Shigeru Ban was commissioned to design and construct the Christchurch Cardboard Cathedral in New Zealand after the deadly earthquake of 2011. Here is a view of the inside, shot in 2013.

“I was disappointed in my profession,” says architect Shigeru Ban in today’s talk, which he gave at TEDxTokyo in May. As far as he’s concerned, architecture has lost its way.

Shigeru Ban: Emergency shelters made from paper

“We are working for privileged people, for rich people, for government and developers. They have money and power, and those are invisible, so they hire us to visualize their power and money by making monuments of architecture.” Ban, instead, has committed himself to creating buildings that can truly be useful — whether or not they’re permanent fixtures on a horizon.

Shigeru Ban: Emergency shelters made from paper

“We are working for privileged people, for rich people, for government and developers. They have money and power, and those are invisible, so they hire us to visualize their power and money by making monuments of architecture.” Ban, instead, has committed himself to creating buildings that can truly be useful — whether or not they’re permanent fixtures on a horizon.

Ban first began experimenting with constructing buildings from paper tubes in 1986, and he’s continued to test new ideas of form and material ever since. For Ban, good architecture must answer questions of utility and sustainability even as it delights with aesthetics. Somewhat surprisingly, given the apparently transient nature of so many of his chosen materials, his buildings have proven long-lasting.

Here, take a look at a gallery of images he put together exclusively for the TED Blog.

“I like to build monuments that are beloved by people,” Ban says. Here, a look at the exterior of the Christchurch Cardboard Cathedral in New Zealand.

Temporary housing. hastily erected after disaster. often allows only a sorry approximation of “real life.” Ban built these multistory buildings from shipping containers to house residents in Onagawa after the tsunami hit Japan in 2011.

After the Japanese tsunami in 2011, many people were evacuated to local community centers. The scene was often one of chaotic disarray. Ban’s solution was simple: to give evacuees at least a sense of individual space by building partitions from cardboard tubes and curtains.

When an earthquake struck Haiti in 2010, Ban drove six hours from Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic to get to the stricken country. There, he worked to build 50 shelters from local materials.

The 2008 Sichuan earthquake killed 70,000 people in China. Ban traveled with his Japanese students to work with their Chinese counterparts on rebuilding. “In one month we completed nine classrooms,” he says. This included the Hualin Paper Elementary School, shown here.

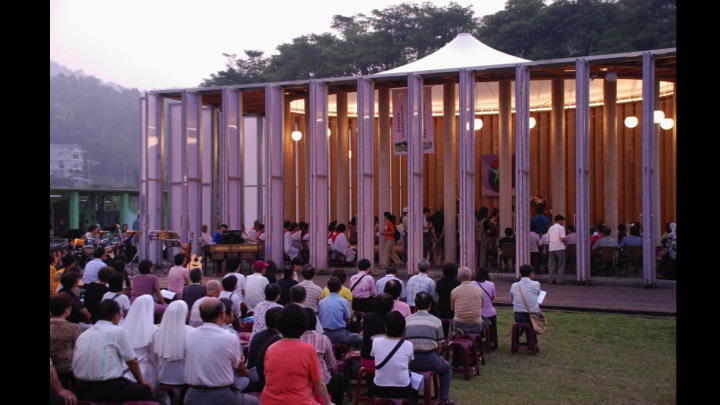

The Paper Dome was originally built in Kobe, Japan. But after a big earthquake hit Taiwan in 2008, Ban and his team dismantled it and sent it to be reconstructed by volunteers as a permanent structure there.

Ban does not always resist working for large organizations or clients. He describes this offshoot of the Centre Pompidou, which he built in Metz, France in 2009, as “a big monument for government.”

Ban says he was couldn’t afford Parisian rent when he came to the city to work on designing the new Centre Pompidou. So in 2004, he built his own office on top of Richard Rogers’ iconic building. “We stayed six years without paying any rent,” he recalls in his talk. Only one problem: Anyone who came to see him had to pay the entrance fee for the museum.

After a big earthquake in Italy destroyed many large concert halls, Ban was commissioned to build a temporary auditorium — out of paper. Here, two images of the Paper Concert Hall L’Aquila, built in 2001.

“What is permanent? What is temporary? Even a building made of paper can be permanent as long as people love it,” says Ban. Shown here, some of his perma-temp structures: the Paper Log House built in Turkey in 2000; the Paper Log House built in India in 2001, and Kirinda House, built in Sri Lanka in 2005.

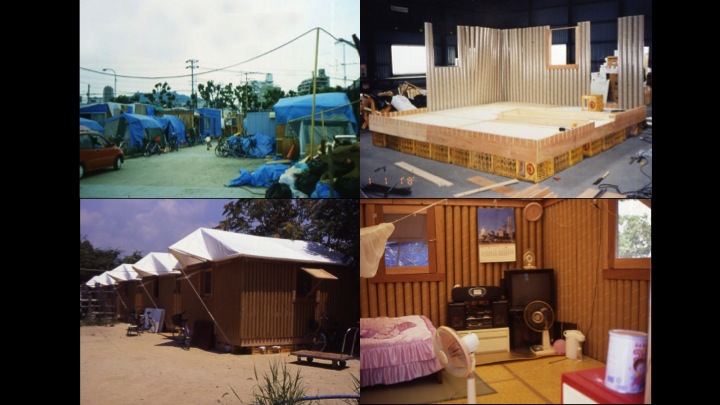

“The collapse of buildings kills people; that’s the responsibility of architects,” says Ban. But all too often, architects eschew relief or disaster work for more obviously prestigious projects or, as he puts it, “working for privileged people.” These images show one of his first projects working for the displaced, the Paper Emergency Shelter for UNHCR, Rwanda, he built in 1999.

After a huge earthquake in Kobe in 1995, Ban proposed a new design for a local church to the presiding priest … one he wanted to make from paper tubes. “Are you crazy?” the priest asked him. Ban didn’t take “no” for an answer, but instead first constructed smaller buildings, and slowly persuaded the priest his idea wasn’t at all crazy. The resulting church stayed in place for ten years.

Comments (16)

Pingback: ID | Pearltrees

Pingback: .caisson documents | Pearltrees

Pingback: تعرف على أبرز المباني المصنوعة من الورق المقوى | صور العرب

Pingback: تعرف على أبرز المباني المصنوعة من الورق المقوى - الأسبوع الإخباري

Pingback: تعرف على أبرز المباني المصنوعة من الورق المقوى | تويتر العرب

Pingback: Japanese Architect Lives to Create Cardboard Buildings for Disaster Stricken | Japan Realm

Pingback: Shigeru Ban’s wonderful speech in TED

Pingback: Check this out: Buildings made from cardboard tubes, Shigeru Ban | naïve to cultured

Pingback: Friday Link Fest…* | rethinked…*