TIME Editor-at-Large Bobby Ghosh covers global affairs and the Middle East. For five years he served as the magazine’s Baghdad bureau chief and, by the end of his tenure, was the longest serving print journalist in Iraq. Most recently Ghosh wrote a cover story on Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi, arguably the most important man in the Middle East at this moment.

In his informative TED Talk on why global jihad is losing, Ghosh discusses how Osama bin Laden misappropriated the word “jihad” — not just for the West but also for Arabs in the Middle East. While he painted it as a violent global holy war, in Islam the term has long referred to the internal, personal struggle to be a better person. Ghosh asserts that with the end of bin Laden came the end of this brand of bin Ladenism. And along with it, the concept of the global jihad.

Ghosh’s ideas are fascinating, but also raise a lot of questions. I caught up with him recently by email to hear more.

Do the Western media and/or government have a vested interest in perpetuating fear mongering in the form of jihadi rhetoric? What does the Western media get wrong about bin Ladenism and jihad?

No, I don’t believe Western media or governments have an interest in perpetuating fear about jihad. They misunderstand the word, but that’s not deliberate. They come by their misunderstanding honestly! The problem, as I say in my talk, is that extremists in the Muslim world have appropriated the word and twisted its meaning — so much so that many Muslims are now unsure what jihad stands for. So it would be unfair to blame Westerners for having the same uncertainty. There are some individuals in the West, just as there are in the East, who play up the worst interpretations, but they are a micro-minority.

How close do you think bin Ladenism is to being over? To what extent is jihad totally local?

I feel that the cult of bin Laden is on its last legs. Much of what passes for violent “jihad” today — whether it’s in Afghanistan, or Mali, or Somalia or Iraq — is, when you look closely, a contest for power and resources in those countries. The people behind the violence sometimes use the rhetoric of global jihad, and claim to be following in bin Laden’s footsteps, but in reality their interests are much narrower than his.

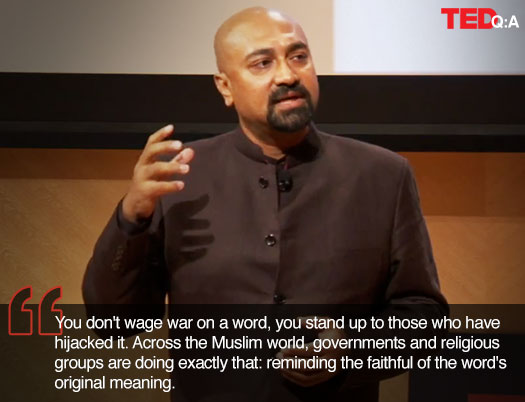

You say at the end of your talk that the original meaning of “jihad” can be reclaimed by Muslims who want peace. Can you elaborate on how this can be done? What does that mean on the ground-level? How do you wage a war on a word?

You don’t wage war on a word, you stand up to those who have hijacked it. Across the Muslim world, governments, civil-society organizations and religious groups are doing exactly that. Governments use policing and counterterror strategies to target extremist groups, but the challenge for civil-society and religious groups is to remind the faithful of the word’s original meaning. This is being done through education, through activism and through preaching in mosques and on TV. It’s an uphill struggle: corrupting a concept is easier than redeeming it.

One thing to note: extremists are actually helping to undermine their argument. By killing innocents (many of them Muslims), they are exposing the hollowness of their claims to be protecting the faith. Muslims can see through this.

It helps, too, that in the Arab world there is now demonstrable proof that change can happen without resorting to suicide bombs and IEDs. The Arab Spring may look messy to us in the West, but young people in that region are galvanized by the possibility of changing their lot. They’ve seen that dictators can be toppled by street protest. Bin Laden could never have imagined that.

It’s commonly believed that in the Koran there’s more than one original meaning of jihad, not just the internal struggle you speak of in your talk, but also the physical struggle to defend Islam. How would you respond to those who wish to perpetuate this meaning?

Yes, depending on how you choose to interpret it, jihad has more than one meaning, but nowhere in the Koran does it say it’s okay to kill innocent people. On the contrary, there are many passages that explicitly prohibit such killing.

In your article “The Agents of Outrage,” you mention Internet war-mongering by people like Sam Bacile, Terry Jones and Sheik Khaled Abdallah. What makes this specific kind of drudgery attractive to web users? Could this kind of outrage-machinery mobilization have been possible before the Internet?

The Internet makes it easier for these people to spread their poison, but equally, it allows the antidote to spread quickly. For every website that espouses hateful interpretations of the Koran, there are a dozen that seek to explain Islam in a reasoned manner. The trouble is not with the web, it’s with what happens in the “real” world, where agents provocateur sow discord, militants thrive in it, politicians stoke up the fear, and some people get carried away by it all.

I can’t understand the motivation of people who spread hate and fear in the name of faith, whatever their faith.

Finally: Yahoo! I’m glad you’re alive.

Thanks. … I think!

[ted id=1623 width=560 height=315]

Comments (1)

Pingback: An uphill battle to reclaim “jihad”: A Q&A with Bobby Ghosh | Free Thinking