How did human emotions evolve to help us survive? For the last decade, cultural anthropologist Chelsea Shields Strayer has studied the indigenous healing practices of the Ashante people of Ghana, discovering that emotional pain serves useful purposes — including the relief of physical pain. In this conversation with the TED Blog, she tells the fascinating story of how she struggled to free herself from her gender-biased Mormon culture to study another culture far away, in the process gathering important information about the physiological basis of the placebo effect, learning how social ostracization affects physical well-being, and getting a new perspective on the community she comes from.

How did you end up studying traditional healing cultures in Ghana?

I grew up in a very conservative Mormon culture in Utah. My father works for the church educational system, and my mother is a stay-at-home mom of eight. None of the women in my family have ever gotten a higher education or worked outside the home, so I didn’t have any role models outside my own culture, or any within it of women pursuing less traditional paths. I was a four-sport athlete and had straight As during high school, but it never even crossed my mind that I could go anywhere besides the church university, where traditional gender roles were reinforced every day. My female pre-med friends were told that if they got into medical school they would be “taking the spot of a man that needed to provide for his family.” I never even had a female professor until my senior year.

Because of the rigid modesty culture that makes you a “good Mormon girl” I had never even kissed anyone until college. At 19, I started to date my first boyfriend. Everyone, including my church leaders, wanted me to marry him. There was a lot of pressure. So I remember feeling really trapped and very confused. I believed in my religious leaders; I believed they received revelation from God. But I did not want to marry; I was so young, and had so many things I wanted to do.

So I very quixotically said, “I can’t do anything until I accomplish my goal — which is go to Africa someday.” My boyfriend said, “Okay, I guess we could do that later, when we’re married. We can go as missionaries.” Again, so much pressure not to do my thing. I was almost like a drowning person. I just had to do something, to get out. So eventually I just did it. I bought a plane ticket to West Africa. I left the country for the first time, at 20 years old, all by myself.

What did your parents think?

No one had ever been to Africa, so they didn’t know anything. We were all just super naive. I don’t think they realized how scary it was. I don’t think even I realized. I remember my dad taking me to San Francisco International Airport and it hit me. This silly plan of mine was actually coming to fruition! I had no idea what would be on the other side of the world when I stepped off the plane. It was terrifying. The best moment, however, was when my mom called me and with tears in her voice said she was really proud of me — proud that I had a dream and that I was making it happen. How rare and special that was. I think that is what gave me the strength to get on the plane and not just live in SFO airport for six months, which was my Plan B.

I attended the University of Ghana in Legon for a semester as an international student and lived in the dorms with Ghanaian roommates. I made a lot of friends, attended my local Mormon ward in Ghana and spent the entire time immersing myself in the culture, backpacking and traveling throughout West Africa.

Being in a completely different culture was good for me, but it was really hard. I didn’t speak the language. I didn’t understand the social norms. I would see Ghanaian street vendors selling things on their head and I didn’t know what was food or soap (I only made that mistake once)! It took a good four or five months of being completely out of my comfort zone and changing everything about my life (what I ate, where I slept, how I went to the bathroom, how I showered, what I wore, how I communicated, how I spent my time, etc) until resilience kicked in and I adjusted to this new lifestyle.

You see, in my culture women are supposed to be very beautiful and high-maintenance because your job is to look attractive so you can get married someday. And here I was sitting in this country where my makeup is melting off in the 100% humidity, my nice clothes are dirty in two seconds via the dirt paths and crowded tro-tros, my padded bras are completely uncomfortable in the two 12-mile walks you take every day to get anywhere, and I was blow-drying my hair (when there was electricity) while sweating so much it would re-wet my hair. Very quickly, I had to get rid of all those cultural symbols I had about who I was and what made me special. I was stripped of everything I knew, and it forced me to create a new worldview where my decisions were based a little less on what I was “supposed” to do and a little more on what I “wanted” to do.

A long way from home: Shields Strayer dances with a healer as he prepares to go into spirit possession.

How did you get involved with the healing community in Ghana?

When I got back to Utah, I had enough perspective and strength to start making decisions about what I wanted. I broke up with my boyfriend, said I didn’t want to get married before I got a degree, decided to major in anthropology and helped start a study-abroad program to Ghana at my university. I ran that program in different capacities for about five years while I finished school.

All along the way, I had to fight and push against invisible patriarchal boundaries that exist in my culture. Even though I was a top anthropology student, it surprised faculty, family and friends when I applied to graduate school, but I received a Foreign Language and Area (FLAS) full-ride scholarship to Boston University for an MA/PhD in anthropology and African studies.

Over the course of the last twelve years I went back to Ghana five times, for a total of 26 months. I became friends with some Asante healers early on, and have maintained those relationships over the last decade. I’ve watched them go from apprentices to master healers, I’ve been invited to attend everything from very private ceremonies to public performances for the Asantehene King, I have even had healers who allow me to record and take measurements of them in spirit possession.

Was your interest in anthropology always focused on healing culture?

Not at first. My BA, MA and PhD were in cultural anthropology, and I was studying the religious and social aspects of Asante indigenous healing. At first, I was more concerned with what all of the cultural symbols in ritual healing meant, rather than how it worked. Halfway through my research, though, I realized that my informants and I were talking past each other. They would tell me about witchcraft cursings, familial discord and the process through which they cured a patient, and I would build an ethnomedical explanatory model — which explained Asante sociocultural constructions of sickness and healing. They were talking about ritual healing ceremonies as effective techniques for altering physiological pathologies, and I was describing why they thought that. I was not discovering if ritual ceremonies actually alter physiological processes or how and why they do it. I did not have the tools to understand, frame or measure those claims. So I went back to Boston University and completed all of the PhD requirements in biological anthropology as well.

Why did you need to study biological anthropology?

The healers I’ve worked with don’t think that they are just building the community, easing tensions or creating social support. They say they are healing — affecting a physiological change. I felt that no matter how I wrote about what they were doing, from my academic perspective, I was belittling their biophysiological claims of ritual healing unless I could understand and explain why and how social processes can influence physiological ones.

What I learned from the healers was that because the body is made up of both spiritual and physical matter, variables affected in one state can manifest in the other. Since non-physical or psycho-social (social, psychological, spiritual, etc.) variables can influence bodily states, the healer’s job is to manipulate those psychosocial processes in order to elicit specific reactions from the body. This is not a foreign concept in mind-body medicine. We know that psychosocial factors such as stress, fear, inferiority, ostracism and negative expectations exacerbate physical and mental ailments and inhibit healing processes. We also know that relaxation, expectations, empathetic relationships and meaningful interventions can activate and even enhance healing processes. What we are talking about are the context-specific physiological effects of the ritual of medicine, the provisions of care. Another word for this phenomenon is the “placebo effect.”

There’s a lot of confusion around the placebo effect. How do you approach it?

Having studied it for the last eight years I can tell you that most people don’t really understand what it is. The most common understanding is that a placebo effect means that nothing is happening when the opposite is actually the case. Something biochemically is happening — it is just that the cause is psychosocial rather than physical. An inert sugar pill has no physical effect on the body, but that same pill — when wrapped in all of the rituals, meanings and social interactions of healthcare and imbued with encultured expectations — has incredible and powerful effects of the body! A handful of anthropologists have been talking about this for years, the effect that meaning has on the healing process. What I contribute to this dialogue is describing the effect that social interaction has on the healing process. I meticulously go back through our evolutionary history and show how encephalization and increased sociality, infant dependency, juvenility and attachment make human bodies particularly vulnerable to changes in our psychosocial environments. I show how for our ancestors, belonging and ostracism literally made the difference between life and death and how we evolved very powerful prosocial emotions (psychological and physiological warning systems) that are hypersensitive to cues in our social environments. Because the fitness consequences of prosocial behavior was so costly to our ancestors, our bodies are full of somatic “warning” systems that keep us from being too anti-social.

For example, one of these warning systems is social pain, or the unpleasant sensory experience we feel when we make a social misstep; that moment of cringing or embarrassment when we’ve put our foot in our mouth or the anxiety-riddled feeling right before a speech, interview or performance. Like many of our adaptations, the social pain warning system evolved out of and on top of preexisting structures in our bodies — in this case our physical pain warning system. This is called the pain overlap theory, and basically states that because these two warning systems occupy the same neural pathways, you can inhibit the one by activating the other.

The best examples of this are when someone self harms or cuts themselves in order to numb the psychosocial pain they are experiencing or, on the opposite side of the coin, when someone’s social environment determines how much physical pain they experience. (Think about a skateboarder having a horribly painful fall but getting up quickly and laughing it off because he doesn’t want to lose status in front of his friends, or a baby who falls and then looks up to her mother to determine whether she should cry or not.)

A bone setter massages a boy’s broken arm with an herbal lotion. In the final photo you can see the boy’s pain and the healer’s laughter; trying to normalize and minimize the pain. Photo: Chelsea Shields Strayer

How does what you observed with Asante healers fit into this?

The most fascinating aspect of all this for me is discovering the culturally specific techniques that Asante healers use to mediate all of these evolved endogenous processes. One of the most poignant case studies was a 9-year-old boy who broke his arm and was at a consultation with a local bone setter. The bone setter unwrapped his sling, checked that the arm was set properly and then rubbed the arm with ointments and an herbal poultice. As you can imagine, this was an extremely painful process and at the beginning — before the bone setter had even unwrapped the sling, the boy cringed and shifted his body away, naturally anticipating pain. Instead of comforting and calming the patient down as we might expect, the bone setter smacked the boy upside his head and laughed really loud. Then he called all of the other patients and healers to come closer so they can see a silly boy who was afraid. The bone setter continued to humiliate the boy by explaining how so many of his other patients — who were younger, weaker and frailer — had no problems sitting still. The surrounding crowd laughed, the boy blushed with embarrassment, handed his arm over to the bone setter and maintained a stoic expression throughout the rest of the treatment process.

Now, I am not suggesting that healthcare practitioners should start smacking, yelling or belittling patients. But in a land where pain medication is not available, Asante healers have devised powerful behavior-based analgesic techniques. Smacking the boy activated and/or increased the stress response, which elicited a powerful cocktail of pain-reducing hormones, including adrenaline and endorphins. The bone setter then distracted the boy from his pain by teasing him and forcing him to focus on all of the people around him. He normalized and even lessened the pain by laughing and bringing up other weaker patients, thereby, altering this boy’s expectations (one of the most powerful placebo triggers). The bone setter also numbed pain by threatening the boy’s status and making him anxious and embarrassed about his social position which triggers a social pain response and physically co-opts acute pain. Finally, the bone setter expressed his own dominance and competence, which allowed the young man to trust him and experience all of the endogenous healing mechanisms of interpersonal neurobiology and the therapeutic relationship.

The first time I witnessed an Asante healer’s reaction to a patient’s pain I was flabbergasted and horrified. Why would anyone see another person suffering and tease them? It was only after hundreds of field experiences and going back to understand the evolutionary biology of social interactions that I began to realize that these behaviors actually alleviate suffering — that there are hundreds of behaviors that alleviate suffering.

How might this knowledge be applied in the Western world?

We could, for example, come up with psychosocial techniques to minimize pain in the absence of medication, when someone is injured in a remote area. Our bodies evolved in environments where psychosocial behaviors — rather than biomedical techniques and medications — were used to mediate sickness, healing, pain and distress, and we are highly susceptible to psychosocial manipulation. If we don’t understand how our bodies evolved we are, at best, neglecting and often interrupting and/or impeding endogenous healing mechanisms and, at worst, exacerbating, intensifying and even triggering prolonged suffering. After the last two decades of placebo studies research, is not enough anymore for healthcare practitioners to be aware of how pharmaceuticals interact with the body — they also need to understand how social reactions influence the body, for better or worse.

In a talk you gave at the TED Fellows retreat, you discussed the ways we interact with social circles in our own culture, and how our emotions affect our physical well-being. Should we be avoiding heartbreak?

Not at all. It’s more like when we have a fever. Our body heats up in order to kill bacteria, and our response nowadays is to reduce the fever, because we don’t like to feel uncomfortable. Right? But if we look at it from an evolutionary perspective, the fever’s there for a reason. Your body naturally selected that adaptation because people whose bodies could heat up and kill off pathogens survived and reproduced at higher rates than those who were “comfortable.”

That’s how I want us to start looking at heartbreak and depression and anxiety. You feel anxiety because something in your social domain is making you feel that you don’t fully belong, or that you are not socially embedded enough. It’s an indicator of something in your social domain that’s not right. We are conditioned to think painful emotions and responses are bad, have no purpose, and our first reaction is to alleviate them as quickly as possible. I think we should look at them from an evolutionary perspective, as an indicator that points to how improvements could be made. What is my anxiety telling me? Or, why do we feel grief or heartbreak? Yes, it’s horrible to experience, but the reason it’s so potent and powerful is to signal to us. For example, the urge to withdraw completely following heartbreak, often seen as antisocial behavior, actually serves a prosocial purpose: to have time to ruminate, to figure out what went wrong, how to do better next time, take space to calm yourself, and even how to learn to invest in people who are less likely to cheat and lie and more willing to help and sacrifice for us. All our emotions are actually adaptive traits that helped us to function better in our social domains.

Difficult emotions related to social rejection might be based on real circumstances, such as being bullied at school, but might it also just be neurosis? What if you feel anxious that you don’t belong — even though you do? How would you address that?

One of the problems is all of these adaptations evolved in a social environment that was quite different from how we live now. In a family-based lineage group, you have some cohorts your age, but not 500 in a high school, right? There were smaller groups, they were family — so those triggers probably would not have been stimulated as often. How many heartbreaks in a small lineage-based hunter-gatherer group is someone going to experience? In your own family group, how many rejection moments? Enough to mediate your behavior toward pro-sociality, but not enough to cause persistent anxiety or neurosis.

The problem is that nowadays, our far more complex social settings — workplaces, high school, Facebook — are triggering these mechanisms so often, so intensely and for such prolonged periods that it’s making us sick. Our large brains are fantastic! They facilitated our ability to adapt across the entire spectrum of climates and ecologies on earth (and space!) and led to unbelievable technological advancements. But they also demanded hyper-attachment and dependency on other people to survive and are the byproduct of an exponentially increasing social group. Our prosocial emotions are no longer being activated a few times in a kin-based organization. They are consistently being threatened in social networks, technology and industry, and our bodies are not used to withstanding that many constant and competing social signals.

So with Facebook, you make yourself vulnerable to being judged constantly, so the rate of being rejected can be much, much higher?

Yes.

What do we do about that? Physiologically, we can’t help but be triggered by the possibility of social rejection, but the human need and desire to connect is incredibly strong, which is why we do this. How do we bridge the gap? We need curanderos!

Yeah, we do! We do. That’s one of the things I love about ritual healing, is it’s not just a doctor and patient, it’s a community. The ritual really does make someone feel more connected to their community, and there’s many steps in ritual healing that allow someone to get over these feelings of rejection and ostracism.

I think we first need to start talking about these feelings of rejection, bullying and ostracism as real things. Not just “It’s in your head.” There’s a reason people kill themselves. There’s a reason why being ostracized is so bad for your health. If we take them more seriously, then it’s okay to feel bad when you’re rejected. Belonging used to be a matter of life and death. That is a big deal. You are supposed to feel bad if you are rejected. Your body was made that way. The question is, what are you going to learn from that unpleasant feeling that will help you next time around?

Do you see any mechanisms now that are evolving along with our ability to connect at such at an intense rate, and conversely reject each other with equal intensity? Are we adapting now, in some ways?

Interesting. Well, social and cultural adaptations evolve at such a faster rate than biological ones. Clearly our biological bodies are still in the Pleistocene with our family groups. And our technology has resulted in these crazy socially networked lives. We’re constantly creating things. Every day there’s a new app. Every day there’s a new thing to help us relax, to help us feel more part of a group. We’re always creating informal networks. If someone doesn’t like me in that group, I’m going to unfriend them and join another one. We’re always doing things to feel like we belong. And there’s some groups that we really belong to, some groups we’re involved with peripherally. We’re constantly trying to create these communities and negotiate between them. My educated guess is that we are adapting coping mechanisms and techniques that help us withstand the intensity of modern social life. Those of us with that resilience will survive and reproduce at higher rates than those without it and we could potentially see some genotypic markers down the road. In fact, we already know that our bodies respond at an epigenetic level to early childhood stress, particularly in the social domain, that have lasting effects on our genome for the rest of our lives and can even be passed on to our children. So these are important questions!

I think one problem with online communities is that they are quite different from physical communities. So sometimes we’ll invest in these online relationships, but then when we need physical support, it’s not there. So we can’t let our virtual relationships co-opt some of the more physical relationships that we need.

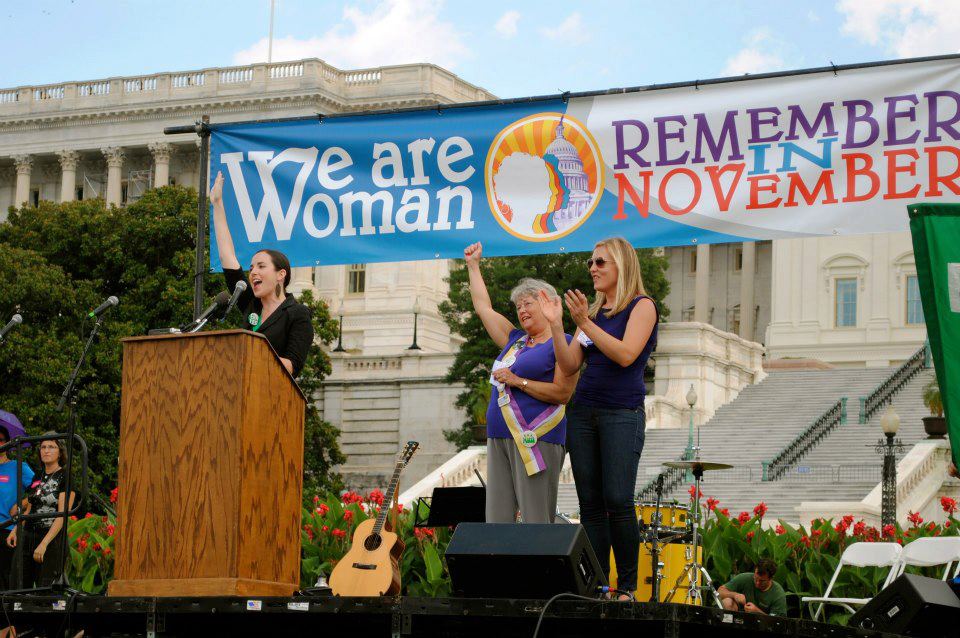

Speaking at the We are Woman march at the US Capitol in Washington, DC November for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

So what about you? Circling back to your upbringing, how have you reconciled your life now and understanding of the world with your family?

I was raised in this culture where I was taught that “This is the only way to live,” and being an anthropologist, you learn there are a million ways to live. So I think I felt a little bit of betrayal, almost. That the foundation upon which I had built my whole life was gone. And it just felt like all these things I believed in aren’t there. So that’s been hard. That’s been a 10-year journey for me. The other problem is that every time I express doubt or difference of opinion with my culture, I am further ostracized. It is a real lesson in my personal life about the effect of belonging to a group and the pain and suffering of being rejected from one, especially your primary social group.

But I think the good thing is, as an anthropologist, I spend my days watching spirit possessions and witch doctor healings — things that, when I first went, I was like, this is crazy! And that’s my whole job, to stop saying “This is crazy, or bizarre,” and to figure out “Why do people do this? What does it mean? How is this experienced by the person who’s the witch? Or the person who’s the doctor? What are the real consequences of these beliefs?” Having that open mind for other people has allowed me to do the same for my own.

That is not to suggest that I am sitting idly by. I spend many hours a month working as an advocate for religious gender equality. I have become a well-known Mormon feminist activist in interfaith communities, including the national ERA taskforce and Mormons for ERA, and I spoke at the We Are Women Rally on the Capitol in Washington, DC. I am a cofounder and board member of LDS WAVE, a religious advocacy group, and I produce articles, blogs and podcasts regularly. For our actions, many of us have faced serious consequences. I was let go from my adjunct job at a church institution, and told I could not even be considered for a tenure track position. Many women face disciplinary reproach from local leaders and social ostracism from their communities. It hasn’t been easy.

Why are you so passionate about the issue of gender equality in religion? Why not simply live and let live?

Religions are some of the last institutions on the face of the Earth where overt gender discrimination is enforced and acceptable. Much like the actions that forced religious institutions to change their views on God and race 100 years ago, the next fifty years will see enormous changes in how we envision God and women. Most people do not understand the radical nature of this perspective. Most of the 7 billion people on the planet are religious. Religion connects people across national boundaries and asserts more political, economic and human capital than any single country on the earth. From Christianity to Islam, increasing women’s decision making power and authority is the single most important and critical action for women’s rights we can participate in. The possibilities for progress are unparalleled by anything we have seen in this century. But the work is just beginning, and I am on the front line.

And I don’t think I’m at the end of my own personal religious struggle yet. There are still clashes — every day there’s a clash between what I’ve been encultured to believe I am “supposed” to be and who I am. But I think it’s better for all of us to be confronted with a plurality of beliefs and cultures than to just decide, “You are crazy, I’m gone.” Or “You’re different, you should leave.” I think that that type of rejection makes both parties feel horrible. And I think the solution to all of this — if we can combine both stories about my research and my religion — is that social relationships and groups matter. They matter a whole lot. Maybe we should find a way to be more inclusive, respectful, and understanding that people are going to be and think differently, and that is okay.

Comments (9)

Pingback: 057: Mental Health Benefits & Risks of Religion - Part 1 | Mormon Mental Health Podcast

Pingback: Episode 12: Finding Your Tribe With Chelsea - Woman Evolving

Pingback: Come, Come, Ye Saints: Processing and Perspective of Current Events – faith again

Pingback: The Weekend ~ 11/29/13~ Preparation | DCTdesigns Creative Canvas

Pingback: Why belonging matters: Fellows Friday with Chelsea Shields-Strayer | TEDFellows Blog