In Floating Peep Show, audiences were ferried across the San Francisco Bay to four sailboats rafted together, where they paid to watch live performances in the hulls. Photo: Constance Hockaday

Constance Hockaday makes large-scale installations on open water. Identifying as a Chilean-American queer artist, Hockaday creates spaces that celebrate creative freedom and counterculture communities while defying gentrification. Take the Floating Peep Show — in which out-of-work drag queens and exotic dancers performed in the hulls of sailboats in the middle of San Francisco Bay. Now, Hockaday plans to turn a retired Coast Guard vessel into a venue for a huge waterborne multimedia spectacle. Always Get on the Boat will both celebrate and mourn the likely demise of the Fifth Street Marina — a longstanding alternative community on a post-industrial waterfront in Oakland, California, that is slated to be overrun by commercial development.

As she sets the plans for this new work, we talked to Hockaday about the struggle to make space for alternative culture, and why urban access to open water is so important.

In your talk at TEDGlobal 2014, you described the Floating Peep Show, and how it was inspired by two San Francisco counterculture establishments that had closed within months of each other — the Lusty Lady and Esta Noche. Tell us more about what these were.

The Lusty Lady was the nation’s only worker-owned, unionized adult entertainment business. It was a peep show, so you looked through a window at women — and people of actually many different genders, body shapes and looks — and you look at them without their clothes off, or erotic dancing. It was an institution, and it was located in what was known as the Barbary Coast. It felt a part of the old San Francisco, maybe one of the last places that felt like it was connected to that. It catered to the general public and also specifically to feminists, queers and radical sex culture, as well as kink and a very counterculture underground scene that’s played a huge part in the shaping of San Francisco. They shut down this past year.

Then, six months later, so did Esta Noche, a Latino gay bar in the Mission. It was spectacular, very special. It provided a place for gay Latinos who didn’t necessarily have a place in white gay-man world or in Latino culture. Everybody was welcome — it was like a queer Quinceañera every night.

Why did they shut down?

It was partly because clientele had moved out of the city because they couldn’t afford to be there. Social networking has also changed a lot of the way that queer culture interacts with each other. But these were cultural institutions.

So I rafted together four sailboats, and each one was a performance space. I contacted a bunch of Lusty Lady alumni, a bunch of drag queens from Esta Noche, as well as DJs and people from the Center for Sex and Culture. I hired them for four nights to perform inside the hulls of sailboats. We built a wall so that you couldn’t actually walk all the way into the boat: you could just step in. There was a money slot, and you could pay to see the performers. I told them to do whatever they wanted. Some of them did sex shows, some of them did strip shows, some of them did karaoke shows, some of them did super high fashion.

We picked people up in small inflatable boats, and transported more than 600 audience members across the San Francisco Bay to the sailboats in four nights. One night we did it near Dogpatch, in industrial San Francisco, and then three nights we did it in Clipper Cove, on Treasure Island. Everybody was there: all the old, curmudgeonly sailors who were all in charge of the sailboats, plus sex workers, drag queens, friends, art dorks, pervy kink dudes, tech kids. All hanging out in the middle of the water on these boats.

This was great, because it can be lonely and frustrating and confusing to be an artist in a place where artists are losing real estate, and losing a way to survive in that role in society. It’s hard enough to be an artist in general. It’s a scary life path to choose.

A customer takes in a peep show being performed in the hull of a sailboat. Photo: Constance Hockaday

There’s so much going on in your work — gentrification, changing urban landscapes, water as public space. Is this all something that you set out to do, or did it all just happen?

Oh my god, no. I tried really hard not to do it, for a long time. I didn’t want to be an artist! It’s a total pain.

Really? What did you start out doing?

I did everything possible. I have three degrees: an undergraduate degree in community development, a master’s in conflict resolution, and a master’s in fine art. I wanted to do something important, that would change the world. I was going to be a pediatrician, then a psychologist, then an eco-design architect, then a city planner, and then alternative dispute mediator. I did a lot of work with indigenous communities living in low-intensity war zones in Mexico and Central America, working for media justice.

But the one thing I know for sure is that I really love the ocean. I just want to interact with the ocean on my own terms. It’s beautiful, and it calls to me spiritually, but it’s also a space that is a no-man’s land. It’s upholding some other value system. In maritime law, you can move in whatever direction you want. Private property does not dictate your trajectory. It is a self-directed process, and you are in participation with nature and the shapes that the water is making.

So that, to me, is really important. It’s convenient to call it art, but I don’t know if it’s really art. It’s just what I do. I want to get people on the water in boats, and I want to tell a really good story. So I work with boats, making worlds on the water because I feel people behave differently, interact with each other differently there. I’m interested in getting people into a place where they can find some reverence.

Constance Hockaday speaks about the Floating Peepshow at TEDGlobal 2014. Photo: Ryan Lash/TED

And now you’ve launched a Kickstarter campaign for your next project — which celebrates another marginalized community that lives on the urban waterfront. Tell us about that.

Always Get on the Boat is a participatory community art project with a group of sailors and artists that are losing their place on a piece of land, which is connected to a marina, in Oakland, California. The Fifth Avenue Marina is a very special piece of property that artists and sailors have been building out — little nooks and studios, workshops, metal shops, with a very Cannery Row kind of feeling. It was an old industrial foundry that shut down. It got re-purposed around 50 years ago, and the owners of this property have allowed people to inhabit it and create spaces that fit their very specific creative needs.

Is this a cohesive, established community?

It’s established, but it’s also been very secret. It has been on the outskirts of the city in this industrial wasteland, and it’s been a free-for-all for many decades. And what’s really special about it is that it has had many decades to evolve and grow, and make itself into this world. There aren’t a lot of places in urban areas — especially in California — that are given that much time to just see what people with limited resources and a lot of really great ideas can build.

All of the land around the studios and the Marina is public trust land, and it’s also a Superfund site. People have been working for decades to figure out how to utilize this land in a way that is best for the public. People spent 10 years writing a plan for the estuary. However, there’s another contingency that is trying to change things so that the public trust land may be developed for private homes.

To make a long story short, development of private condos on this land is now set to go ahead, and they will be the largest buildings in Oakland. People will still have access to the water — but via mall boardwalks. And while the Marina community is not yet slated to be bulldozed, it will be developed around. That means that at any moment, somebody can roll up in there and be like, “That’s not up to building code. It’s going to cost you $5 million to bring this up to code.” And that will be the end.

A big part of the Marina community’s original ties was from fighting this development project the first time, and now everyone there is super depressed. So I thought, “Let’s do a project, something that’s going to bring everybody together so we can talk about what there is to celebrate in this place, as well as express the grief and the trauma of losing it.” There are old men — 80-, 90-year-old men — that have lived there for most of their lives. I have no idea, if they get kicked out, where they will go.

What will the project look like?

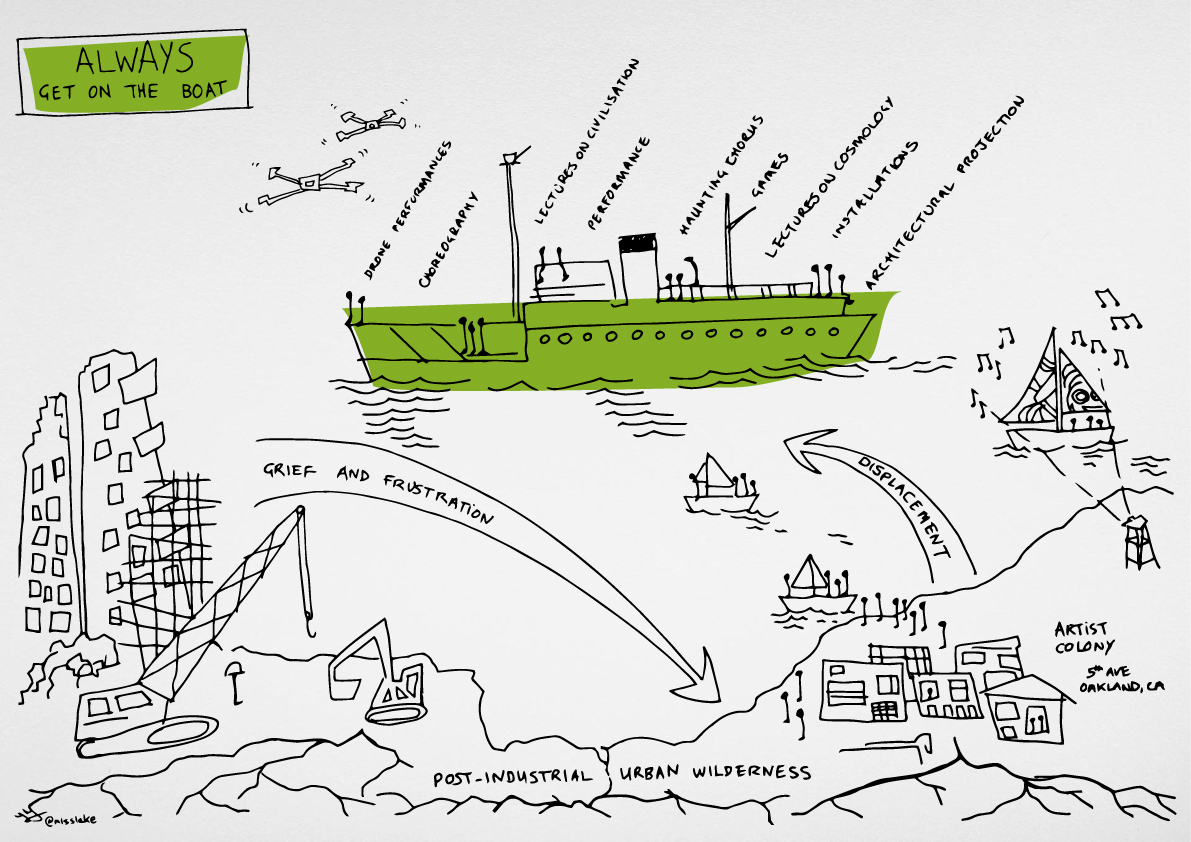

I’m getting a retired Coast Guard vessel — a 175-foot long, 1939 Coast Guard cutter called the Fir, and we plan to do an immersive performance inside and throughout the ship. The audience will be taken by boat to the ship, as we did with Peep Show, and then allowed to roam free. As they’re going through, different artists and sailors will perform. There’s a choreographer, and we’ll have drone operators and projection mappers. It will be a performance spectacle that allows the community to confront and process the grief and the frustration and the feeling of disempowerment that is coming with all of the changes — as well as celebrating itself.

While this will be quite far out in the water, the hope is that the Marina and development will be in view. We will be using drones and light to close the gap, so people can witness their landscape from another perspective, and multimedia will close the gap between the audience and the landscape.

A diagram of Hockaday’s proposed project, Always Get on the Boat, a waterborne celebration of the Fifth Street Marina community in Oakland, California. Image: Julie Freeman

Is this project partly about advocating the protection of public space?

Yes, but it’s also specifically about access to the water. It’s about having a relationship with the water. Not just walking on a boardwalk at a mall looking at the water, but being in participation with it, whether it’s recreationally, or for food, or for stewardship.

Different urban areas have different relationships to their waterfronts. In Santa Cruz, California, for example, public staircases go down the sides of cliffs straight into the water for the surfers. But in New York, people have been conditioned to understand the waters as a place of industry. Now all of that industry is coming down and the waterfront can be reinterpreted, but there’s been a century of no relationship to it. So people aren’t even imagining how to use it in any other way.

This is why, to me, a waterfront is so important in an urban area. There is a wilderness and spirit that I feel is important for the survival of all of humanity. The Fifth Avenue Marina has direct access to the water, in whatever crappy boat or whatever makeshift thing you have. You get in the water, and there’s this whole wilderness just right off the shore of the city. I’m not just talking about the seals, egrets and other creatures. I’m also talking about weather and a power of nature that is greater than the hand of man.

Would the ship be a permanent installation?

It will be temporary, but then — who knows? A museum in Santa Cruz is asking for it once we’re finished, and we might bring it back down the coast to Monterey Bay. I’m hoping to partner with museums and the Exploratorium, and we could technically take it on tour. But one thing at a time.

I’m also interested in collaborating with the tech industry, which is booming in San Francisco again. It’s frustrating, because there are a lot of really creative, socially conscious, wonderful people who are a part of that industry, who are sort of the face what is changing the city. I can’t help but feel pissed off at them, which sucks, because I love Google, right? I think it would be interesting to find ways to really make relationships with those people who innovate: the drone people, the people who are innovating with LEDs, and so on. I use technology more and more, and it would be cool to bridge a gap between what is happening in the tech world, with artists that feel like they’re being displaced by the tech world.

Apart from the technology, there’s another part of my practice that’s very much about video and storytelling and weaving all my ideas together. In the ship, there will be room for all different kinds of lectures. I want there to be a section of the ship that’s the story of the universe, and a section of the ship that’s the story of civilization. My hope is that the audience will be there for around three hours. There will be rooms where they can take sanctuary, and then go back out and take more information.

Why the story of the universe?

Because the story of the universe is really important. The sun is burning up right now, and eventually it will burn up completely, and then we’ll all die. That’s the trajectory of the planet. I think that’s important to keep in mind.

Yes, I’m sad about the general trajectory of how post-industrial American cities are developing, destroying all creativity and texture, as has happened in San Francisco’s gay bars, sex clubs and all of this radical culture. The same thing happened in New York. Maybe these cultures got a decade or two — maybe three, with momentum — to build a place. And then they are stamped out by completely sterile, contrived architectural realities that diminish the complexity of culture.

But having said all that, it’s also true that everything has to change and die. We can’t get stuck in nostalgia forever. We sort of have to get in line with what’s going on in the universe. And this is not a brand-new story. San Francisco is a boom-and-bust town. All of civilization has been on this path, and that’s important to keep in perspective.

.

Above, watch Constance Hockaday’s video introducing Always Get on the Boat, and visit Kickstarter to help make it happen.

Comments (3)