Berkeley Law School, so I work with a small number of students on cases and projects for clients. Because it’s a law school clinic, it has a public interest mission, and one aspect of what we try to do is to provide legal representation to individuals who wouldn’t otherwise have it.

Back to your original goal.

Exactly! So I would like to continue representing plaintiffs who’ve had their rights violated by surveillance. The thing is, if you think your constitutional rights have been violated and get involved in a civil case, you’re not necessarily entitled to a lawyer. And most lawyers who have expertise in surveillance work for the government itself, or for large telecommunications companies, not individuals. I hope to change that.

I would also like to find a way to partner with investigative journalists to keep doing the public records work, to reveal more about mass surveillance. Automatic license plate readers are probably the best example of such technologies, but they’re not the only one. I think it really serves the public interest to know what our government is doing in our name.

Comments (8)