You’ve accomplished a huge amount for one so young. It probably helped that you grew up surrounded by a family of artists and musicians.

My family were always inclined towards performing and creative arts. My great-grandfather was an ancient music scholar. He wrote many books on music theory. And he was a multi-instrumentalist. He played the violin and an Eastern instrument called the harmonium, and the sarangi. His daughter — my father’s mother — followed in his footsteps and became a performer of Eastern music. She was a stage performer, and also played many instruments. Her brother is a professional storyteller, spoken-word poet, and an actor as well. My father is also a musician and a stage performer. My mother’s an artist as well as a stage performer. My sister, who is three years younger than me, is also a musician, as are my cousins. So everybody does something or the other.

When I was young, it was really difficult to get people to pay attention to me. Whatever I would do, somebody else could do that too. But that really pushed me to try to get better; I always wanted to be on the same level as my cousins. But now I just do it for myself. When I was younger I was much more competitive. I’m very grateful to have had that sort of environment to grow up in because it really helped me develop my work, and work on being a perfectionist. I enjoyed it a lot.

Do you play music with your family?

Not too often anymore. But sometimes I sit down with my uncles, and they play a few things and I play with them, and it’s fun. Mostly I play on my own, because I grew up playing Western classical music. I started playing classical piano at the age of 6. I was always messing around with instruments. My grandmother told my parents that I should get classical music training, and so I starting taking classical piano. I’m still learning.

I picked up guitar when I was 16. It was really different from piano because classical music is very — I wouldn’t call it restrictive, but it has a lot of rules. So when I started playing electric guitar, that really opened up stuff for me. There were no rules: you could do whatever you wanted. That was fun. So now I don’t prefer either style. I love both. I love classical music and other forms of music. I love writing orchestra pieces. That’s my favorite thing to do.

How did you get your first recording contract?

I was 18. I was performing at one of the venues back home, and this person from EMI was there. They liked what I was doing. They said, “Would you like to come and record?” Nobody really does anything that is risky back home. Everybody’s so afraid because most of the musicians are pretty set in their ways. They don’t want to experiment. But EMI offered me a completely different way to work. They said, “We don’t really know what you’re doing and we don’t want to tell you what to do. Just go ahead and do whatever you want.” Which I loved. There was no manager. There was nobody. I was completely alone in the studio with a very, very good engineer, who would allow me to stand on his head and say, “I want it to sound like this, I want to change that.” There was no real producer either. I was in complete control, and I loved that. So for two years I was working on music, on and off — I wasn’t working every day. When I’d get an idea I would go to the studio and start on it. Or when I conceived of a particular sketch of a beat, I’d go to the studio and refine it. I had complete freedom, which I really enjoyed. And that helped me make all my orchestra pieces.

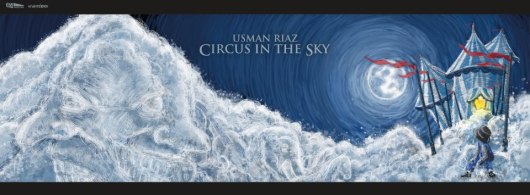

Before this happened, I was actually supposed to go to the Berklee College of Music. I even got an audition. I thought about it for a very long time and ultimately decided not to attend my audition, preferring to stay in Pakistan and record the music, get it out of my system. I’d been studying music for so long, and I had all these ideas that were building up inside, and I needed to get them out. While I was recording, I attended art school at the Indus Valley School of Arts and Architecture, studying illustration and fine art while working on recording my album, Circus in the Sky. I also took a minor in film and I learned how to manage everything for my films that I wanted to make. I didn’t want to waste time.

I’ve been doing art since I was small, so it wasn’t a problem for me to balance my painting and educational work with my music. I would finish everything in school and then go and work in the studio for seven or eight hours, recording my music, then go home and practice. It was a fun time.

Tell us about the different musical styles on Circus in the Sky.

There are 12 pieces on the album: guitar, piano and orchestra pieces. I love writing orchestra pieces, because it’s like a film. You can tell a story with it. With my guitar pieces, people get too wrapped up in the technique. They look at what I’m doing rather than what I’m playing. I’m okay with that, but I’d rather tell something with my music than have people say: “Wow, look at how he’s playing the guitar. That’s so different.” Honestly, it’s not very unique. I learned it from watching Preston Reed. Those who know the percussive style just see it as a variation of what others are doing. But people who are unfamiliar with that style of guitar playing are perhaps awed by it. I don’t really try to focus on technique or what I’m doing. I try to say something with the music.

That’s why I enjoy the orchestra pieces, because nobody sits there and goes, “Wow, look at how the violins are being played, and look at how the clarinets are being played.” They listen to it as a whole. So that’s what I want to do more of. Even my piano pieces, I start to do that. And the album actually tells a story from start to finish. Each piece borrows from the previous one and develops ideas from it — time signatures, rhythmic styles and everything — and it just builds up towards the end. I had quite a lot of fun working on that.

You were trained in classical piano, so how did you learn to write and arrange for orchestra?

Ever since I was small, my teacher always exposed me to orchestral music. Even when we’d talk about Mozart, he would say, “Yes, he was a brilliant piano player, but he wrote for orchestra.” And then we would listen to some of his orchestral pieces. We listened to Beethoven, Schubert. So I love that kind of music, and I love film scores. They amplify and accentuate so many things in film, all the emotions and the scenes.

Was the album well received by the critics in your country?

Oh, it really was well received actually. I’m very grateful that people are responding very well to it. I finished it just before I left for the TEDGlobal Conference — literally a week before. Everything was printed, the cover, the artwork, everything was ready. The final CD was done a week before I left. So it’s only been out for two months, and so far the reception has been very good.

And before that you also recorded a song called “Saeen.” From the video, it looks like you worked with a lot of musicians on it?

That piece was actually an adaptation of a song by a popular Pakistani music group called Junoon. They said, “We’d like you to do something with one of our pieces for our fifth anniversary album.” And I knew that song was really popular back home and in a few countries like Nepal and India. I knew I wouldn’t ever be able to live up to the original, so I just completely changed it and made it into a Middle Eastern orchestral piece. I replaced the vocals with a violin, creating a melody. I play almost every instrument, except for violin, on the recording, but I thought it would be pretty bland to have only me in the film. We decided to get a drum circle, and the violin player and I played in the middle of the drum circle. It was fun.

How many instruments do you play?

I’ve tried a lot of instruments. My main instruments are the piano and the guitar. But I can play the harmonica, the mandolin. I play the harmonium. I do percussion as well. I’m trained on a lot of things. It’s just fun to make sounds. I don’t really know how many instruments I play, but the ones I don’t, I really wish I could. I really, really wish I could play the violin because that’s my favorite instrument in the world. When I was younger I had a choice between the piano or the violin. I picked the piano, but I keep wondering what would have happened if I’d picked the violin.

Well, it’s not too late! You recently were in Florida, for the OneBeat fellowship, weren’t you?

Yes. OneBeat is a new initiative that was founded by the US State Department where they bring together musicians from all over the world for a bit over a month. The tagline for this tour was “32 musicians from 21 countries.” For a full month, we were together every day, and we had a two-week residency in Florida at the Atlantic Center for the Arts in Daytona Beach before touring the East Coast for two and a half weeks. It was really cool because we were really cut off from everything else. It was just us and a few guards to keep watch — two weeks where we had to just make music and work on things.

I didn’t sleep much: all the time we’d be making music and working on different ideas and concepts and ideas and working on pieces for the shows that we’d be performing. When we were all getting there, we didn’t know how all of us would gel, because there were musicians from all sorts of genres. There were Turkish musicians playing Turkish jazz and there were electronic musicians, country artists. I was the only classical musician probably.

We didn’t know how all of us would collaborate on something, because everybody was so different. But I remember, I was the first person who arrived, and the very next day I was sitting in one of the studios playing the grand piano. It was a really nice piano, and I was just practicing. And then slowly, one by one, all the musicians started coming in. We really didn’t talk much, we just all sat there. I was playing, then somebody joined me. And then another person walked in and they joined on their instrument. The percussionists walking by, they came in and started playing as well. It got to a point where all 32 of us were in that room, playing, and then the organizers also walked in, and it was a huge jam. It was a really magical moment. All of us were just playing. And we’d pause and let someone solo, and we’d pause again to let someone else solo. And that’s how we got to know each other.

Of all the fellows at TEDGlobal 2012, you seemed like the one the most affected by experience. And I was just wondering what was happening in your mind during that time, and how that’s unfolded in the last months since TEDGlobal.

TED was absolutely amazing. I think it’s probably the most fun I’ve ever had. I’d been watching the TED videos as well. I saw Kaki King’s videos, and I watched a lot of Andrew Bird performing too. It was the one-man orchestra that he did. I watched so much TED, but I didn’t know anything about the Fellows program. So when I got that email it was so surreal to me. I didn’t know something like that was there for people like me. And I didn’t even know I’d be eligible for it. I felt so grateful to be selected.

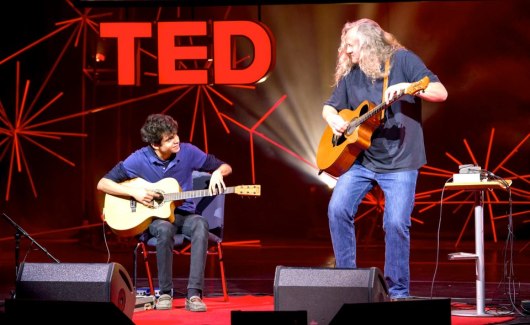

When I got to TED it was really a dream come true to be there. I love that sort of environment. OneBeat was great, but it was just music. TED is everything. And I love that, because I try to do bits of everything. I try to make my films as well, and music. So to be in that sort of environment was incredible. Everybody does everything, and there was so much to learn. And all the Fellows were amazing too. I don’t know how to describe it. I wish it hadn’t ended. I didn’t want to leave that environment because it fuels, I think, everybody’s creativity. And then, of course, I got to play with Preston Reed, which is something I’ll never forget. He has a particular way of standing — because he has long hair, he has to let the hair down his right side so it doesn’t get in the way of his eyes when he’s playing. And he always sticks his hair down his right shoulder and leans a bit towards his right side to play with his head tilted. It was such a thrill to be sitting onstage with him and watch him do that exact same move before he started playing. It was just amazing.

Has the experience settled into you, and has it informed the way that you have worked since then?

I still wish it hadn’t ended, but I have more time to reflect on it. It really has affected how I work. It’s made me a lot calmer. Before, I thought that my work wouldn’t lead to anything. And I think it’s given me a bit of a boost, because now I feel like I’m on my way to accomplishing something. And I got to be on that stage, which makes me really happy. I want to do more now, but it’s made me believe in myself a bit more.

What are you fantasizing about doing that you haven’t done yet?

What I really want to do is just keep on learning. And thanks to all the opportunities that have opened up with TED, I am in a position to do that — learn things that I normally wouldn’t have been able to. Not just in music; I’ve been in touch with all these people who, if everything works out, allow me to be in a position where I can do things that I thought weren’t possible before. I’ll be able to make more music, more experimental music, more experimental art, meet people who are doing things like that. And even opportunities for music schools — I know that.

Comments (5)

Pingback: Blue Moon Waltz: Usman Riaz’s shares his latest work at TED2014 | TEDFellows Blog

Pingback: Usman Riaz: Young Lad with a Story to Tell - The Toonari Post - News, Powered by the People!