[ted id=1537]

Two years ago, Lebanese-Egyptian artist and historian Bahia Shehab was invited to join an exhibit commemorating 100 years of Islamic art in Europe. The catch: she had to use Arabic script in her work.

“As an artist, a woman, an Arab and a human being living in the year 2010, I only had one thing to say—I wanted to say no,” Shehab says in this powerful talk from TEDGlobal 2012. “In Arabic, we say ‘No and a thousand times no.’”

Shehab decided to focus on the Arabic script for “no.” She collected a thousand different visual representations of the word “no” printed, stitched, molded, engraved and cast over the past 1,400 years on vases, tombstones and walls, in locations as far-flung as Spain and the border of China. She called the installation A Thousand Times No.

A year later, a revolution began in Egypt. “Life stopped for 18 days,” says Shehab. “On the 12th of February, we naively celebrated on the streets of Cairo believing that the revolution had succeeded.”

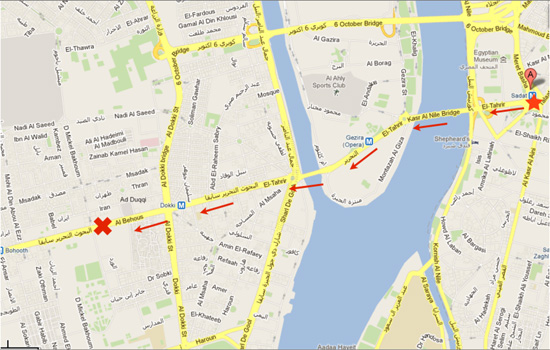

Months later, as the reaction to the revolution turned violent and the country braced itself for a much longer battle, Shehab began to see a connection between A Thousand Times No and her country’s situation. She took to the streets, spray-painting “no” on walls throughout Cairo.

“I did not feel that I could live in a city where people were being killed and thrown like garbage on the street,” Shehab said, describing her first image, which read “no to military rule” in a script taken from a tombstone. “A series of ‘no’s came out of the book like ammunition.”

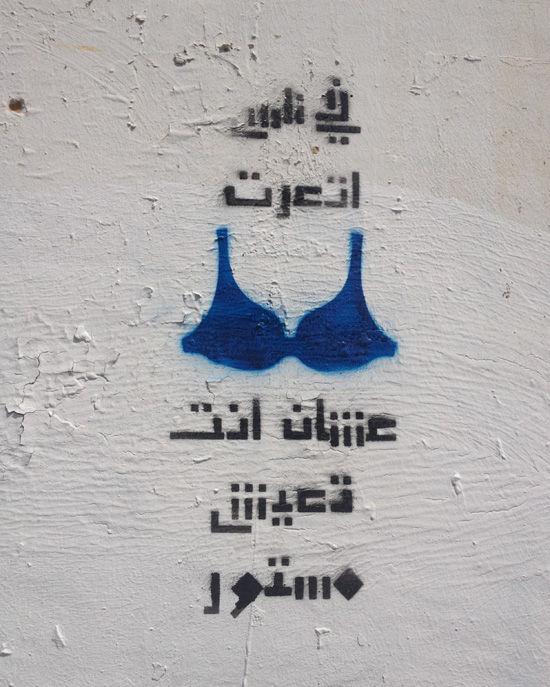

Some of the “no”s that followed: No to a new pharaoh. No to violence. No to killing men of religion. No to burning books. No to the stripping of veiled women.

To hear more about Shehab’s art, and the specific meaning of these “no”s, watch her beautiful talk and read the TED Blog’s Q&A with her. Below, read about two new projects Shehab has been creating in Cairo.

Shehab tells the TED Blog:

This is a campaign that I sprayed before the presidential elections, in May and June of 2012. The mass sentiment was very low and there were a lot of anti-revolution feelings in the air, even by people who were strong supporters of the revolution. I did this campaign to remind people of the aims of the revolutions and the sacrifices that people made for us to get to where we are. It is called “There are people” and the five stencils read:

There are people who have had their head put to the ground so that you can raise your head up high.

There are people who have been stripped naked so you can live decently.

There are people who have lost their eyes so you can see.

There are people who have been imprisoned so you can live freely.

There are people who have died so you can live.

The authorities erased this campaign three days after I sprayed it, which proved to me one thing—the faster they erase, the stronger the message. So I sprayed it again a month later, this time with bigger images and clearer text.

Two weeks after that, somebody took a photo of it and the campaign went viral. Three weeks later, it was featured on the third page of one of the leading local newspapers, right under the image of Mubarak. The message has surpassed the medium and I was very proud.

This is a campaign I did on speed bumps in August of 2012. I took a street that leads out of Tahrir Square, and I painted a message before the speed bump: “Beware of Speed Bumps.” After the bump, I painted: “Long live the revolution.”

To the taxi drivers — who were thanking me for highlighting the problem at 4 in the morning of a Ramadan day — I was doing a socially responsible act. I was doing the work the government should do to keep them from harm by highlighting a speed bump on a busy street. But to someone with more insight, they will understand that I am highlighting the fact that for us as people leaving Tahrir Square and heading towards a new phase of the revolution, we should be aware of speed bumps and we should keep the main aims of the revolution very clear in our minds.

Comments (10)

Pingback: 12 Innovative Women in the Middle East | StepFeed

Pingback: In the Skype Studio: How social media transforms ideas and movements - The Online List

Pingback: revolution in Egypt and why I wanted to feminize it: An essay | PLUS

Pingback: The new revolution in Egypt and why I wanted to feminize it: An essay | Best Science News

Pingback: The new revolution in Egypt and why I wanted to feminize it: An essay | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: An ode to 51 lost children: Fellows Friday with Bahia Shehab | Krantenkoppen Tech

Pingback: [A Thousand Times No] : DAYDREAMS