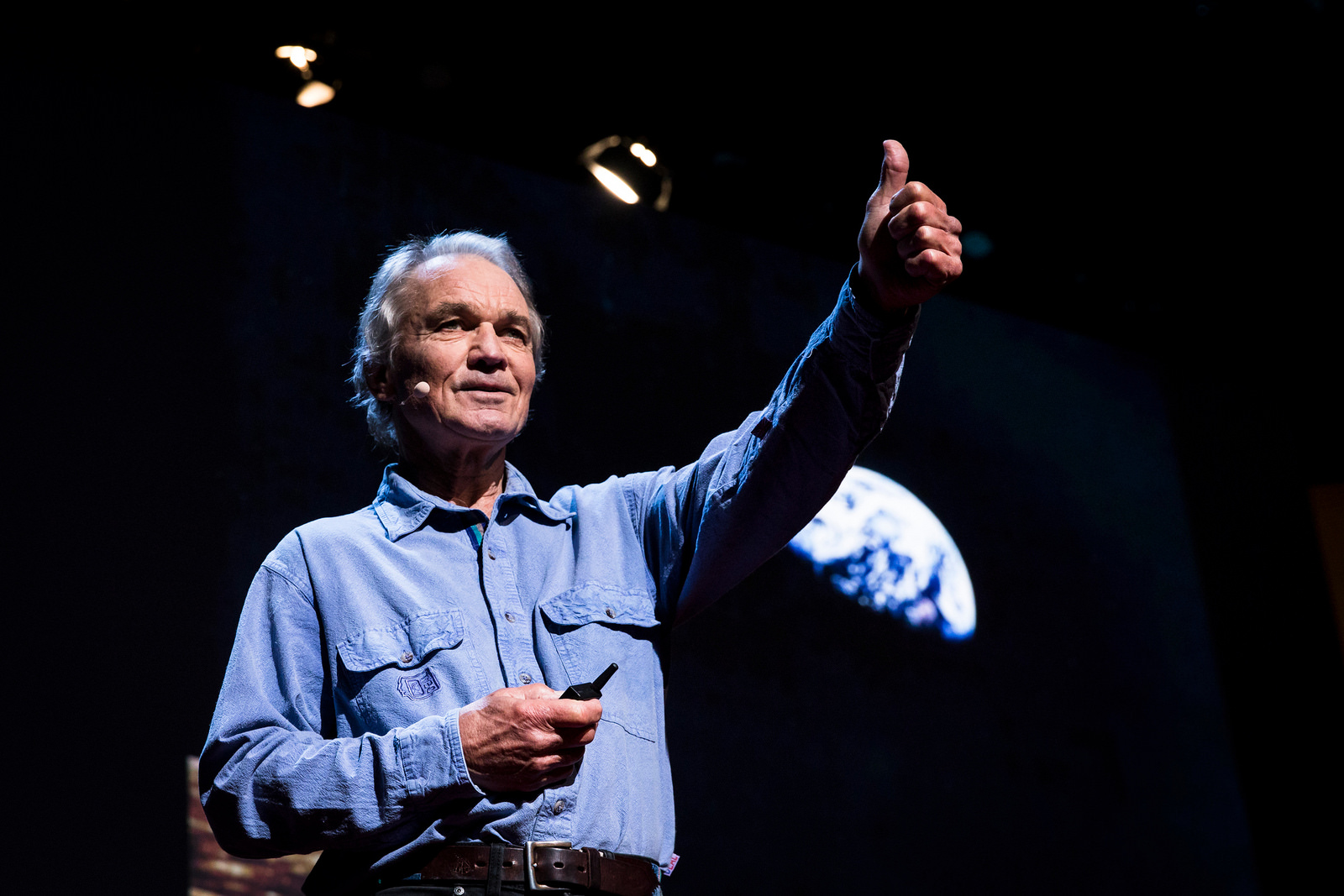

Ian McCallum speaks onstage at TEDWomen 2016. Behind him is an image of the historic photo “Earthrise,” a view of our home planet from space. As astronaut Jim Lovell said: “Everything that you’ve ever known, your loved ones, your business, the problems of the Earth itself … is all behind your thumb.” Photo: Marla Aufmuth / TED

In December 1968, the crew of the Apollo 8 space mission captured a historic photo: “Earthrise,” an image of our home planet as seen from lunar orbit. Astronaut Jim Lovell was on that mission, and here’s what he said: “Everything that you’ve ever known, your loved ones, your business, the problems of the Earth itself … is all behind your thumb.” It was a poetic reflection on the frailty of life contained within that planet, and it echoed the observations of poets past and present that nature exists as an interconnected web of experiences between people and their environments.

Ian McCallum, a poet and psychiatrist, counts himself as just one of many voices who highlight this relationship, suggesting that so much of what makes up the natural world is also shared by living mammals like us.

His message is, in part, one of warning, of human development that’s created devastating effects on elephants, rhinoceroses, forests, and other keystone species vital to the Earth’s ecosystem. In the nearly 50 years since James Lovell and the other members of Apollo 8 gazed at our planet from the shelter of space, Earth has seen its ecological balance become more and more precarious through the actions of poachers and other human agents.

Ironically, while humans create so much environmental change, we are ourselves not a keystone species, McCallum says, not essential to any larger ecosystem. “Were we to disappear tomorrow,” he says, “nothing would miss us.”

But despite the best efforts of scientists to call us humans to account, people still exhibit apathy toward “the ecological warning calls of science.” In the absence of such reactions, he says, “the only voice left that can awaken us belongs to the poets.” Poetry is as much “a language of protest” as it is “a language of hope,” and it pushes us to be bold in how we address problems and ideas. It challenges us to be “keystone individuals” even if we aren’t a keystone species: to be “someone who can make a difference to the lives of others, to the animals, and to the Earth; someone who is willing to be disturbed” and willing “to stand firm in the knowledge that there are some things that are simply not for sale.”

It is, at its core, a process of self-examination, as poetry reminds us to consider what McCallum stresses we seem to have forgotten:

“that wilderness is not a place,

but a pattern of soul

where every tree, every bird and beast

is a soul maker[.]” — Wilderness, Ian McCallum, 1998