Gabriel Barcia Columbo creates immersive experiences that raise a chuckle—and make you think. Photo: Ryan Lash

Vending machines that sell human DNA. People trapped in jars and blenders. Bottles of perfume that smell like burning books. You have to expect the unexpected with Gabriel Barcia-Colombo, a New York–based artist who works with film, electronics, performance, biomaterials and more to create mind-bending interactive artworks.

His latest piece, “New York Minute,” confronts commuters in a subway station with slow-motion, large-screen portraits of New Yorkers at play. As this work debuted in the Fulton Center subway hub in New York, we asked Barcia-Colombo to take us on a tumble down his own private rabbit hole — past dreams of derailed roller coasters, mummified spaghetti brains, and other weird wonders.

Tell us about your latest work.

I just launched “New York Minute,” a 52-channel video art piece. It’s a 60-screen installation at a new subway station in New York, and it features super-slow-motion portraits of New Yorkers. It’s about trying to get people in this new subway station to slow down and look at art on the wall. The characters that you see on the street when you used to look at people on the street. So every ten minutes, all the screens in the new Fulton Center play all 60 of my 30-second videos of New Yorkers doing a slow-motion dance, all at once. I’m doing a lot of performances in New York, and a lot of larger public works. I decided just last year that I want to focus on public pieces.

“New York Minute” features 52 slow-motion portraits of New Yorkers doing everyday things. This subway installation points out the things we miss when we rush around the city at a frantic pace. It was commissioned by the MTA Arts & Design program.

And you recently created a public performance about banned books at the New York Public Library that was written up in The New York Times. What was the idea for it?

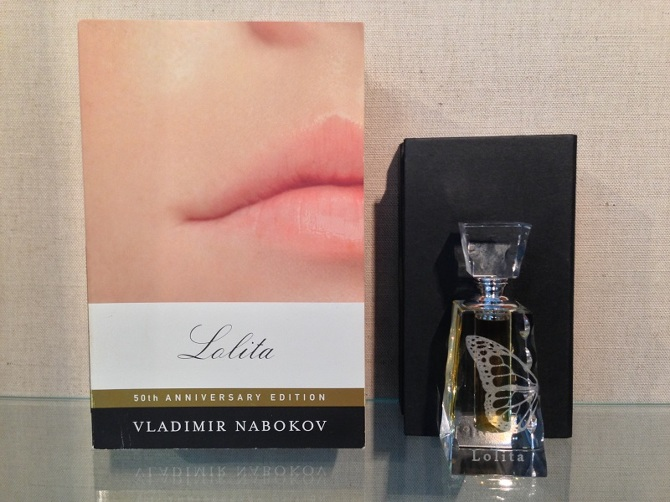

That was an installation in the mid-Manhattan branch called the “Secret Society of Forbidden Literature.” There were two components. First, I put LED signs in the windows that played lines from famous banned books, viewable from 5th Avenue. And then I made custom perfumes, based on the plots of famous banned books. So I made a Fahrenheit 451 perfume that smelled like burning books, and a Lolita perfume that smells like teen romance (a lot of candy and fruit), and a Brave New World perfume that references a passage about a machine called the scent harmonium, which creates smells for the future. I created the smell they describe in the book for Soma perfume. It smells like metal and spice.

For the “Secret Society of Forbidden Literature” at the New York Public Library, Barcia-Colombo created perfumes from passages in once-taboo tomes. Lolita’s essence is of young love — fruit and sweets. Photo: Gabriel Barcia-Colombo

Then, for one night, we gave a performance. I collaborated with a theater director named Benita de Wit for the piece, in which each member gets a fake library card, gets initiated, and takes a vow to protect the banned books. Then each person was assigned a book. A character would come out and pull each audience member into the library somewhere to perform a scene from the book, as a character from it. It was a one-on-one performance. In fact, we conceived the idea as a sort of literary lap dance.

Above, sneak a peek into the “Secret Society of Forbidden Literature,” an immersive performance by Gabriel Barcia-Colombo and Benita de Wit about the history of banned books in the New York Public Library.

That sounds like an amazing experience. What were some of the characters?

One was a kid from Lord of the Flies, who built a little tent for you, you’d huddle inside together pretending you’re on the island, and he’d recite part of the passage to you. For A Clockwork Orange, a doctor would grab you and take you into an elevator. As you went up, she’d ask all these questions, and then put you in front of a window, and give you headphones playing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. And when you looked into the street, you’d see a guy dancing perfectly in sync with what’s playing in the headphones.

For Alice in Wonderland, the caterpillar would hand you a pill: “One of these will make you smaller, one of these will make you taller.” It was just a Tic Tac, but people were unsure whether they should eat it or not. I like the idea of doing immersive projects where there’s no boundary between audience and the actor.

The overall idea was that in the secret society, they’d found other ways for you to ingest books, whether through propaganda — the LED signs — or via the sense of smell, or through sound, in the theater component.

Under a tent in Lord of the Flies for the “Secret Society of Forbidden Literature.” Photo: Yu-Ting Feng

Where do you get such wacky ideas?

I get them usually from walking around the city and looking at people, and then seeing all the things that people seem to miss in the city — street interactions, that kind of thing. Most people are looking at their phones nowadays, where they don’t notice there’s all this crazy drama that’s happening around them. I’m also influenced by dream imagery. I have a lot of crazy dreams all the time. I go to these places that don’t exist, but I go to them over and over again in the dreams. I have a dream where I go to the same amusement park over and over again. There are these different rides. But every time I go on them, something goes terribly wrong — they’ll catch on fire, the track won’t be finished.

You should make that.

I’ll work on it. I could all it “Danger Park.” I grew up in Los Angeles—that could be why there’s all these amusement park dreams too. And I go to Coney Island every weekend in the summer. I’m actually teaching a class right now on how to make a haunted house. It’s my favorite class to teach, because it’s part acting and part immersive theater, using technology — remote control lighting, soundtracks for spaces, interactive motors — to create immersive effects.

Above, see “Animal Chordata,” a collection of Barcia-Colombo’s friends captured in jars.

Where did you get the idea to capture people in the jars, blenders, and so on?

I went to film school at USC and made a bunch of films – but the medium felt very static. It’s this experience where you’re sitting there and watching this art form take place in front of you. You have emotional interaction, but you don’t have any physical interaction with it. I wanted to make filmic experiences, but things that you could actually interact with physically in some way — whether that’s touching something, or affecting a material by moving in front of it, or using sound sensing.

So I started thinking about what you could do with characters in 3D space, in real life. As a graduate student, I went to the Interactive Telecommunications Program at NYU, where I now teach. There, I learned to work with sensors and microprocessors. I started incorporate the technology into film, creating pieces that were half cinema, half interactive-art hybrids. I filmed my friends, and then I projected them into these jars. Then I used a proximity sensor that would trigger different reactions, so it’s as if the people can see you from inside the jars. I worked on this series of pieces for about five or six years. Now I’m doing different pieces that are similar in style, but not with projection into glass.

I have those pieces in my house now. It’s funny, because none of the group of people I filmed in that first series live in New York anymore—a lot of them have moved away. So it’s this nice memorialization of them—and of my life—at that time.

The DNA Vending Machine dispenses real human DNA specimens for $100, payable by credit card. Photo: Gabriel Barcia-Colombo

One piece you talked about on a TED stage, the DNA Vending Machine, sells real DNA samples from actual people. Does this present a privacy issue?

There are no names, but each specimen comes with the image of the donor. It’s a little creepy, but I can get your DNA right now if I want. It’s not hard. I could take a strand of your hair. DNA is all over cigarette butts.

Having said that, if there are any creepy requests, I don’t respond to them. I had one guy who wanted to buy the whole machine, and I didn’t really understand what his motivations were because he wasn’t an art collector. It just didn’t feel right. This piece is so much about privacy, it does creep me out if somebody wants to buy the whole thing. But the fact that people want to buy individual ones is, I think, an interesting phenomenon.

[ted id=1942]

So what’s the going rate for DNA in your vending machine?

The initial price is $100 per package, payable by credit card. People bought them all, but after my TED Talk went online, I got a ton of requests for more. I’ve put them on hold for now, because I want to figure out what the trajectory of that project is.

The point of it is that you don’t know what you’re getting. Every package is equal, and you find out afterwards. It’s like a Japanese blind-box toy. After that talk went live, I got emails accusing me of being a terrible human being, or even being a serial killer planting evidence. But part of the point was to get interesting reactions from people. It generates fear because privacy is such a big deal right now. In a way, I’m asking, “What is going to happen with this?”

[ted id=1508]

If people are nervous even about putting photos on Facebook, then it does seem a stretch to sell one’s DNA in a vending machine.

But legally, the United States owns the DNA of its citizens. When you are born, the government can take your DNA legally, and put it in a DNA bank. If you have a birth certificate, the government can take your DNA. And if you are suspected of a crime and are a foreigner, they can take your DNA as well.

Do you know the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks? It’s a famous court case about a black woman whose cells were propagated for scientific research, without her knowledge. They made a ton of money off her DNA, and she and her family received nothing. So the question is, if someone buys DNA from the vending machine and uses it to create a new drug that cures a disease, what would that mean?

Do you have a particular artist that you would point to as an influence?

I’d say Marcel Duchamp. I read his biography recently, and we have very similar viewpoints on life. I also relate to the way he uses humor, while making serious points at the same time. A lot of my work also use ready-made or found objects. The blenders that I used were all found objects. I use a lot of older objects in my work, and kind of breathe new life into them with technology.

Above, watch “Blend,” a 1950’s housewife trapped in a blender.

To bring it back to your blender projections and New York Minute, what about video art?

Nam June Paik — sort of the godfather of video art — is an artist I like a lot. He was one of the very first video artists in the late ’60s. It’s still an art form that is challenging. Most people still don’t understand how video can be art. I think that’s happening with new media art now too. Code is becoming art and people don’t know how to treat that.

Even the hardware involved is novel. Some of the pieces of equipment that I use in my pieces are now being acquired by the MoMA as design objects — like the microcontroller I use, the Arduino. Just as Duchamp challenged people to look at a bicycle wheel attached to a stool as an artwork, video art is now challenging people to look at a medium from a new perspective.

Above, watch “Tube II.” Two people emerge from a television as static and struggle to make it in the real world.

It’s odd that it started so long ago, and people are still wondering and scratching their heads over it.

But really, the timeline is right for the acceptance of video art as screens get cheaper. Everyone will have giant screens. There are already services that sell art just for iPads and iPhones. And they’re digital editions. I think that in the future, within the next two or three years, you’ll have a digital canvas in your house that will show digital work, rather than having a painting. At that point, video- and code-based artwork will be perfect.

I have all these crazy movies that I used to make when I was a kid. My sister and I used to stay home from school and shoot VHS films. For example, at 8 years old, I made a video explaining mummification to my class. I mummified my sister — literally wrapped her in toilet paper — and filmed taking her brains out through her nose, with spaghetti. I actually put spaghetti in her nose and pulled it out. So the performance and the filmmaking part was always there for me. It’s just now there’s different media to express the same sort of ideas — whether it’s using biomaterials or live actors or projections on walls.

Comments (3)