[ted id=1638 width=560 height=315]

The term “fiscal cliff” is controversial. So Adam Davidson, the New York Times Magazine columnist and co-host of NPR’s Planet Money, prefers to call it “the self-imposed, self-destructive arbitrary deadline about resolving an inevitable problem.”

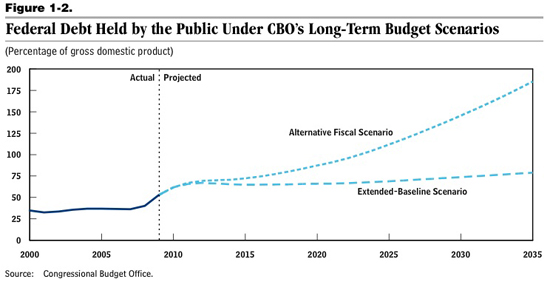

In today’s talk, filmed in TED’s New York office on Monday, Davidson explains what the fiscal cliff is and why it is so contentious. The easiest way to understand the fiscal cliff is to look at the graph below. In it, the Congressional Budget Office projects two future scenarios, the solid line showing what will happen if Bush-era tax cuts are allowed to expire in January and if government spending on everything other than major programs were cut significantly. The dotted line is what would happen if Congress opts to extend Bush-era tax cuts and does not curb government spending.

“Sometime in the next 20 years, if Congress does absolutely nothing, we’re going to hit a moment where the world’s investors and bond-buyers say, ‘We don’t trust America anymore. We’re not going to lend them any money except at really high interest rates.’ And at that moment, our economy collapses,” says Davidson. “We’re there in 20 years — we have lots of time to avoid that crisis. The fiscal cliff is one more attempt at getting the two sides to resolve the crisis.”

The crudest breakdown of the disagreement: Democrats see the way to solve the crisis as increasing taxes, especially on the rich. Meanwhile, Republicans see the key to ending the crisis as lowering government spending, to the point where taxes can be lowered too.

“When you think about the economy through these two different lenses, you understand why this crisis is so hard to solve,” says Davidson. “The worse the crisis gets, the higher the stakes, the more each side thinks they know the answer and that the other side is just going to ruin everything.”

There is hope, though, says Davidson. While Congress is embroiled in this battle, the American people are in general “moderate, pragmatic Centrists” when it comes to fiscal policy. By large, Davidson says Americans agree on the major government expenditures — Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid — though they see room for tweaks to make these systems more stable. (Defense spending, that’s another issue.) “We get to fight about all sorts of other issues — we get to hate each other on gun control, abortion, the environment — but on these fiscal issues, we are not as nearly divided as people say,” says Davidson.

In fact, when it comes to the American population at large, party identification isn’t as strong as it seems, says Davidson.

“We tend in this country to talk about Democrats and Republicans, and think there’s little group over there called Independents that’s maybe 2%,” says Davidson. “That is not the case and it has not been the case for most of modern American history.”

So, will Congress be able to diffuse the ideological butting-of-heads and solve this crisis, or will the United States drop off the edge of the fiscal cliff?

If history is any indicator, a compromise will emerge. As Davidson points out in his talk, deep-rooted battles about money have been a regular feature of American history. Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson battled about whether there should be a central bank. In 1913, there was a battle over the Federal Reserve. And then came disagreement about the gold standard, which was abandoned in 1933.

“Each of those times, we were on the verge of collapse, and nothing happened at all,” says Davidson. “Throughout it all, the dollar has been one of the most long-standing, stable, reasonable currencies — no matter how scared we’re supposed to be.”

To hear Davidson’s powerful metaphors for how both American political parties think about the economy, watch his talk. And below, some of our favorite Adam Davidson stories from Planet Money, “It’s the Economy” and more.

The ‘Mad Men’ Economic Miracle, The New York Times Magazine (Dec. 4, 2012)

Cliffhangers may have been around for more than a thousand years — since at least the composition of “One Thousand and One Nights” — but no one has monetized them as brilliantly as cable networks. In order to get paid, Charles Dickens had to sell the next chapter of his serialized novels; in order to sell advertising, ABC had to order more episodes of its hit show “Lost.” But for the next several months, AMC is converting our eagerness into millions of dollars without showing a single new episode.

Cable TV has developed one of the most clever business models in our modern economy.

The Giant Pool of Money, This American Life (May 8, 2008)

This American Life producer Alex Blumberg teams up with NPR’s Adam Davidson for the surprisingly entertaining story of how the U.S. got itself into a housing crisis. They talk to people who were actually working in the housing, banking, finance and mortgage industries, about what they thought during the boom times, and why the bust happened. And they explain that a lot of it has to do with the giant global pool of money.

Listen to this classic episode >>

This Man Makes Beautiful Suits, But He Can’t Afford To Buy One, Planet Money (Sept. 7 2012)

Peter Frew is one of a tiny number of people left in the United States who can — entirely on his own, using almost no machinery — make a classic bespoke suit. He can measure you, draw a pattern, cut the fabric and then hand-stitch a suit designed to fit your body perfectly.

Frew spent more than a decade as an apprentice for a remarkable tailor in his native Jamaica. He now sells his suits for about $4,000. Since New York is filled with very rich people who see their suits as an essential uniform, Frew has all the orders he can handle.

When I first heard about Frew and his remarkable skill, I thought: That guy must make a fortune. I was wrong.

Skills don’t pay the bills, The New York Times Magazine (Nov. 20, 2012)

Earlier this month, hoping to understand the future of the moribund manufacturing job market, I visited the engineering technology program at Queensborough Community College in New York City. I knew that advanced manufacturing had become reliant on computers, yet the classroom I visited had nothing but computers. As the instructor Joseph Goldenberg explained, today’s skilled factory worker is really a hybrid of an old-school machinist and a computer programmer. Goldenberg’s intro class starts with the basics of how to use cutting tools to shape a raw piece of metal. Then the real work begins: students learn to write the computer code that tells a machine how to do it much faster.

Nearly six million factory jobs, almost a third of the entire manufacturing industry, have disappeared since 2000.

What Do the Dow’s Daily Swings Mean? Not Much, Planet Money (Feb. 9, 2012)

Turn on the news on any given day, and you’re likely to hear about the Dow Jones industrial average. It is the most frequently checked, and cited, proxy of U.S. economic health. But a lot of people — maybe most — don’t even know what it is. It’s just the stock prices of 30 big companies, summed up and roughly averaged. That’s it.

And what does the daily movement of this number have to do with the lives of most Americans? Not much.

The Haiti Aid Dilemma, Frontline (June 2010)

Read more on this story >>

My Big Fat Belizean, Singaporean Bank Account, The New York Times Magazine (July 24, 2012)

Earlier this month, I decided to see how hard it would be to set up my own offshore bank account. I figured it would be pretty difficult, because I’m not rich and don’t have a team of tax lawyers to oversee my money and because the E.U. and U.S. governments have been cracking down on tax havens by imposing stricter tax-sharing requirements. So I proceeded with some caution.

Looking for a High-Tech Job? Try Cotton, Planet Money (May 27, 2011)

Unemployment is still at 9 percent, leaving more than 12 million Americans without work. But there are bright spots in the U.S. economy. Planet Money and Wired Magazine have spent the last six months scouring economic data and interviewing people around the country to find out what areas of our economy are doing well. It’s part of a series called Smart Jobs.

Let me boil our findings down to one quick tip. If you want a job — a good job, a job that will be around for a while and pays well — find a company that creates some new product or service that nobody else has.

For example: a greenhouse in Memphis, Tennessee.

Comments