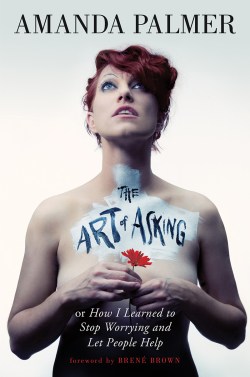

Amanda Palmer’s new book grew out of a simple fact: that she couldn’t cram every relevant story into her 14-minute TED Talk. So she has expanded her talk, “The art of asking,” which focuses on how artists can (and should) ask those who love their work for help, into the book The Art of Asking: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Let People Help, about the need to ask for help more generally. And in another interesting twist for TED fans, the foreword to the book was written by one Brené Brown, who gave the fourth most-watched talk of all time, “The power of vulnerability.”

We asked Palmer a few questions about the process of turning her talk into a book and about the experience of working with Brown. Below, an edited transcript.

Would you rather have give your TED Talk 10 times in a row to an audience of clowns, or have to write one more chapter of your book with a deadline of tomorrow morning?

Oh my god. Great. Well, I love clowns. So as long as I didn’t have to actually memorize that sucker word for word and could just kind of summarize it. Or maybe I could mime the TED talk for the clowns? Maybe this could become a multi-media interactive performance in which the clowns responded to my TED mime-talk? Maybe all the clowns could be wearing Google Glass and we could webcast this?

Wait, forget it. I’ll just write another chapter of the book. Easier.

What was the biggest challenge of bringing your idea from a talk to the written page?

Funny enough, it was a challenge to try to capture the beautiful economy of the talk in 300 pages. That 14-minute time limit was the greatest gift: I’m very glad my talk wasn’t longer, because I don’t think it would have been quite so effective, emotionally, and I don’t think it would have gone viral.

When I was working on the talk with Jamy Ian Swiss, a friend who became my default coach, he kept saying, “Cut that part, Amanda, you can put it in the book. Cut this too — save it for the book.” At the time, there was no book. We just had the assumption that maybe someday, there’d be an outlet for these other stories. The pieces I cut would probably be surprising to some. They might seem off-topic. But to me, these are essential riffs on the same theme as my talk: my job as a stripper, my marriage difficulties around the topic of money and help, my experiences with abortion and having to deal with certain kinds of pain in isolation, my best friend’s cancer battle leading to a cancelled tour. All of these things had a lot to do with “the art of asking,” but they weren’t going to fit neatly into a 14-minute talk.

When I was working on the talk with Jamy Ian Swiss, a friend who became my default coach, he kept saying, “Cut that part, Amanda, you can put it in the book. Cut this too — save it for the book.” At the time, there was no book. We just had the assumption that maybe someday, there’d be an outlet for these other stories. The pieces I cut would probably be surprising to some. They might seem off-topic. But to me, these are essential riffs on the same theme as my talk: my job as a stripper, my marriage difficulties around the topic of money and help, my experiences with abortion and having to deal with certain kinds of pain in isolation, my best friend’s cancer battle leading to a cancelled tour. All of these things had a lot to do with “the art of asking,” but they weren’t going to fit neatly into a 14-minute talk.

So I cut a lot of stories from the TED talk, and they’d been lying there fallow on the cutting room floor, waiting to be threaded in. The book happened much faster than I thought, but I’m also glad it happened fast, before all those tethered balls in the air had a chance to land and disconnect. And when I got my book advance, I hired Jamy for an actual salary this time to be my book doula. It all worked out pretty beautifully.

What types of help did you find are the hardest for you to ask for? How do you push through that?

I’ve found that everybody has an Achilles’ heel when it comes to asking. I know a lot of people who can boldly ask for a raise, but they can’t ask for a hug. And I know a lot of people with the opposite problem. My personal kryptonite, and I detail it painfully in the book, is taking financial help from my husband. I’m happy taking millions of dollars from strangers, but it’s taken me a long time to get used to taking help from him. My life finally hit a point where I saw the bigger picture — it took my friend getting fatally ill, but this is all part of the journey. I noticed that I ask too much of myself. Letting myself off the hook is one of my biggest projects.

Speaking of your husband, he is quite a well-known writer. Did you let him edit your manuscript or were you hesitant to ask for help on that?

I wasn’t at all hesitant: I utilized the hell out of Neil Gaiman with this book. But the first ask wasn’t about editing or shaping or writing: it was about letting go of his wife for two months so I could write in solitude. That was difficult to do. And the minute I finished my first, hulking 150,000 word manuscript, I handed it over to him, squeezed my eyes shut and said, “Cut out 50,000 words.” And he sat down for two days, and cut away the fat. That was a massive act of trust. I trusted his writer’s eye so greatly that I didn’t even read his cut manuscript. We started with Neil’s edit as a fresh draft. And in the final days of last-minute editing, Neil suggested a fantastic order-switch with the pieces of the book that wound up unlocking a problem. The guy can write, but he’s also a fantastic editor. I owe him one.

And Brené Brown also helped by writing the foreword of the book. How did you two meet?

I found Brené’s talk when I was on a TED-watching marathon while writing my own talk back in 2013. For about the week before cracking down to write my first draft, I immersed myself on TED.com and watched about 50 talks — focusing on the most-viewed — to see how people were getting their ideas across most effectively. I found a few heroes during that week, some of whom have come into my life since as real heroes, like Amy Cuddy and Jill Bolte Taylor, both of whom I got to meet and hug in the flesh at TED itself and both of whom I now treasure as friends. But Brené’s talk especially moved me. A few weeks before leaving for Australia, where I wrote the book, I was in the Trident Bookstore in Boston, and saw Daring Greatly lying on the staff picks table. I picked it up and started reading it. I was floored: she’d basically written the same book that I had in mind. Hers was academic and anecdotal and mine was pure memoir, but still the threads were exactly the same. She even used a Velveteen Rabbit story, which I couldn’t believe — I’d been planning on quoting the exact same passage. So I sent Brené a DM on Twitter, asking her to write the intro. I was so honored when she said yes, and I think what she wrote is absolutely perfect.

What did she write in her foreword that most surprised you?

I loved, most of all, that Brené was reaching out to the rest of the world in a way that I couldn’t. She works at a university, lives a domestic life, goes to church; but she sees her life reflected directly in my weird rock-and-roll couchsurfing existence. This is what made Brené’s book so great, in itself: our situations are different, but our emotional experiences give us all a common ground. We all feel shame, vulnerability, fear. I’m so incredibly proud to be a small voice in what feels like a zeitgeist of women writers lately, including Amy Cuddy — who’s about to bust out with her own book — and Laurie Penny and Caitlin Moran, who are embracing these commonalities we humans have and casting our own stories into the net of understanding. I think it’s a beautiful time to be alive: it’s like we’re all doing our little bit to shine our teeny personal flashlights into the wide, big, dark. With enough of us, the dark is receding and things are taking shape. I can’t wait to see what we find there.

Comments (5)