Meklit Hadero’s voice is earthy and soulful, sinuous and untethered, and she’s about to unleash a new album on the world. She has just launched a crowdfunding campaign for her second solo recording, We Are Alive, and is currently touring the East Coast of the United States.We caught up with her between shows to ask about her musical vision and her latest news, including an exciting new initiative promoting food sustainability in the Nile basin.

You’re often billed as Ethiopian-American singer. Did you grow up in Ethiopia? Tell us about your journey to becoming a singer-songwriter.

I grew up all over the place. I was born in Ethiopia, and left when I was about 2. We went to Germany briefly and from there to DC, Iowa, Brooklyn, Florida, Seattle, now ten years in San Francisco! I like to say that my upbringing was a good training for life as a touring musician.

I studied political science at Yale, but I always thought of a liberal arts education as developing a relationship to language, writing, and complexity, learning to take streams of thought from multiple disciplines and develop your own opinions about the world, to engage with information and culture in a present-time way. Even though I’m no longer in the field of political science, those meta-ideas are ones I put into play every day.

After college, and after a few years in Seattle, I moved to San Francisco and found the Red Poppy Art House. That tiny little arts and culture hub was my introduction to artists and musicians from around the world who were thinking big and making work with substance. I started organizing there, and ended up co-directing the space for two and a half years. The community around me really supported me in making the transition to being a full-time artist.

Do you identify strongly as both African and American?

Yes, absolutely — I feel deeply African and deeply American. I was born in Ethiopia, my parents are Ethiopian, so I grew up in many ways steeped in that culture. At the same time, I was raised in Brooklyn, equally surrounded by early hip-hop, street-level jazz, and Ethiopian classics. I like to say I walk the road of hyphens. That’s actually where I’m most comfortable, in between and celebrating it. I grew up always wondering where home was, especially because we moved so much. It became a wonderful driving question in my music, especially early on.

I remember the first time I went to Ethiopia as an adult. It was me and my mother. Growing up, she always referred to Ethiopia as “back home.” Then when we were in Addis Ababa together that first trip, she kept referring to the States as “back home.” It was then that I realized just how fluid that phrase and idea were. It didn’t mean a place — it meant a state of being. And that freed me in a way to both accept the searching, and let go of it too. Culture is funny — there are no firm lines, only fine ones.

Above: Watch “Leaving Soon” — a music video from Meklit Hadero’s first album, On A Day Like This.

You’ve just launched a Pledge campaign for your new album. What is it about, and how is it different from your previous work?

We recorded in November and the new album, titled “We Are Alive,” will be out March 18. The PledgeMusic campaign just launched earlier this week. We really had fun creating the campaign and got as creative as we could with the perks, including visual art, homemade covers, songs written just for you, all sorts of stuff!

The concept that ties the whole thing together is simple. As hard as life gets, and as sweet as it gets, we are alive. It is the through line in all our experiences. It’s an anthem that celebrates the ups and the downs as equal parts. Sugar and salt. Rock, paper, scissors. After my first solo album, On A Day Like This, I spent a lot of time on side projects. You see, every artist has their whole life to write their first solo record, and they usually have a year and a half to write their second one. I didn’t want to fall into that trap. I wanted to take a few years to explore and experiment. We Are Alive brings all that time of experimentation together into one cohesive sound. I’m really proud of how this turned out. It feels really good.

Your influences are very wide – tell us about some of your favourite music. Can you tell us about how you found your own unique style and voice?

In some ways, I think part of finding my own voice was starting out rather late as a musician. I didn’t begin taking voice lessons until I was 24. I wrote my first song at 25. It gave me time to find out what it was I wanted to say, and to make sure that music was the right medium. I always loved music. Growing up, my very favorite was everyone’s favorite, Michael Jackson. These days, my tastes run much wider, which matches the way our culture is evolving. Nobody listens to just one type of music. Everyone’s iTunes has many genres, eras and styles represented. I love artists like Lila Downs, for her incredible tone range; Caetano Veloso, who taught me you could write a song about anything; Aster Aweke, whose emotive power is humbling; Arcade Fire, who nurture my inner epic; Leonard Cohen, who makes me want to write every time I listen to his voice. Many of my friends inspire me deeply as well, for example TED Fellows Susie Ibarra and Somi, who are both incredible!

Tell us about the Nile Project. How did it start, what is its aim, and where are you with it now?

The Nile project began in August 2011. My dear friend Mina Girgis, who is an Egyptian ethnomusicologist, and I had both been to an Ethiopian music concert in Oakland. Afterwards, we were sharing a beer and wondering why we had all this access to one another’s cultures in Diaspora, but not on the continent. We thought to ourselves, “We share the river, and yet we don’t know one another. Why don’t we start a project that allows us to get to know one another across the Nile river basin?” The project began around questions of cultural curiosity and communication. Very quickly we realized it was much bigger than that. The Nile, which spans 11 countries in East Africa, was in the midst of attempting to redefine how it relates to itself and shares water, and this was causing all sorts of political tensions on the eastern continent. We realized that this was a place where music and culture could be concretely helpful in what had typically been a political story. Let’s learn more about one another, starting in the music, and from there, other sorts of collaborations become possible.

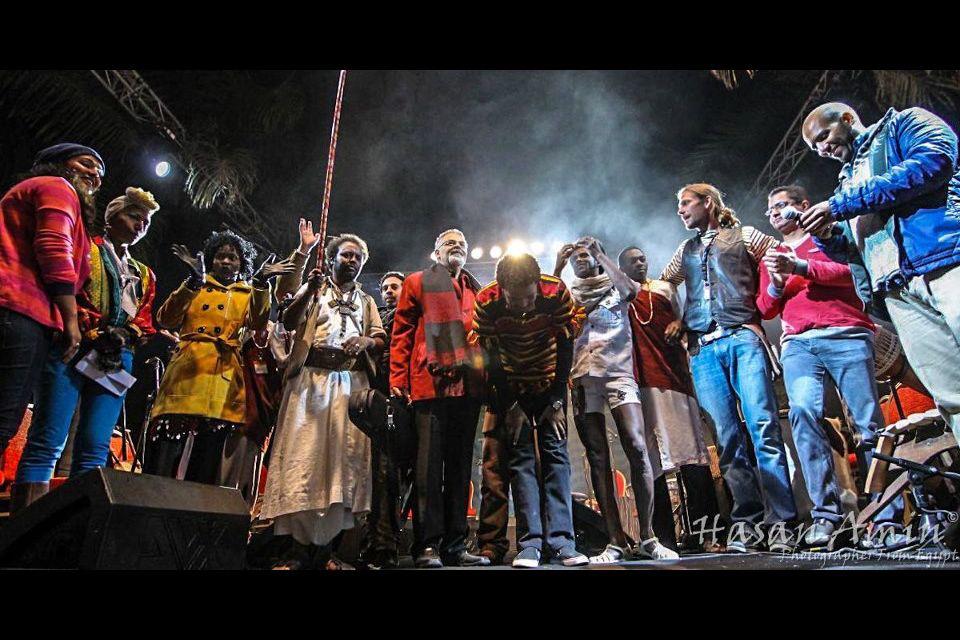

So we had our first residency in Aswan, southern Egypt, last January. Eighteen musicians from seven Nile countries got together, and created a body of music together. It was a truly beautiful moment. Musicians do make wonderful ambassadors. We are about to have our second residency in Uganda at the end of this month. But it’s a huge project that will span years. And it should. It’s a hugely complex issue, and the diversity of cultures along the Nile is unbelievable. We’re just getting started.

And the project itself is branching out and expanding, isn’t it?

Yes, this year, the Nile Project will launch the inaugural Nile Prize with the theme of “Food Sustainability.” Over the span of a year, the program will support Nile Basin university students in the design and implementation of local solutions based on principles of sustainable, community-centered design. More than just an award, the prize will guide students through a series of educational and skills-based trainings, community-focused exercises and transboundary collaborations. The intention is to build the capacity of students, civil society organizations and communities with the skills, knowledge and resources needed to collaboratively design and deliver new innovations for the Nile basin.

When we were developing the Nile Project, we were conscious that we did not want to create a situation where our audiences were inspired by the music, but then didn’t know what to do after the concert was over, the lights were on and the doors were closed. Then, in the course of creating touring plans, we realized there was a lot of interest from universities, students and professors, particularly because the project brought together different disciplines in something of a new way: ecology and environmental studies, hydrology and engineering, music, ethnomusicology, design, political science, African history, and more. From there, the program was primarily designed by Mina Girgs and the amazing team of folks working with us on staff.

What were the greatest obstacles, if any, to choosing this path?

Well for one, the music industry is in crisis. Nobody knows what’s going to happen, and all the formerly firm spaces are much more fluid. Personally, I think this is very interesting, and it’s one of the things that excites me most. At the same time, you have to live with a level of uncertainty that many people would find terrifying. Honestly, that’s one of the most wonderful things about being a TED Fellow. All of us are immersed in work where we are making our own paths. It means a lot to be involved in a community where we are walking together, despite being in different disciplines. It gives you strength.

What are you most excited about in life?

Actually I get excited by little things … Every new song as it arrives, every show where you reach a new improvisational height, every time the audience sings their heart out in a call and response. I am grateful every day to be a musician, where my job is literally to go as deep as I can into into the human condition, and interpret it through sound and movement. What’s not be be excited about??

For more, visit Meklit Hadero’s Pledge campaign to pre-order her new album and get access to unreleased tracks, studio footage, photos and other goodies.

Above: Watch the video for “Neighborhood #1 (Tunnels),” created in collaboration with TED Fellow Christine Marie.

Comments (16)

Pingback: Highlighting 10 Native Ethiopians During Black History Month

Pingback: The music of sign language, a computer of water drops: 21 TED Fellows share ideas that swim against the tide | Lifespace connect

Pingback: Abraham Lincoln’s pocket watch, a musical trip down the Nile, plus a tasty menu á la TED - Social Nurse Web

Pingback: The TED Fellows 2014 holiday gift guide | TEDFellows Blog

Pingback: Meklit Hadero's brand new video "Slow" – and a call for your Afro! | TEDFellows Blog

Pingback: The New Album Has Arrived!!! ‹ Meklit

Pingback: Entry Test 2 ‹ Meklit

Pingback: How to grow a bone without a body | Health & Wellness Chicago

Pingback: English speakers: OTP needs you too! | Health & Wellness Chicago

Pingback: The New Album Has Arrived!!! | Meklit Hadero

Pingback: hissing lawns | Meklit Hadero at Dollhouse – photos

Pingback: Celebrating the in-between: Fellows Friday with Meklit Hadero | TEDFellows Blog