Economist George Ayittey gave a blistering talk at TEDGlobal 2007, laying out his case that not only has Western aid not helped in most African countries — it’s actually hurting.

Economist George Ayittey gave a blistering talk at TEDGlobal 2007, laying out his case that not only has Western aid not helped in most African countries — it’s actually hurting.

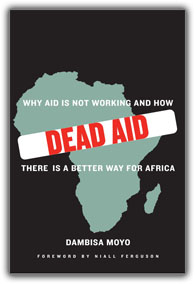

We asked Ayittey for his thoughts on the new book Dead Aid, which has lately been burning up the talk shows and opinion columns with a message similar to Ayittey’s. Author Dambisa Moyo says that aid is killing the very countries it’s supposed to help. She singles out for criticism the celebrity crusades to “save Africa,” and the skewing view they present of African life.

(You can also download the unedited notes for this interview, including reading list, sources and more.)

Dambisa Moyo’s new book is drawing new attention to the question of aid in Africa, and her thesis is quite like yours, but aimed at a mass-market audience (as she said on Charlie Rose). Do you think it is risky to sensationalize the issue?

I don’t think Dambisa is sensationalizing the issue strong enough. Americans were justifiably outraged when AIG, which received billions in U.S. taxpayer money in bailouts, paid out hefty bonuses to its executives. So where is the outrage when African leaders, who receive U.S. taxpayers’ money in foreign aid, build palaces for themselves while their people wallow in abject poverty?

More important, the presumption that Africans don’t know what is good for them and that Americans or other foreigners know what is best for Africans is extremely offensive. If you want to help American farmers, you ask them what sort of help they need and whether such assistance is working. Why don’t Americans ask Africans what type of aid they need and whether the aid Americans have provided is working? So what is wrong with an African, Dambisa, telling Americans that the foreign aid they are providing isn’t working and it is “Dead Aid”?

It’s clear that Moyo’s thesis draws from your work. How would you respond to those who assert that her views and yours are idealistic and ideological?

Our critics have not been paying attention to the literature on foreign aid. Our views are neither idealistic nor ideological but rather factual. There are three types of foreign aid: humanitarian relief aid, given to victims of natural disasters such as earthquakes, cyclones and floods; military aid; and economic development assistance. We have no qualms with humanitarian aid, and I am sure our critics would agree that military aid to tyrannical regimes in Africa is the least desirable. Much confusion, however, surrounds the third, also known as official development assistance or ODA. Contrary to popular misconceptions, ODA is not “free.” It is essentially a “soft loan,” or loan granted on extremely generous or “concessionary” terms.

The consensus that emerged decades ago was that foreign aid had not been effective in reversing Africa’s economic decline. Dambisa and I are simply restating a fact. And it is not just Africa. That foreign aid has failed to accelerate economic development in the Third World generally was also accepted. In 1999, the United Nations declared that 70 countries — aid recipients all — are now poorer than they were in 1980. An incredible 43 were worse off than in 1970. “Chaos, slaughter, poverty and ruin stalked Third World states, irrespective of how much foreign assistance they received,” wrote the Washington Post, on Nov. 25, 1999. Except for Haiti, all of the 13 foreign aid failures cited — Somalia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Angola, Chad, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Zaire, Mozambique, Ethiopia and Sudan — were in Sub-Saharan Africa. The African countries that received the most aid — Somalia, Liberia and Zaire — slid into virtual anarchy.

Is there a fundamental place where you diverge from Moyo?

Though we are both on point regarding the failure of aid programs in Africa, we diverge in two respects.

First, Dambisa wants all aid to Africa stopped in five years, which won’t happen. Over the decades, various African civic groups and persons, including myself, have called for a cutoff of aid to Africa. In a report drafted during a five-day forum hosted by UNESCO in Paris in 1995, more than 500 African political and civic leaders urged donor nations to cut off funds to African dictatorships and called for free elections in such nations within two years. If the West could impose sanctions against Libya and South Africa, then Africans could also call for sanctions against their own illegal regimes.

Second, I believe that the foreign aid resources Africa desperately needs to launch into self-sustaining growth and prosperity can be found in Africa itself, not in China as Dambisa believes.

Moyo’s work speaks to that deep urge among Westerners to “do something” — even something that may be deeply unproductive. What’s a more productive way to “do something”?

I think Westerners should resist that urge to “do something,” because the worst type of help one can receive is that which doesn’t solve your problem but compounds it. If Westerners want to help, they must carefully scrutinize and reform current aid policies to make them more effective. Both the Clinton and Bush administrations tried to but failed. Business as usual is no longer an option, which is what both Dambisa and I are against.

Foreign aid should be tied not on promises of African leaders but to the establishment of a few critical institutions:

+ An independent central bank: to assure monetary and economic stability, as well as stanch capital flight out of Africa. If possible, governors of central banks in a region, say West Africa, may be rotated to achieve such independence. The importance of this institution resides in the fact that the ruling bandits not only plunder the central bank but also use its facilities to transfer the loot abroad.

+ An independent judiciary — essential for the rule of law. Supreme Court judges may also be rotated within a region.

+ A free and independent media to ensure free flow of information. The first step is solving a social problem is to expose it, which is the business of news practitioners. The state-controlled or state-owned media would not expose corruption, repression, human rights violations and other crimes against humanity. In fact, it is far easier to plunder and repress people when they are kept in the dark. The media needs to be taken out of the hands of government.

+ An independent Electoral Commission to avoid situations where African despots write electoral rules, appoint a fawning coterie of sycophants as electoral commissioners, throw opposition leaders in jail and hold coconut elections to return themselves to power.

+ An efficient and professional civil service, which will deliver essential social services to the people on the basis of need and not on the basis of ethnicity or political affiliation.

+ The establishment of a neutral and professional armed and security forces.

The establishment of these institutions would empower Africans to instigate change from within. For example, the two great antidotes against corruption are an independent media and an independent judiciary. But only 8 African countries have a free media in 2003, according Freedom House. These institutions cannot be established by the leaders or the ruling elites (conflict of interest); they must be established by civil society. Each professional body has a “code of ethics,” which should be re-written by the members themselves to eschew politics and uphold professionalism. Start with the “military code,” and then the “bar code,” the “civil service code” and so on. These reforms, in turn, will help establish in Africa an environment conductive to investment and economic activity. But the leadership is not interested. Period.

Effective foreign aid programs are those that are “institution-based.” Give Africa the above 6 critical institutions and the people will do the rest of the job.

Africa is poor because it is not free.

George Ayittey responded to emailed questions from TEDAfrica Director Emeka Okafor and TED.com editor Emily McManus. Download the unedited notes from this interview, an 11-page PDF with reading lists, noted sources, and much more. TED intern Mischa Nachtigal prepared this edited blog post.

Comments (24)

Pingback: Week Seven — Dambisa Moyo and Foreign Aid | inter/multicultural case studies

Pingback: Week 7: Moyo | Case Studies in a Multicultural World

Pingback: Dambisa Moyo and Aid to Africa [Week 7] | inter/multicultural case studies

Pingback: Moyo and Why Aid is Not Working | Digital Global Studies

Pingback: MSc Humanitarian Logistics and Emergency Management | Business Matters

Pingback: Hulp aan overheid funest voor ontwikkelingsland

Pingback: Whither Foreign Aid? « Globo Diplo

Pingback: La inútil ayuda a África « Juan Pablo Arenas

Pingback: Viser au coeur (JA) « In4ex's Blog