Tell us about your life as a dancer.

I grew up in Alexandria, Virginia, where I started dancing when I was three and a half. I’m an only child, and my folks wanted me to do something with other kids, and a dance school was really close to my house. I liked the class, and it kind of snowballed from there. In 1989 I saw the movie Tap, which starred Gregory Hines and Sammy Davis Jr. and a ton of the old guys — Jimmy Slyde, Arthur Duncan, Bunny Briggs, Sandman Sims, Henry LeTang, Steve Condos, Harold Nicholas. They each had a very evident persona as they danced. And I was hooked. I wanted to do what they were doing.

So you saw each personality coming through in the dance?

Yeah. There’s a scene in the movie called the challenge scene, in which each one of the old masters comes out and takes a little segment. It’s theirs, and they dance. And each guy does something so specific and so unique to their persona, it wasn’t like they were doing something that was even related to one another stylistically. That was really intriguing for me because I was coming from a dance school culture, in which everybody danced the same. It had such a sense of freedom and personal expression. I was really attracted to it. So that was the hook. And I had it in my mind from when I was 10 that when I was 40, I hopefully would have had a successful tap dance career and would be able to meet Gregory Hines and be able to tell him that he was such an influence.

Within a year, I met Gregory and I met Savion Glover, and I started working with Savion in a couple residences he did in DC. My plan was fast-tracked.

How did you end up meeting them so young?

I ended up getting hooked up in a rhythm tap company in DC, and the artistic director told me about these workshops they were teaching in New York. My folks said, “No problem. We’ll drive up and you can take the classes.” I almost had a breakdown on the way up because I had four hours to think about the fast-tracking of my life goals.

Your future was coming at you way too fast!

Yeah. It really, really was. It was very emotional. I’d had my life planned out. “I have 30 years to get to this point, not four hours to think about it.” That led to a working relationship with Savion. He started an all-male dance group called Real Tap Skillz. We worked a little bit — minor touring — and Gregory started mentoring me for a number of years before he passed away. And through Gregory and Savion, I got to meet a lot of the old guys that I had seen in Tap. And they took me under their wings.

Gregory and Savion were very generous and very gracious that way, that if they were in a room and you had a question, they would point you to one of the older guys and say, “Go ask them. Don’t ask me.”

That kind of generational respect is very much ingrained in the tap dance world because of the oral tradition. So the closer you are to the heyday of tap — or those stories — the closer you are to something that is considered real and not one or two generations removed from the actual history.

So it’s been a whirlwind. Savion started a company in 2001 called Ti Dii, and I went on tour with him for about three years. When that finished, I started my own company called Cats Paying Dues. We’re going into our eighth season this coming September.

Can you tell me about the oral tradition and how you’re working to keep it alive? And is there still a big tap movement?

It’s more than it used to be. It’s had a pretty marked resurgence since the 1970s. In terms of trying to keep the oral tradition alive, that’s probably one of the more challenging things, particularly in a digital age, because the idea of having a personal relationship with someone and backing content with an emotional connection — which is really what an oral tradition is — you don’t get a lot of opportunities to do that. Most people would rather spend time on YouTube looking at footage and learning the content than building a relationship that with it comes a sense of responsibility to the person as well as to the craft.

To the tradition, in other words?

Even more so. It’s almost like doing something because your parent or your grandparent would like you to. It’s in honor of them as well as because you enjoy it. So there’s love in multiple directions.

I do get a chance to dive into that kind of a relationship with my company members. We spend a lot of time together during the rehearsal process. The content I deal with is very much derivative of experiences I’ve had with the masters and with Gregory and Savion. And then I also allow my company members to see my process. I’ll choreograph pieces while everybody’s in the room. That way, they can see what I’m thinking and what questions I’m asking. Hopefully that gives them some sort of insight into my own personal experience.

My company’s only six to nine dancers depending the season, so in terms of trying to take the knowledge to a greater populous, I started the Tap Legacy Foundation in 2002 with Gregory Hines. The organization is really built to support the restarting or the reigniting of the oral tradition. What we do is either produce events or provide points of engagement that will hopefully start conversations and spark interest, so that the impetus comes from the person who has the interest. That way, the person who has the story feels more willing to engage, because they’re being asked a question by someone seeking knowledge. We’ve done everything from tap jams to Lindy hop parties to photo exhibitions.

In terms of information, we’re building a digital archive that’s open and accessible to as many people as possible, that includes as much media as we have — programs and posters, reviews, video, pictures — which will allow for personal exploration of the form in lieu of the fact that a lot of the masters are passing away. The Tap Legacy Foundation is looking for a physical space for this.

What did the masters teach you? You said in your Fellows talk that they said, “Dance from your heart.” So did they critique you on your technique? And at what point does personal expression come into it? What’s more important to the old masters?

For the old masters I think there’s a balance. Depending on who you talk to, some of them were trained dancers, some of them were not. And by trained, I just mean they had classes from a teacher while some of them were trained on the street, so to speak. The bottom line is basically that you have to have enough technique to get your point across. So whatever it is that you wanted to say, you had to have enough skill to say it for somebody else who is not a tap dancer to understand it. As for how you got there, every master had a different idea as to the appropriate skill set, content or approach to get to that point.

So you sit with Bunny Briggs, he’d tell you one thing. Sit with Jimmy Slyde, he’d tell you something else. Sit with Henry LeTang, he’d tell you something else. The kind of dancing that they developed over the course of 70 years was evidence of each dancer’s unique personal experience. So for me it became a challenge to try and figure out, Okay, if everyone is telling me something and it’s dealing with the same craft, but they’re not saying the same thing, what’s the same? What is the underlying truth of the entire craft?

What about the fundamental building blocks of tap dance? You’ve got a language.

Yeah. We have a language. The language is sound and movement. Both of those things have to be there. The movement begets the sound. And then the sound in turn triggers, maybe, what comes next. It depends on what you’re thinking or what inspiration comes first for the dancer. Sometimes for me it’s a rhythm, it’s a song. Other times it’s a picture that I’m trying to produce. It also changes whether I’m dancing as a soloist or whether I’m choreographing for my company.

Tap dancers juggle more than one thing at the same time. We’re dealing with spacial awareness as a dancer does, but also auditory feedback like a musician. So the awareness of tone and time and having to deal with the audience’s perception of music or their stereotypes or the ideas of music that they already have and how we can connect to them that way — and whether we look good or not while doing that — becomes either an artistic choice or something that we get judged on.

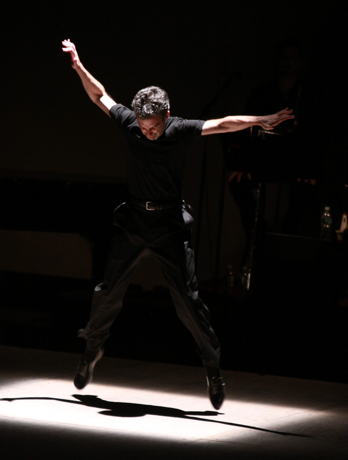

Do you improvise on the spot when you perform, or do you choreograph everything?

As a soloist I tend to be more of an improvisor. So everything I did at the Fellows performance was improvised, in terms of my dancing, but the talk was scripted. I try not to lock into one process because that gets boring. So I allow for as many points of inspiration as possible, and then just getting into the flow of what my body already knows or what it already likes to do, and then trying to break those habits to see if I can learn something else.

Did you enjoy Wayne McGregor’s improvised choreography demonstration at TEDGlobal 2012?

Oh, it was great. I thought his pacing was extremely fast. I actually asked him about it, and he said he’s normally fast, but that was probably quicker than even he likes to work. I think it was just because of the TED clock ticking down. But his dancers’ ability to retain the choreography was really cool to see. I tend to lean more toward dance that is storytelling based than something that it more abstract. So the cultural relevance of dance really goes back to times where there was a town square and dances were used to express aspects of the human condition. That’s where I really enjoy the function of dance and where I really feel at home.

How are you feeling about being at TEDGlobal and being part of the Fellowship?

The Fellowship is amazing. We’re all sharing this wild ride together, and coming from such a wide array of spaces, it’s nice to be able to share our stories and to see the different experiences that everybody has had to get here.

TED is amazing; the talks have been great. It’s very analytical here at the conference. I think it’s interesting to see the crowd’s reactions to artists and to people who are of a creative nature. They’re super appreciative and very engaging. But I always find myself on the “let’s get away from the computer screen” side of the debate, on the balancing end of the analytical minds. Let’s get back to interpersonal relationships and real face time and matters of the heart.

Comments (6)

Pingback: The music of sign language, a computer of water drops: 21 TED Fellows share ideas that swim against the tide | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: The music of sign language, a computer of water drops: 21 TED Fellows share ideas that swim against the tide | Lifespace connect

Pingback: Give me your fussy, your bored, your hard to buy for: the TED Fellows gift guide | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: Tap: Presentations & the Public Eye | PAA News

Pingback: reBlog from danceadvantage.net: Teaching Tap Improvisation: Exercises for Beginners | PAA News

Pingback: Andrew Nemr @ TED Blog | shufflin'