Filmmaker Jerry Rothwell films a family in Korakati, India. He is making a documentary that tells the story of the School in the Cloud. Photo: Courtesy of Jerry Rothwell

British director Jerry Rothwell, the winner of the first annual Sundance Institute | TED Prize Filmmaker Award, has spent the past year trailing TED Prize winner Sugata Mitra as he sets up the first locations of the School in the Cloud. Traveling between a remote village in India and a forward-thinking elementary school in the U.K., Rothwell has watched Mitra, a Newcastle University professor, plant the seeds of his global education experiment that lets children learn on their own, and from each other, by tapping into online resources and their inner sense of wonder.

The subject matter of School in the Cloud is definitely different from Rothwell’s previous films, which include Donor Unknown, about a sperm donor and his many offspring; Town of Runners, about an Ethiopian village famed for its athletes; and Heavy Load, about a group of people with learning disabilities who form a punk band. But Rothwell says he has long been interested in education and technology, so was up for this challenge.

School in the Cloud is slated for release in April 2015. Now that Rothwell is halfway through the project, we thought we’d check in with him to see how it’s going …

What’s the thing that you hear Sugata say the most?

Sugata’s mantra for adults is “don’t intervene.” That’s both really interesting, and challenging. Sometimes it’s the most challenging thing I find about the work. A month ago, I was at the new lab in Chandrakona, India, which just opened, and I was filming kids who’d never used a computer before explore one for the first time. There were four or five of them around this computer and they’d reached an error message where to them it seemed frozen. In fact, all they needed to do was click “OK,” but they couldn’t figure that out. I watched them for 20 minutes, wanting to intervene and show them that simple step, but because Sugata’s whole philosophy is that you can’t intervene, I didn’t do anything. His research suggests that when children find out things for themselves — and start showing what they’ve learned to other students in the room — they are going to retain it much better than if someone just comes and sorts them out. It’s difficult for someone in a teaching role, but I think he’s right.

Students at the School in the Cloud in India excitedly figure out how to use a computer. Photo: Courtesy of Jerry Rothwell

Some critics find Sugata Mitra’s ideas around ‘minimally invasive education’ radical. What do you make of the controversy around Sugata’s philosophy?

I think there is a tension between the rhetoric around his work and the work itself. Take for example the idea of self-organization, which is at the heart of the project. A great deal of organization of various kinds goes into making the work effective — so the question of what constitutes ‘self-organization’ depends on which part of the process you’re looking at. In some ways, Sugata is a provocateur. He strips educational processes down to something very simple and pure in order to challenge the way we do things. I think some of the opposition to his work doesn’t take account of the need for that provocation, and the context of it.

This is a global project. How did you decide what and where to film?

Very soon after I got the award, I traveled with Sugata to [India] with the idea of choosing where we would base the film. The project is spread in many different locations, but I wanted to go deep rather than wide, and try to look at the impact of these ideas in detail with a very few people: one family in a very remote Indian village, one “Granny” in the UK, one teacher in a primary school in the northeast of England. Fairly quickly, we decided to focus on the little village of Korakati in the Ganges Delta, primarily because it was the most remote place Sugata was working in, with no Internet or electricity. If the ideas work there, they will work anywhere. There are so many practical issues. To get there, you have to drive for three hours, take a boat down the Ganges and then hire a rickshaw to take you along a bumpy brick path for an hour or so. To build there, they had to carry all the construction materials – bricks, glass, computers – on that journey. We chose it because that community has had no access to computers at all in the past, so we could document the impact not just of the School In the Cloud, but of the arrival of the Internet.

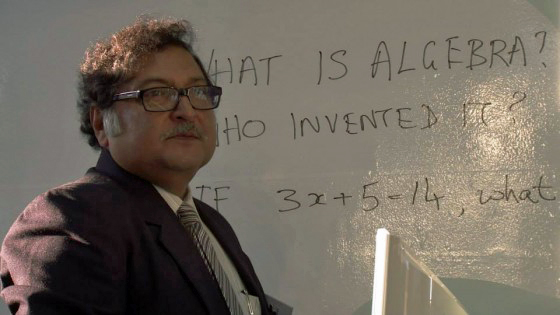

Sugata Mitra watches a group of children as they investigate the question: What is algebra? Photo: Courtesy of Jerry Rothwell

Talk to me a little bit about the kids.

I’ve worked in two kinds of environments on this project — in India and in the UK. In India, it’s all about getting the adults out of the room. Then the kids will start teaching each other things with a lot of excitement. One girl in Chandrakona said to us, “I’m hoping that this project will help me go from being just a village girl to a modern girl.”

In a primary school in Gateshead, on the other hand, the teacher — Amy Dickinson — has taken on Sugata’s ideas and is encouraging colleagues across the school to use the facility for self-organized learning during school lessons. The teacher will start with a broad, almost philosophical question, like “How do you measure a mountain?” or “Will robots replace humans?” The conversations and exchanges that happen between the kids as they research are really interesting. It challenges teachers a bit, to step back from their role as a classroom leader, where they usually give strong direction and maintain a high degree of order. It’s about empowering the children. In Gateshead, there is a committee of young people in the school running the space. They’ll even bring forward a complaint if they feel a teacher is misusing the room in order to teach a conventional lesson or using it more like an IT suite.

So there’s a big difference between the Indian and British contexts. The current western education system already has more inquiry-based learning. It is part of teachers’ everyday practice; whereas in my limited experience of the Indian system, it’s far more likely to be a teacher at the front, writing on the chalkboard as the kids chant it and learn it by rote. Sugata’s ideas are an important challenge to that system, urging us to link the amazing resource of the Internet with children’s innate desire to learn about the world, placing the tools for learning in their hands. That doesn’t mean you don’t need teachers, but it means they have a different role.

As an artist, how has this been different from the other projects you have worked on? Has it influenced the kinds of projects you will take on in the future?

This is my fifth feature documentary. Each of my films have been on very different topics. One was about a sailor who faked his journey around the world, another was about a sperm donor whose kids were coming to find him, and my most recent was about two young Ethiopian girls who want to be athletes. I guess the common theme is trying to tell stories from the bottom up, from within the character’s experience instead of commentating on it from the outside. I try to embed the film in the point of view of those it is about. For School in the Cloud, I’m working alongside Indian filmmaker Ranu Ghosh, who lives in Kolkata and has been able to develop close relationships with the families. One aspect of the project which is different from my previous films is that in some ways it’s a film about ideas — almost like a science or philosophy documentary — because of the nature of the person Sugata is. He is an incredibly inquisitive man, about everything. You want to capture that in the film, because he is so engaging.

Read more about the School in the Cloud »

Find out about the Sundance Institute | TED Prize Filmmaker Award »

This post originally ran on the TED Prize Blog. Read more about TED Prize wishes »

Comments (13)

Pingback: An Interesting Exchange With Sugata Mitra | Larry Ferlazzo’s Websites of the Day…