Bora Yoon builds soundscapes out of instruments and found objects from assorted centuries and cultures, weaving an unlikely and undulating web of immersive sound. As a live performer, the Korean-American composer, vocalist and sound architect often seeks interesting spaces in which to work, creating music specifically for each site. Now she’s created Sunken Cathedral, a multimedia album that lets listeners take the experience of sound and space with them. Here, Yoon tells the TED Blog about the ideas behind this dynamic work, which will culminate in a live performance in January 2015.

You’ve launched an IndieGoGo campaign for Sunken Cathedral, but the record is done, right?

Yes. It’s an enormous beast of a multi-tentacled project that I have been working on for seven years, and it’s all unveiling now in a four-part, year-long rollout—a transformation from record to the theatrical stage. The Sunken Cathedral album—which Innova Recordings released online and on CD in late April—is essentially a musical blueprint upon which everything else will be built.

A trilogy of interactive music videos will be released this month for the iPad with the Gralbum Collective—it’s short for graphic album (think: visual album)—featuring the dangerously beautiful kinetic sculptures of U-Ram Choe, who is a crazy, wonderful Seoul-based artist. That will give the piece a virtual and cinematic structure to engage with. A series of music videos will follow in the summer by filmmaker Brock Labrenz, Toni Dove, with remixes by King Britt and DJ Scientific. But the whole thing will culminate as a staged multimedia theater production — essentially the experience of the cathedral itself. That will premiere at the PROTOTYPE Festival, co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and HERE Art Center, in January 2015. So the Indiegogo campaign will help pay for this transformation from record into a staged world premiere.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kfpurmaJw-s&w=982&h=552]

Above: Watch Bora Yoon perform “Sons Nouveaux” live at TED2014.

You typically do site-specific, live musical performances. What possessed you to make such a massive, multifaceted work?

I wanted to create a project that built itself—like musical architecture—from the invisible to the tangible and visceral. Living in New York City, I was doing one-off events and projects, but as someone whose work is already really hard to define, it felt discouraging to be building what seemed a super-disparate and random body of work. So when I got a recording grant in 2009 from the Sorel Organization for Women Composers, I decided to take the opportunity to chip away at a larger aesthetic. I wanted to show a concept of who I am and help define what my artistic practice actually is about — sound and space, environment, experience.

While working on it, I started to understand that because I work site-specifically — or architecturally — the project would have to be multidimensional and multimedia, so that people can engage with it in different ways. And because we live in such an increasingly visual age, I think you have to make things an experience. You can’t just put out a record. When I make music, I definitely see music. I know what environment I’m making, what memory I’m painting, or environment or landscape I’m evoking. These videos are a way for me to show that. It’s visual poetry to support the sonic language that’s happening.

You’re a classically trained musician, right?

Yes. I had a very stereotypical Asian-American upbringing outside of Chicago — with piano, Suzuki violin. I started singing in junior high, and that was really my first love. Choral music was where I started to notice how vertical and horizontal music can happen at the same time. Even though you’re singing one part within many, you’re aware of the vertical staff: you make harmony and chords that are going by in the horizontal aspect of time, and the arc of phrases. When you put vertical and horizontal together, the feeling of transport happens. I always feel art is successful when you can take people somewhere. That’s the litmus test for me. Have you transported people somewhere, and returned them transformed? It’s a ride.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Qt2GdGPj0s&w=982&h=552]

Above: Watch “Father Time” from Sunken Cathedral, directed by filmmaker Adam Larsen, and featuring the kinetic sculpture of Seoul-based artist U-Ram Choe. It’s the first of three interactive music videos releasing on new iPad app Gralbum this May.

I majored in music and creative writing at Ithaca College, living between a conservatory setting and a town that was liberal enough to foster this singer-songwriter poetry scene, as well as having underground electronic parties. That weird, disparate identity in college shaped who I am now. The poet singer-songwriter in me definitely wants to find different ways to use words—like how Laurie Anderson uses text, or how Björk can turn a couplet around four times and have it mean something different every time. Then there’s the music conservatory nerd. I have perfect pitch, so everything, to me, has a pitch. The car honk, the fork against glass, that’s a D. Or the radiator in A flat. When I’m microwaving something, I harmonize with that. The beautiful thing about sound is that when you elongate anything, there is tonal information. That’s really the gateway between sound and music. Once you’ve got it, you can harmonize with any sound’s tonal center, or make different chords around it.

That’s really how a lot of my object work started. I’d be cooking in the kitchen, or putting out the recycling, and be like, “Oh, that’s a really cool sound!” I’d keep things because of their interesting sounds, texture, oddity. I became enamored of associations, or triggers. Why does this sound take me back to my childhood? This sound is a dream space, or a distant memory. And the sound makers are visual objects themselves. The gestural language starts to build on working with these.

In performance, I’m pretty adamant about the fact that the audience should see how all the sounds are made. It does mean that I carry around the kitchen sink, but I think it’s important that we have that tactile and visual connection. And I’m a pack rat. The cellphone I use—it’s amazing what that old-school Samsung 2G cellphone has done for my life and career. It was a phone with a broken screen—I’d dropped it—but it had a really nice melodic tone to it that reminded me of my Casio in the ’80s. So when I put that through a loop pedal, soundscapes developed.

Performing site-specific music created for the Ann Hamilton Tower, Oliver Ranch, with Sympho. Geyserville, California. Directed by Paul Haas. Photo: Christopher Bono

How did your work with space begin?

As a choral singer, I’ve always gravitated towards interesting acoustical structures, for their resonance and their history. When you work in the recording studio, you are given a great artistic freedom to curate how to re-create the sense of space/place by layering tracks, playing with the proximity of the mic and creating jarring combinations of near/far, tactile/ambient. You’re creating sonic surrealism for the ear and mind. I think of music as a spatial environment. Essentially, colored wind. A type of weather that fills the room. I work with different textures and hues at different times of day or night. I work with unusual architecture and interesting historical spaces, because they offer a unique acoustic, and a context of memory to tap into. When I walk into a space, I try to activate its history, evoke its memory, think, “What does this room want to say? What instruments can I use from different eras to give this room voice?” Superimposing music’s invisibility on architecture’s visibility can create a compound sense of time and place for the listener.

What you do on stage has its own internal logic, yet, with all the props and sounds, it also seems completely random. Is what you’re doing improvised or composed?

Composition is really just captured improvisation. But I do like to leave a little bit of margin in live performance—about 20%—for things to happen or to be reactive to the energy in the room. The room might be wanting a slower tempo than you’d planned. Each version has to fit the moment. A friend told me an awesome quote I carry with me: “It don’t matter what song you sing, as long as you sing the song that’s in the room.” I always take that to heart before I go on stage. I try to create an atmosphere that is resonant with people. I think the preposition is very important. Are you performing at people? Are you performing to people? Performing with people? For people? Alongside people? That’s the difference between whether it’s something they’ll really remember.

Do you have a notation system?

I do. They’re like little pictographs for me. It’s like an index card that shows me how I build the layers: viola loop, then vox, then megaphone, then cellphone, then glockenspiel. I know the order they come in. You start with a tone or rhythm, and then you build the other structures around it. Then you build it out; then you start putting drapes on it and you start putting birds in the sky. It really is like sonic drawing.

Record player, bowl, egg. A still from the workshop performance of Sunken Cathedral. Directed by Glynis Rigsby. Photo: Ash Hsie

Do you actively seek objects to make sound with? Or do you think, “I want a sound that’s going to express a certain kind of emotion,” and start looking for things to create that?

It works both ways. A lot of times I’ll come across a sound-making object and be fascinated by it. But sometimes it does work the opposite way. Either way, I know it’s important if it feels like a thread that you have to pull. You don’t really know what you’re pulling, or why your gut knows to, but the more you pull it, the more crazy stuff emerges. Your subconscious figures out some really weird and deep things along the way, too. Eventually your mind can zoom out and see what’s been building. For example, I realized a song that took a year-and-a-half to make was actually an enormous eulogy for my dad. This song, “In Paradisum,” is a medieval chant that is used ceremoniously, when the body is taken out of the church. It’s the transition chant between one life and the next. I’d woven that chant in with a storm of sounds I’d gathered from elsewhere. Then much later realized, “Wow, this is me actually dealing with my father’s death, 22 years later.” It was a way of “letting” that moment transmute. I had never talked about it my whole life. It’s weird how your creative mind and your subconscious self are always working, at very different paces and tempos. Sometimes you don’t even know what’s working in the background. That’s what’s remarkable about the creative process, and also what’s scary as hell about it.

The blood-red vinyl disc from the limited-edition collector’s double LP. Designed by Popular Noise. Photo: INNOVA Recordings

Sunken Cathedral also takes shape as a vinyl double album. Tell us a bit about that.

The LPs were designed and made as limited-edition fine-art pieces. The first record is a blood-red disc with an Ouroboros image of a snake biting its tail. When it spins, it continually swallows its tail. The black disc features stars, so when it spins it looks like a small spinning universe. The LP is very much symbolic of its tangible form. When you drop the needle on the blood-red record, the metaphor is that you’re amplifying what your blood might be saying. And the black record with the celestial stars holds the idea that we are recombinant matter. Old phonograph players used to be diamond-tipped, or sapphire-tipped in order to play records. I found out that when you die, you cannot just be cremated, your ashes can actually be compressed at such a high heat and pressure, you can be turned into a diamond. The LP edition has been designed to illuminate the mortal versus the timeless and universal planes—the recombinant matter and energy that we embody and continually circulate. The entire record plays with metaphors of cycles and circles, the rings on a tree or record. How you live through your life’s journey by way of valences.

I’m very excited about the last track on the record, “Doppler Dreams,” which I made in 2006 for a site-specific dance piece in the McCarren Park Pool, a 55,000-square-foot abandoned pool in Brooklyn. I composed a kinetic choral piece for seven sopranos on bicycles that rode around in different proximities, singing. The audience sat at the perimeter. Wherever you were sitting, you’d have a totally different sound composition than someone across the way, due to your own spatial organization. As the record spins to a close, it swoops in the same gesture: a small ring, and ring, and ring. That, to me, means I can die happy.

Music from AGORA II by Bora Yoon : feat. McCarren Pool, Brooklyn from Swirl Productions on Vimeo.

Above: Watch “Doppler Dreams”, a live site-specific kinetic choral work for 7 sopranos on bicycles in the 55,000-square-foot McCarren Pool.

Would you prefer people get the record rather than the CD and listen to it from beginning to end? Or should people dip in and out on various media?

Every iteration is medium-specific. The CD order is completely different than the LP order. The CD is made with the idea that people are going to listen to it on the train and in their office. It’s more palatable, not as heavy. Meanwhile, with the LP, just being present with a record governs a different listening experience. I thought about the fact that people would have to turn it over, and their expectations. What will be the first sound you hear when you drop the needle? You might hear wind. Or you might hear record crackles themselves.

On the first side, the first sound is actually a microcassette recording of my father in 1991. It is the only audio I have of him. I remember always knowing that I had that tape recorder somewhere. I tracked it down, and we put it right in at the top. This beat happens, these dogs bark, and then there’s the sound of a pencil scrawling on Bible pages. And then there’s the sample of my father saying, “Hey, do you have a piece of paper?” And my 10-year-old self saying, “Hmm?” “A piece of paper, I need to write something down.” And then you can hear the pencil. It’s like he framed it up himself — all these sounds now make sense, because of that sample.

This is what I mean when I say that sometimes the songs form themselves. I feel like I am just a person that weaves them together. My theater director Glynis Rigsby articulated it for me: “Bora, what you’re doing is like in film. You call it a compound image. If you have a shot that has a radio, an orange, and a glass of water, you’ll start to make connections. You start to come up with a story, you start making associations around what these things are. You do that with sound, and gesture.” The space between sounds is where the interesting tension, or the story, really is.

"g i f t" : ARCO : Tune-In Festival : Park Avenue Armory, NYC [HD] from Swirl Productions on Vimeo.

Above, watch “g i f t”, a site-specific symphonic commission with Sympho for the military drill hall at the Park Avenue Armory, NYC. Directed by Paul Haas

In your TED2014 Fellows talk, you talked about linking music as architecture with a sense of inner space.

This record gathers a lot of the site-specific pieces that I’ve made—whether in the McCarren Park Pool, in the Armory, or at the Ann Hamilton Tower. These were all different spaces. But its beauty lies in the telescoping of that architectural lens inward into the body as well. Architecture is often an amplification of the spaces we carry within us.

Cathedral architecture was really how the album was inspired, because cathedrals are modeled after the body. The arches are the ribcage, and the swells of the organ are its lungs. I started to connect this idea with ancient Chinese medicine, which correlates the various chambers of your body with holding different emotions. I wanted to ask, “How can we use that lens to telescope inward to explore elemental architecture within us? Our blood identity and cultural identity? What are the layers that make up who we are physically, psychologically, and how can I use that as a rubric to illuminate different musical spaces, or emotional spaces — even our relationship to how we navigate actual and external spaces?”

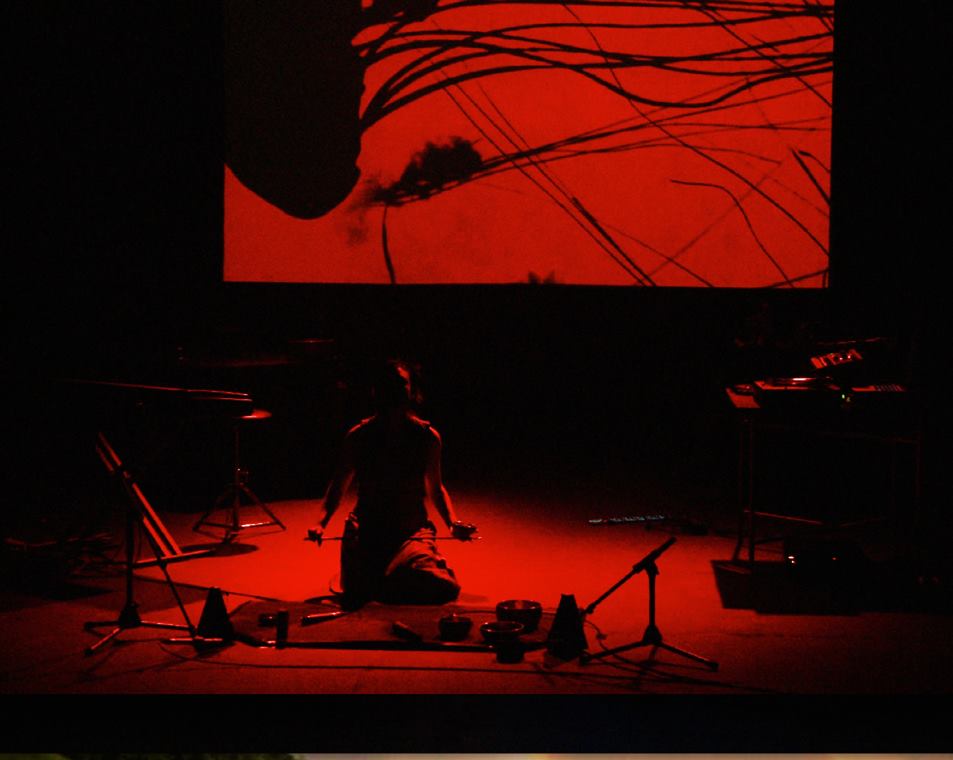

“Little Box of Horrors” from staged multimedia version of Sunken Cathedral. Video projection design by Adam Larsen. Photo: Singapore Arts Council

Do you think about building an audience or fitting into a niche?

I’ve always just been pretty set on creating my own niche instead of finding one. My music lives very intentionally in the realm between existing forms, and as a result, my fans are a pretty disparate bunch. But I think it’s representative of my disparate musical and cultural identity. There are a lot of new music people, classical people, electronic folks, DJs, producers, robotics people, Korean people, arts people, fine-art people, early music people. Church people, who understand the spirituality of music.

If anything, I would be really excited to know that there could be a bridge between all these genres. I hope that this record can be that weird bridge that allows people to go to these other genres. That would be a huge honor. I think when you leave the definition wide open, people can find their own experience in it. That’s what makes me happy as an artist. I won’t tell people how they should feel in the musical space. I want to simply create the space, have people enter it, find their own experience in it and maybe walk away with something profound and significant for themselves — but that’s not something to be dictated. It has to be unique for each individual. That’s the true test of whether the personal has become universal.

Fellows Friday is a weekly column introducing you to a member of the TED Fellows community. Read more about TED Fellows »

Comments (13)