Candy asks:

If you could ask one question to all of your neighbors, what would you ask?

Click here to respond on Facebook now! Or join Candy’s live Q&A on TED Conversations, Monday, August 1, 3pm-4:30pm Eastern, at http://on.ted.com/ChangQA.

You have so many public art projects going on. What are you working on right now?

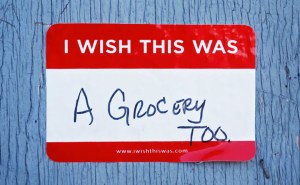

Well, my Civic Center colleagues and I just launched Neighborland. It’s a tool to help residents shape future businesses and services in their neighborhoods. It developed from a public art project I did called “ I Wish This Was,” which was inspired by vacant storefronts. Everybody passes by vacant storefronts and has ideas for what they’d like in them. My neighborhood in New Orleans, for example, doesn’t have a full-service grocery store. What if we actually had some power to influence the kinds of businesses that enter our neighborhood?

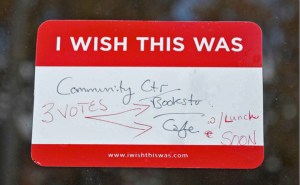

I created fill-in-the-blank stickers that say “I Wish This Was _____” and posted them on vacant storefronts. People wrote things like “a butcher shop,” “a community garden,” and “a taco stand.” It was kind of a lovechild between urban planning and street art. But there’s only so much you can do on a sticker. Some people wrote on each other’s stickers with things like “me too” and “3 votes for that.”

Some of these conversations needed to move to a more constructive space. So we developed the website Neighborland. It will hopefully connect residents who want things with likeminded people, initiatives, and resources. It’s a valuable poll for civic leaders and developers to assess what residents want in different areas. And it promotes entrepreneurship by revealing neighborhood demands and proving there’s a viable customer base for new businesses to open.

As a complement to Neighborland, we’re also developing a public art project called How to Start a Business. Starting a business can be an intimidating process. I’ve done it, and I’ve been totally confused. How do you push people to the next step? How do you make starting a business easier? We’d like to clarify the process and present the information directly on vacant storefronts in New Orleans. We’re still figuring out the details –maybe giant posters will cover the entire storefront — but we’ll also illustrate the process online and invite people to share their experiences. Hopefully this will help more of us turn our dreams into a reality, and tap the entrepreneurial power of New Orleans.

Where do your projects come from?

I think my background in street art, design, and urban planning have shaped a lot of what I like to do. I’m passionate about redefining the ways we use public space to share information that can help improve our neighborhoods. And I’m more and more interested in ways we can share information in public space to improve our personal well-being, too. Thanks to the Alaska Design Forum, I recently made a public art project in Alaska called Looking for Love Again.

I turned a vacant high-rise in Fairbanks into an emotional beacon pleading for love, and inviting people to write on chalkboards at the base of the building. One chalkboard was pragmatic, asking people what hopes they have for the space. And the other chalkboard was more emotional, asking people what memories they have with the building. People shared really touching stories. It became a wonderful glimpse into the history of the area and the emotional impact a building can have on our lives.

Thanks to Flux Aura and the Artist as Neighbor program, I just created a project called Career Path in Turku, Finland. I used temporary spray-chalk to stencil a university path with fill-in-the-blank spaces that say “When I was little I wanted to be ______. Today I want to be ______.” People can use chalk to write directly on the pavement and think about their larger life choices, and also learn about the lives and goals of the people around them. It’s about comparing yourself today to when you were young and thinking about the desires you had as a child when money was no object. Some of my favorite responses are “When I was little I wanted to be a princess. Today I want to be an electrician.” “When I was little I wanted to be a bird. Today I want to be a speech therapist.” “When I was little I wanted to be a grown-up. Today I want to be a kid.”

I’m also working on expanding my Before I Die project. A few months ago, I painted the side of an abandoned house in my neighborhood in New Orleans with chalkboard paint and stenciled it with a grid of the sentence, “Before I die I want to ______.” It’s about remembering what’s important to you and learning about the hopes and aspirations of your neighbors.

I’ve been blown away by the responses on the wall, and the response to the project. I’ve received hundreds of requests from people around the world who’d like to make a Before I Die wall in their city. So we’re working on creating a kit with a one-column stencil and a how-to guide to make it easier for people to reproduce the wall in their community. We’re also working on limited-edition paintings, a book, and more installations. I just made mini Before I Die walls with students in Kazakhstan, and the next place my Civic Center colleagues and I will be installing is out West in the desert of America later this year.

Don’t you have problems with people abusing the space you open up for comments?

Yeah, that’s the most common pushback I get on these projects when I try to get permission from community groups. They’re often afraid that it might draw lewd comments. I always assure them I’ll monitor it every day. We do get some inappropriate comments, but really much fewer than anybody expects. To me, it’s worth a few penis doodles if that means there’s that much more constructive input from the community. All of these projects are experiments, full of unknowns. But it’s a shame if the fear of graffiti trumps the desire for more constructive community input.

Though a lot of your pieces have technological components, you’ve said you really value a strong analogue base. Why?

I started using analogue tools because it was what I could do, as one person, with the skills I had. And then I realized there’s another benefit to low-tech projects that I didn’t even think about at first: it is so accessible to everybody. There’s no barrier to entry. I don’t think you would have seen all these responses to I Wish This Was, Career Path, Before I Die, or Looking for Love Again if the platforms were only online. And what happens to all those voices that never make it online?

When you say, “This is what the community wants” it’s usually the four or five loudest people, or the 10 people who can make it to the community meeting. So how do you make the discussion more reflective of what the community actually wants? A low-tech format makes it easy for all residents to chime in.

What has inspired you to make the leap from your corporate job in Finland to doing experimental public art full-time in New Orleans?

I’d worked here in New Orleans the summer of 2006 on a criminal justice project, Million Dollar Blocks. Like so many other people, I fell in love with the city, and thought that I’d like to live here some day.

I was living in Helsinki last year, working for Nokia as a design researcher. Within the course of a few months a lot of personal tragedy happened to me and a few of my friends. One of my friends lost his father. Another friend lost his young son. I lost someone who was like my second mother. It made me really aware that life is brief and tender and not to be delayed. It made me think hard about what I really wanted to do in my life, about what was really important to me. This was part of the inspiration for the Before I Die project.

I loved working with these people in Finland, and they taught me so much. But I realized my heart was in public space, and experimenting in different ways to make cities better. So that’s when I decided to move to New Orleans to work in public art full-time.

I think I’m hooked on palm trees now. That was actually one of my childhood dreams: to live somewhere with palm trees. And now I’m finally doing it.

There are many aspiring social entrepreneurs out there who are trying to take their passion and ideas to the next level. What is one piece of advice you would give to them based on your own experiences and successes? Learn more about how to become a great social entrepreneur from all of the TED Fellows on the Case Foundation’s Social Citizens blog.

Write the bio that you want, and keep checking on it. On my website, one of the pages I edit the most is my bio page. That’s really for myself. I think it’s a good exercise to write about yourself: your accomplishments, your aspirations, and what is really important to you. I think it’s a great foundation to work off of and continue to tinker with over the years.

I think most of the things that I’ve done for the last five years have come from taking advantage of unexpected opportunities. My written bio helps confirm or challenge these moves, the things I’m doing, or thinking of doing. It keeps me thinking about how I’m spending my short time in the world, and if it’s fulfilling.

How was your TEDGlobal 2011 experience as a Senior Fellow?

TEDGlobal 2011 was intense and inspiring and I will simmer on a lot of ideas churned up from the event for a long time. It’s also become a lovely reunion with the TED Senior Fellows and an exciting romp with the new fellows. I’m so grateful to be a part of the TED Fellows family. It gets bigger, brighter, and bad-asser every time. And I’ve definitely made friends for life. It’s not just because the Fellows are all doing amazing things. It’s also because of their attitude. We bounce ideas off each other, but we also get our dance on!

I think it’s great to be connected to people who are doing very different things from you. I think it’s quite easy to bury yourself in a niche discipline. Just being in closer touch with them is a good reminder of how often we can overlap. Because of all the tweets, Facebook posts and blogs, they’re part of my daily headspace. And there’s a lot of inspiration there.

Besides the TED Fellows, what other interdisciplinary thinkers have inspired your work?

I’m mesmerized by people like Joseph Paxton. He was a gardener in the 1800s and he was the first person in England to grow the giant water lily plant. It grows to something like six feet in diameter. It has a special cross-ribbed structure that gives it a rigid form, and this made Joseph wonder how strong it really was. So he put his kid on it! He put his kid on a lily pad … and it still floated. And he didn’t stop there. He somehow found other people’s children and put them on the lily pad, too. He found out it could support a whopping five or six kids, and that made him wonder if the structure could be applied to other things. So he used the same pattern to make experimental greenhouses. And then he made the Crystal Palace, this gigantic cast iron and glass building in London for the Great Exhibition of 1851.

So he translated the ribbing structure of the giant water lily plant to an enormous building. And I love this story because it’s inspiring to see how open-minded he was, to think, “Hey, that leaf would make a great building.” I really like that a gardener can be an architect. Which makes me think about the idea of disciplines. I think we can make disciplines as big or as small as we like. There are lots of spaces between traditional disciplines and no one says you can’t go outside the lines. So it seems only natural that we each make our own discipline out of the bits and pieces that we’re interested in.

Comments (9)

Pingback: TED Blog | Fellows Friday with Candy Chang | TKH Realty is Denver Real Estate

Pingback: Before I die I want to... (video)

Pingback: Making participation the experience, and vice-versa. | Curious Fridays

Pingback: 6 art installations by Candy Chang that make the viewer part of the piece | Krantenkoppen Tech

Pingback: Urban Art Around the World: The Best YOLO Project Ever | Designed Good

Pingback: Recognizing, understanding and improving upon the creative process inherent in family processes. « artismm

Pingback: the wall again «

Pingback: TED Blog | Fellows Friday with Candy Chang « Your Real Estate Adventure

Pingback: Using architecture to bring out the unseen |