When Justin Dowd worked as a food runner at a restaurant, he would sometimes doodle on the chalkboard in the kitchen. He had no idea that this skill — coupled with his ability to explain physics — would one day win him a trip to space.

The science writer and animator who created the TED-Ed lesson “Could comets be the source of life on Earth?” Dowd is known for illuminating concepts in physics — from Einstein’s discovery to black holes — using his own special brand of “chalkimation.” In 2012, his animated videos won him the Race for Space, a competition run by Metro to send a civilian astronaut on a short suborbital flight. Dowd will have a seat on-board the suborbital spaceplane XCOR Lynx and will chronicle his training and the flight for the newspaper.

We caught up with Dowd to talk about science, his upcoming trip to the cosmos and the wonders of creating this TED-Ed lesson out of nothing but chalk.

So, first of all, how did you pick the topic of comets for your TED-Ed lesson?

The lesson is about the discovery of amino acids and DNA-based pairs in the tails of comets, and the discovery that one out of five stars in our galaxy has a planet orbiting in it with a similar size and temperature to Earth. Those are two discoveries that have been made recently — the amino acids discovery was made in 2004, and the Kepler study, which was the study that revealed about 40 million planets that are similar to Earth in our galaxy, came out about six months ago. These are both really, really recent discoveries that are indicating that the building blocks for proteins and DNA are common throughout our galaxy.

The last three years in physics have been the most exciting few years in, I’m guessing, about 20. There’s just been an extremely high density of amazing discoveries that people have been waiting for for decades. So it’s cool to pick these topics that have information in them that nobody has ever known before. That we know for the first time ever.

A still from this lesson, drawn completely in chalk by Justin Dowd.

The lesson looks beautiful. Why were you drawn to chalk as a medium?

I’ve been doing chalk videos for about four years now. The first time I ever drew on a chalkboard was in the kitchen of a restaurant where I was a food runner. The restaurant had a unique chalkboard where it wasn’t slate — it was wallboard with chalkboard paint over it — and it had this texture which allows you to work the chalk with your fingers and get really bright colors out of it.

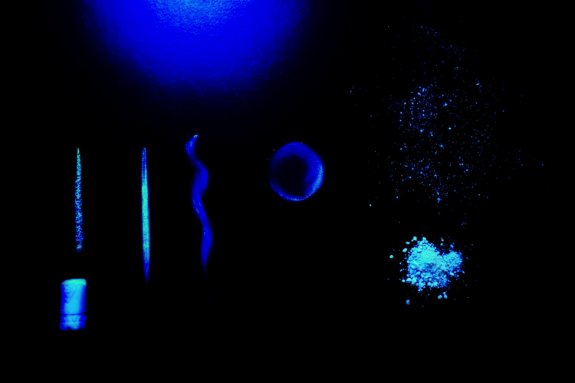

For some reason, chalk and I get along. It’s kind of like a finger painting that’s dry because every color and every chalk stroke is gone over with your hands. You can dip your fingers in the powder and use your hands as a brush. And you can also erase it with your hands and move an image around. So when you’re doing animation, instead of doing multiple pictures that are separate, you can draw one mural and just manipulate the mural so that the images on it are slowly moving. You take pictures as you go, and once you have around 1,000 pictures, you have a minute or two of animation. It’s kind of gritty, and I get a lot of depth in the images.

A peek into Dowd’s method. From left to right: A drawn line of chalk, two lines of chalk shaded with a finger, a circle of chalk shaded with a finger, and chalk ground into powder for stars. Photo: Justin Dowd

Are there any challenges to keep in mind when working with chalk?

I tried to take this lesson up a notch from what I’ve done in the past. I wanted to go all-out. So I tried a lot of new, experimental techniques, and developing those was the hardest part. Pretty much everything that I’ve done in animation, the first idea looks good on paper, but then when you try and do it, it doesn’t work out. Some of the best things that I’ve learned how to do with chalk have been accidents.

For example, the stars that I use in the space images are chalk ground up into powder. You just pick up a little bit of chalk, snap your fingers, and tiny specks of it fall down on a chalkboard that’s laid horizontally, and it looks just like stars. The first time that I noticed that was when I was drawing on the chalkboard. I looked down at all these little specks, and it looked just like stars — and that’s something that I’d been trying to figure out. I’ve been using that technique ever since.

A look at Dowd’s home animation set-up. Photo: Justin Dowd

Speaking of space … you’re going to visit it soon. How did you hear about this contest?

I heard about it while I was doing a Sudoku on the T in Boston. They had an article about it in the Metro newspaper. I decided to enter, and to do something different, I decided to make animated videos using chalkboards explaining the basics of relativity. I didn’t expect to win. It was really a shot in the dark, but I’m extremely lucky to have been able to get a trip to space in the end.

The trip will be in about a year from now. They’re finishing the rocket in the Mojave Desert. I can’t wait. I would fly tomorrow morning, if I could.

How long will you be in space?

It’s a short trip. It’s kind of like being shot out of a cannon, straight up. It takes four minutes to get about 65-70 miles up. It goes three times the speed of sound, and we float for about 15 minutes, and then re-enter the atmosphere, and the rocket becomes a glider and glides back and lands on a runway like a plane. It’ll take about an hour and a half. Most of it is gliding back down.

That’s going to be amazing. Any last thoughts you want to leave us with about your TED-Ed lesson?

My favorite fact in the lesson is the discovery that there are 40 million planets similar to Earth that likely have DNA base-pairs, and the building blocks of proteins are planted in all of them by comets. I’ll see shows on science channels where it’s like, “Comets: Apocalypse Doomsday” — all different things that make the solar system and galaxy seem hostile. But the more that we study the universe and the galaxy, the more these things like comets — which appear to be hostile — are actually factories for creating the raw materials of life. The laws of the universe give us little pockets of safety, and outside of these pockets, in space, are actually the perfect conditions to create the building blocks of life.

A still from the final animation of this lesson. Could comets be more than meets the eye?

This post originally ran on the TED-Ed Blog, where you can learn much more about our education initiative which uses animation to spark curiosity. Read more from the TED-Ed Blog:

Comments (1)