TED Fellow Paul Wicks is changing the way patients with chronic health conditions connect with one another, and how they participate in research. Trained as a neuropsychologist — and specializing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson’s disease — Paul began using the internet in 2002 to bring together communities of patients with life-changing illnesses. He tells us about how he came to run research and development at PatientsLikeMe, an online network that helps patients learn about their disease, track their health, connect with others and contribute data to science.

Can you tell me more about ALS?

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — which is also known as motor neurone disease and Lou Gehrig’s disease — is a rare neurological condition that affects between one and three people out of every hundred thousand. The neurons in the brain and spinal cord wither and die, leading to weakness, muscle wasting and stiffness. Tragically, people lose the ability to walk, to speak and eventually to breathe. Unfortunately most people only survive between two and five years with ALS — it’s rapidly fatal. The breathing muscles deteriorate and people lose the ability to expel carbon monoxide and they become more vulnerable to infections like pneumonia. It’s a terrible disease.

What is your background, and how did you get involved with this disease?

I am a neuropsychologist by training. I studied psychology at Durham for undergraduate and then did my Ph.D. at the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College, London, where my thesis was about cognitive changes that occur in people with ALS. People had long thought ALS only affected the motor neurons that control muscles that allow arm movement, breathing, speech, swallowing and walking, but they thought that the brain was always left intact. When we think of ALS, we often think of people like Stephen Hawking, who is physically very disabled because of the condition, but who still retains his brilliant mind. He is an also an unusual example because he has lived so long with this disease.

However, over the past few decades caregivers had been reporting that some patients seemed to be having personality changes. People who were previously mentally astute were having problems doing some things that had been easy before, like multi-tasking or balancing a check book. My thesis involved doing cognitive testing and neuroimaging using brain scanners to correlate changes in the brain with performance on tests like verbal fluency, where you have to name as many words as you can starting with a given letter within a set time limit. Our study found that a subset of people with ALS actually do have cognitive problems, particularly those who have some of the inherited forms of the disease. This research has helped to overturn a lot of myths about the disease and just recently a new genetic mutation was discovered (C9ORF72) that explains a lot of what we found.

How did you go from clinical research to becoming involved with patient interaction?

Back in about 2002, well before social media was ever a buzzword, I heard about a research project called BUILD that was winding to a close. The project had created a website for the ALS patients seen at King’s College Hospital’s clinic to give feedback about how the service was doing. It included a message board-like forum, which was still being used by a few patients even though the project was coming to a close. My professor said, “Well, it seems a shame to shut this down. Can anyone take this over?” I said, “Sure, I know a bit about the internet. I’ll take it over.” I became a forum moderator. During the day, I’d go and see patients one-on-one in their homes for cognitive testing, and at night I’d see more patients online. In person I could see that they had lost the ability to speak or had a weak grip on a pen, and of course we were mostly talking about the tests. But online it felt like they could communicate much more easily; if they needed to take an hour to type a paragraph, they could, and they used assisted technology like eye blink machines or trackballs. Nowadays they use iPads with speech recognition, or eye tracking, even open source software that can track nose movements. Online they were talking about their hopes and fears, the little everyday struggles I couldn’t see for myself.

I also saw patients exchanging tips, such as how silk or satin pajamas made it easier to turn over in bed when your muscles are weak. In my day job I could only share that tip with one person a day, but online, hundreds or thousands of people could get the information.

And in the meantime, these patients are also dying. That must be very difficult.

It is. You’ll get a very close-knit nucleus of people exchanging information who also care about each other very much — then as they start becoming sick or dying one by one, the forums go quiet again. And then new people come in. Although there are some long-term survivors most people have the faster form, and so it seems to go in waves.

Do people take pause at joining a group where many people are going to die as you participate in it?

Not everybody wants to engage. Some people with ALS don’t want to know any more about it, and that’s fine. We call them “information avoiders.” Some people want to selectively problem solve, like find out from others what to do if you’re choking on water instead of waiting for the next available appointment to ask your doctor. Those are the “selective seekers.” Others can be quite positive and pragmatic — they want to know as much as they can and fight the disease on their own terms, those are called “active seekers.” They confront their mortality much earlier on. But it can be immensely hard, and people might change in their approach over time, and their caregiver might be in a different position from the patient too.

For me, I’ve been dealing with serious illness and terminal diseases for 10 years or so. So I have to have a certain amount of detachment. I’m obviously very sad when I hear about a patient I know who passes away, but if I broke down for each and every person — and I’ve known hundreds, perhaps even thousands — I couldn’t function. I feel like they’d want me to work harder for the next cohort of patients that are diagnosed today, not dwell on things I can’t control. That British stiff upper lip does come in handy sometimes.

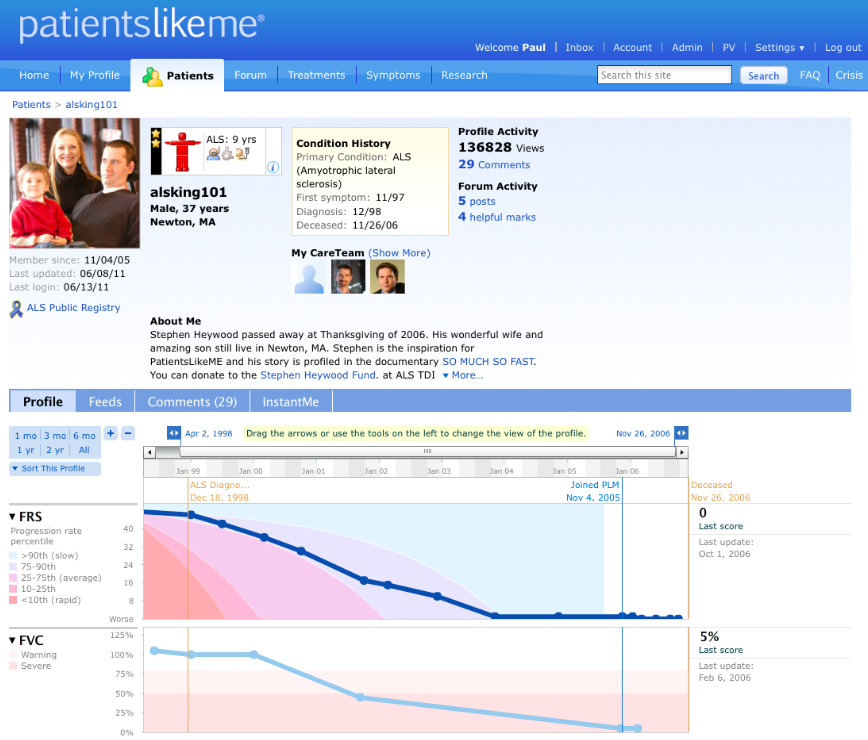

The PatientsLikeMe profile for ALS patient Stephen Heywood, for whom the site was originally founded.

How did you hear about PatientsLikeMe?

Some American patients started using the Kings College Hospital forum, and I found about it through them. PatientsLikeMe was founded by a family affected by ALS — the Heywood family, Ben, Jamie and Stephen. Stephen was 29 when he was diagnosed with ALS, and when that happened was that, Jamie, determined to find a cure for Stephen, quit his job and founded a non-profit laboratory called the ALS Therapy Development Institute (ALSTDI). The lab tried stem cell transplants, chemotherapy, supplements, even experimental, wacky stuff like Chinese herbs for many years. Meanwhile, Stephen was still living with the disease. Ultimately they thought, what if Stephen’s experience could be shared online so other people could learn from it? And what if other people shared their experiences and that data could be aggregated to learn even more?

This became the basis of PatientsLikeMe. I asked if I could join, and when I looked around, I thought it was amazing. Not only were they crowd-sourcing treatments, conditions and symptoms, they were also relying on people with ALS to track their disease. So they’d given them a measure normally only reserved for doctors — a scale called ALS functional rating scale. It’s 12 questions that ask about speech, swallowing, walking and so on, that would indicate the severity of the disease and how it would likely progress. In the past, this score would be known by the doctor and clinical researchers like me, but not shared with the patient. It always pained me that I knew a patient had a rating of a 25 or a 36, but they didn’t. It was like secret knowledge. PatientsLikeMe put this information into patients’ hands and even provided predictive background curves to see which track a patient was on. With these curves, with only a few data points, you can tell if you have 10 years to live or 18 months, or less. That’s pretty useful information about how to plan the rest of your life.

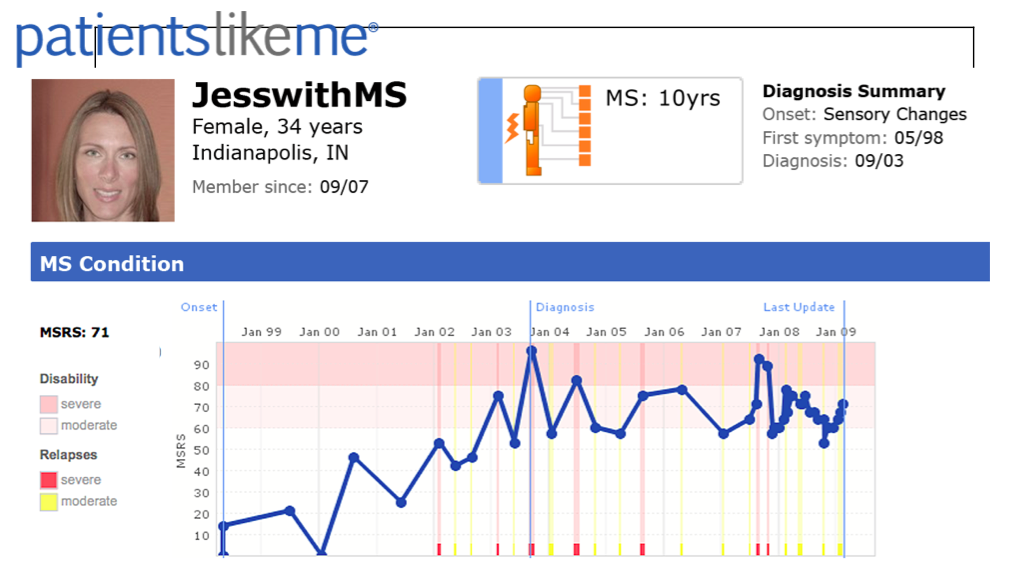

I began working at PatientsLikeMe as a forum moderator and quickly wanted to build on the community because I thought it could help every kind of patient. It turned out that there wasn’t a suitable rating questionnaire like the ALS one in every disease, so we invented one for multiple sclerosis called the MS rating scale. There was a scale for Parkinson’s disease used in clinical trials called the UPDRS that we adapted. We created new forums and communities for people with HIV, fibromyalgia, mood disorders, and later for other rare diseases. Along the way we were building new outcome scales when we needed to, starting the business up of how we’re going to make money from this and also starting the research side up.

After I graduated and got married, we moved to Boston for three years. During that time I built up a whole team of researchers and thought about how to open the site to more conditions. People would write in saying, “Why haven’t you done breast cancer yet?” or “Why haven’t you done Niemann-Pick C?” or “Why haven’t you done Sanfilippo B?” The problem was it would just take too long to build them one at a time. Our challenge was to generalize the platform so that anybody with any condition could join, and people with multiple conditions could see information on all conditions. We opened to all conditions in 2011 and opened up the floodgates.

But what about privacy? For example, your predictive curve is pretty sensitive stuff. Do people really want that opened up to the whole world?

Members have control over what they share. It’s all voluntary and self-reported. You can choose whether or not your profile is available on Google and you are under no obligation to share anything you don’t want to. Only about 13 percent of our members choose to make theirs available outside the “walls” of the site. For everyone else, you have to have a login. But it’s a tradeoff. If you believe that there are benefits, you will risk some privacy.

We’re not yet at the point where you’ll hit send and your electronic medical record from your doctor will import into PatientsLikeMe, but that’s something I’m interested in, because it would save a lot of work for people to type out dates and conditions and other information. Then again, a lot of members value the anonymity and the idea they can share things with other patients that they wouldn’t tell even their medical team, so we’ll have to see how that goes.

PatientsLikeMe has also become a source of data for research. Tell us about that.

Since the beginning, we wanted scientific credibility to be a clear differentiator of what we are doing from the last generation of message boards and forums that just generated anecdotes. That’s why we emphasize structured quantitative data supported by databases and medical ontology, in addition to open text and qualitative information.

We collect de-identified patient data and work with non-profits, academic researchers and pharmaceutical companies to better understand what’s working for patients, and what they need. We’re also a real-time research platform that’s proven you can do science on the internet. Today we’re the most highly cited patient research platform anywhere on the web. There’s about 1,800 citations to us on Google Scholar in addition to the papers that we’ve written. We’ve published over 35 peer reviewed papers in the last five years, based on data gathered from PatientsLikeMe. We did a clinical trial over the internet. We’ve developed new outcome measures for MS and ALS and Parkinson’s. We do predictive modeling. We’ve built a tool that can match patients to clinical trials anywhere in the world, for which they might be eligible. We’ve discovered some important things about diseases. For example, we’ve found that if you’re going to get ALS in your arms, you’re more likely to get it the same side as your dominant hand.

Another thing we’re establishing is that using the platform itself helps patients get better. We’ve published a couple of studies now that suggest that people who use PatientsLikeMe get better outcomes because they communicate better with their doctors and get support from each other. Incredibly the secret ingredient wasn’t just the platform, it was the connections patients were making with one another — we even found a “dose effect curve” for friendship.

So given that PatientsLikeMe is voluntary and self-reported and you’re using the information for research, how do you verify the information people are volunteering?

You have to choose your targets and you always have to put a lot of caveats on interpretation. So the first important question is, how do you know they’re patients? And the answer is, right now we don’t. People could say they have MS and we have no way of telling if that’s true or not. To check that would be hugely time consuming and might change the social contract of the site, essentially saying, “We don’t believe you, prove it.” But unless you happen to have Munchausen Syndrome or some sort of Factitious disorder, which is quite rare, you probably aren’t going to do that. Today there’s just no direct benefit for anyone in doing that, but of course as we grow, that might change over time. So we are looking already at physician verification.

There is also a much bigger issue about bias, and we’ve done a lot to to show where the biases lie, for example, that this group is slightly younger, or slightly more female than male. That skew is different for every disease; in Parkinson’s disease we have the young onset population not the elderly; in epilepsy we have adults not infants or seniors; but in something like MS or fibromyalgia we’re only off the population norms by a little and you can control for that. In many diseases we have more registered patients than any other database in the world, so you’ve got to ask the question: biased compared to what?

How is PatientsLikeMe funded?

We’re very open about the fact that we are a for-profit company, although I describe us as a “not-just-for-profit”. As well as the academic collaborations work, I’m also responsible for scientific collaborations with various commercial partners for which we get paid. We’ve now worked with nearly every top-20 pharma company. For instance, we worked with the drug company UCB to build an epilepsy community, we’ve worked with Novartis in exploring treatment barriers in MS, we’ve worked with Merck on psoriasis and we announced a partnership with Boehringer-Ingelheim while I was at TED2013, focusing on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis — a rare lung disease with no known cause, treatment or cure. It’s similar in some ways to ALS, and it uses some of the same tests.

So if pharmaceutical companies help to fund different wings as you build, do they get access to patient information?

There are two models. One is getting access to the de-identified aggregated data that we’re collecting already; the other is we do studies for them to go out and collect new data. The reason they want that is there are a lot of regulations (there for good reasons) that mean pharma finds it difficult to listen directly to patients, but they can have researchers in the middle. So we’ve done a number of studies listening to what bothers patients and helping to refine those into new patient reported outcome measures for them which might eventually end up as a measure in a clinical trial.

We do all we can to make our members aware of our funding model. Unlike many other sites, there are two things we do a bit differently. One is there’s no advertising on the site for pharmaceutical products. I think that advertising can put undue influence on people to go for treatments that aren’t necessarily the most suitable for them or that are more expensive. The second thing is transparency. So if I’m doing a survey for Novartis, it will say, “Dear Karen, PatientsLikeMe is partnering with Novartis to find out about any issues you have while taking the medication.”

The third thing is we give patients the results back as soon as we can. So if you do a survey today and I have the results in two months’ time, I would give you back a snapshot of the results at the same time I give it to the client. They can clearly see the value of taking part then. And then finally, we always publish open-access wherever we can, so that everyone who took part in the study can read it. So all the patients immediately benefit from the information that comes from any study they participated in.

Is there controversy about patient-led forums and giving patients so much information about themselves?

Yes. Some clinicians have speculated along the lines of, “If patients talk to one another on the internet, they might misdiagnose themselves and contradict me. Or they’ll order experimental treatments off the internet and shoot it into their eyeball or something and then I’ll have to pick up the pieces.” In practice though, other than inconveniencing doctors by asking more questions (which they should be doing anyway), there is very little evidence of harm. Unfortunately there is very little out there but the published literature reports on just a handful of cases of patients seriously harmed or dying as a consequence of information gathered online, typically through shunning traditional medical treatment to try alternative medicines. Such information might also come from books, though, or misinformed celebrities. Compare that to how many people die of cars, handguns, or even medical accidents, and you might conclude that, in the grand scheme of things, patients connecting with one another is pretty safe.

We also have to weigh that up against how many lives might have been saved by the Internet. We just don’t know. I believe patients living with disease today desperately need tools to help them manage their health, and be engaged in it. We see that cascade happening at last; consider now in diabetes, patients are today doing themselves what a nurse used to do. Nurses are doing what doctors used to do. Generalist doctors are now doing what specialists would do. So the kinds of tools and the abilities of people have all been upgraded across the board — and that includes patients.

It seems you’re driven by outrage at the injustice of disease in general. Is there a personal hook to this? Is there someone in your family who had ALS or MS?

Fortunately not, but during my training I often used to think, “This could happen to me.” ALS could come out of nowhere and wipe you out. So that gave me a real sense of urgency to cram in as much utility for the rest of the world as I could into a short space of time, because you can’t assume that you’ll get around to it when you retire. As a specialist in the inherited forms of ALS I would also go to people’s homes and play with their kids — some of them had a 50/50 chance of getting ALS when they grew up, and I don’t want them dying of the disease their parents had.

You could have chosen any number of things that save the world. Why neurological diseases?

Your brain is your world. Once I got a taste of the very broad scope and the very personal reach of all this suffering, it was very difficult to ignore. In the days after 9/11, I was a carer for children with learning disabilities, and I read a report in the newspaper of a woman who jumped off a bridge with her son with autism because she thought that in the event of “World War Three” (which felt likely at the time), no one would would be around to care for people like her son. And that really struck me.

Individual contributions are absolutely what’s needed. But even if you have all the nice volunteers in the world, they can’t be effective without a system that is inherently scalable, that could work as well for a billion people as it could for a thousand, so that you can exponentially leverage these volunteers or that knowledge. So I see systems like PatientsLikeMe as being great levelers that any number of people can use. All it takes is people submitting their experience, or their advice, even a smiley face to cheer someone up. It all helps. Building those systems allows the power of the crowd to do its work. I feel incredibly lucky to be one of the architects that do that.

Comments (8)

Pingback: Connecting patients online: Fellows Friday with Paul Wicks | TEDFellows Blog

Pingback: Steve Case takes a road trip, JR turns the Panthéon Inside Out, plus insights into what’s killing bees | BizBox B2B Social Site

Pingback: A listening cure: PatientsLikeMe gives patients voice in clinical trial design | TEDFellows Blog