Interactive Fellows Friday Feature:

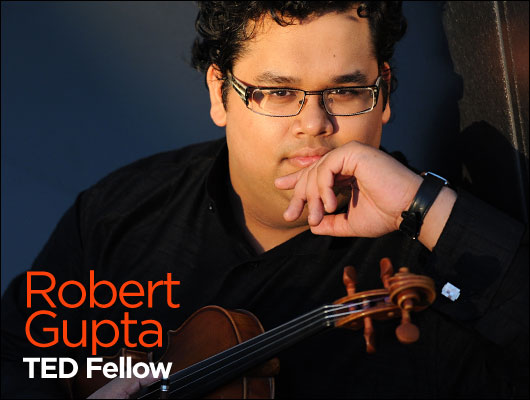

Join the conversation by answering Fellows’ weekly questions via Facebook. This week, Robert asks:

With the advent of amazing online videos, why are we still so compelled to experience live performance (music, sports games, dance)?

Starting Saturday, click here to respond!

As a TED Senior Fellow, you got to attend TEDGlobal 2011. How was your first TEDGlobal experience?

It was unbelievable. I’ve been to two previous TEDs in Long Beach, but TEDGlobal was a very different experience: us Fellows had some more time to bond, which was great. The entering class of Fellows at TED Global 2011 was ridiculously awesome. I always walk away from TED feeling like, “Wow, I’m doing nothing. I have to do more.” Seeing the other Fellows always give me such inspiration.

It’s amazing to track how I am personally developing through TED Conferences. Part of being a Fellow means receiving validation for my crazy ideas. The rest of the world may think I’m nuts, but the TED team thinks I should be nurturing those ideas and building on them.

Tell us about some of those “crazy ideas” that TED inspired you to follow up on. What’s next on your plate?

I’m starting a non-profit organization called Street Symphony that brings live music to the homeless and mentally ill on Skid Row. The mission statement of the non-profit is to bring music to the most underserved communities throughout L.A. I also want to play for autistic children, veterans, victims of massive brain trauma, prisoners, at hospices, on Indian reservations ….

At my first TED, I spoke about my experience with Nathaniel Ayers, a paranoid schizophrenic musician. Seeing all the things other Fellows and TEDsters were doing, it wasn’t enough anymore to have just had this experience with Nathaniel. I desperately wanted to come back to TED, and to expand my work I’d begun with Nathaniel. So when I came back to TED as a Senior Fellow, Adrian Hong, one of the other Senior Fellows, said, “If you want to do something, you should start a non-profit.” And we sat down and did a budget right there at TED. Now he’s on my board.

In terms of career paths, I’m extremely happy where I am right now. Playing with the LA Philharmonic is a dream job. Our new director, Gustavo Dudamel, is a genius, and it is amazing to make music with him. And we play at Disney Hall, and I have a chance to live in LA, and there is all this amazing music happening here.

You recently recorded your Kickstarter-funded debut album, which includes your original Indian Raga, European classical music, and American music composed for you. When will the album be released?

We still have to do editing, mastering, producing, and pressing. We’re aiming for the beginning of next year for the release.

Recording the album was an incredible experience. We were able to record at Disney Hall, and I had the chance to play on an amazing violin: the 1716 Milstein Stradivarius. For me, to even be in the same room as that instrument makes me act like a puppy on Ritalin. I just go nuts.

I could have done something more conventional, but I really wanted to say something personal with my debut album. I always swore to myself that I would learn to play Indian classical music, and I had never done that before. So between Wikipedia and iTunes and YouTube, I taught myself how to write a raga. The journey of the recording is from that raga, going to LA, where we play music composed in LA for me. So it’s a journey across time and space, across the world, that you can see musically.

There are many aspiring social entrepreneurs out there who are trying to take their passion and ideas to the next level. What is one piece of advice you would give to them based on your own experiences and successes? Learn more about how to become a great social entrepreneur from all of the TED Fellows on the Case Foundation’s Social Citizens blog.

Something that I learned from Derek Sivers, who has spoken at TED very often: “Just do it.”

Another thing I’ve learned from amazing social entrepreneurs at TED is that you don’t have to ask for money first. You don’t have to build up this base of funding and then go and start. It doesn’t work that way. If you have an idea, whether it’s an idea the world thinks is nuts, or it’s one the world embraces, go and do it. Ask for money when you establish that base of what you’re doing.

Ideas evolve. Tim Harford’s TEDtalk talks about “The God Complex,” where people have an idea and think it’s the one and only way things should be done. But it doesn’t work that way. You have to find a way, do it, be wrong, then find a way that it evolves and works.

It’s pretty unusual for such an accomplished musician to have a background in neurobiochemistry. How did you find yourself studying the two disciplines?

I always played music growing up. Then as I started college, my parents said, “Ok, you have a choice. You can either be a doctor or a musician, and you’re going to be a doctor.”

So I still studied music, but I started a degree in pre-med biology. And I loved it. I started a few research internships in neurobiochemistry. While I was at Harvard, I was introduced to Gottfried Schlaug, a researcher who had done work on music and the brain. In one of his experiments, he had given singing lessons to stroke victims who could no longer speak. He found that after 70 or 80 hours of singing lessons, the stroke victims recovered some ability to speak again. It totally blew my mind.

Gottfried himself was a musician, so I asked him, “How was it for you, leaving music behind, and becoming this amazing scientist? I would love to do this, but I still really want to play music.” He looked at me and said, “If I could go back and choose between music and medicine, even knowing what I’ve accomplished now with science, I would still choose music.”

And that was exactly how I felt about music. From that point, I decided for myself that I had to find a way to play music. So after that, I went to Yale for two years and did a master’s in music there. I had no idea what I was going to do next.

I thought that I would probably have to give up playing and go to medical school and not professionally play. But I wanted to try at least one orchestral audition. I figured I would flunk out the first or second round. But I got the job. It was a shock. It was a shock for about two years.

It seems a part of you felt it would be better for the world if you had chosen to help people by being a doctor. Have you made peace with your decision?

Sort of. After I moved out to L.A., I met Nathaniel Ayers, which I talk about in my TEDtalk. And that was an epiphany for me. I saw that I didn’t have to be a doctor to make a difference in this guy’s life.

When I was with Nathaniel, there was this moment when he was starting to have a manic episode, and it was pretty scary. But I just picked up my violin and started playing. I think if he had been in a clinical setting, it would have ended very negatively. He would have been tied down, he would have been pumped full of drugs. Both parties would have felt horrible about what would have happened. But music spoke to him where words failed. And the music calmed him down. It brought him to aspects of his life that were too painful to bring up otherwise.

I learned that the music wasn’t only about creating this space in the hall. I learned the music could exist at a very strong level outside Disney Hall. And when it did that, it could actually be medicinal. It could be therapeutic. There have been other cases like that, where music has strongly affected people I’ve played for — people with cerebral palsy and veterans.

I had always felt that music was very powerful, and ought to be brought to places outside the concert hall, but I didn’t have a medium through which to express that. Somehow TED made me feel fearless, and address the idea I had been thinking about for years.

My TED talk was titled “Music is Medicine, Music is Sanity.” I want to prove it. I just had a meeting with neuroscientists from the University of Southern California that are starting a brain and creativity institute there. I also have plans to work with neuroscientists at Claremont College. I’d like to implement their findings of how music is therapeutic, how it is effective, in the field itself.

While playing music for people with mental and other illnesses, you’ve found your music to have a very soothing effect. But can music be more than just a sedative?

Yes, there will be more that it can do when I involve those people themselves in making music. The next step is to create some kind of workshop where the music is active and hands on. Playing music, being actively engaged in a creative process, is what is really incredible.

Why is that creative process so important? What do you believe it does?

It’s really incredible. I found that when Nathaniel actually created music himself, he wasn’t delusional.

Nathaniel’s delusions only exist in his head. Playing music is a way to get that delusion out of his head — to literally express that. When he expresses it, when he hears it, and when others hear it, it’s real. It does exist, even if it doesn’t make sense in his head.

I’ve read the biographies of musicians like Beethoven and Brahms, and they were obviously what today we would have diagnosed as bipolar, schizophrenic or otherwise mentally ill. Music offers people some grasp of reality — maybe it is sanity.

We can express things and create from our innermost soul, whether we are mentally ill or not. So what I’m looking for is a way to remove the stigma of mental illness and homelessness, and show that this music unifies us. The creative impulse that we all have unifies us.

How did you first fall in love with the violin?

Growing up, there was always music in my house. My parents are very musical. They’re Bengali, and they would always tell me Bengal was the land of poets and artists and musicians.

When I was three or four, I guess I would always be dancing around and singing, so they took me to a local music teacher. I was going to play either the piano or the violin. I saw the piano and I started bawling. It was this giant, stationary thing, and I wanted to dance around while I played music, apparently. So I started playing the violin through the Suzuki program. I’d listen to music all day long, then have a medium to play it, and I was thrilled by that.

So we just kept on going. After two years, the local Suzuki teacher said, “I can’t teach him anything anymore. Take him to this teacher in New York City.” So we went to a Julliard pre-college prep school, called School for Strings. I started there, and my little brother, who played piano, and I started there. From there, we went to Julliard pre-college.

Was it a challenge for your parents to dedicate so much to your musical education?

My parents are not musicians, but they were incredibly devoted. My mother would sit in the lessons with me, and she would practice with me. When she found that I was talented, and this was something that was essential for me — that I really loved it — she quit her job and would take us all over the world so we could perform.

My parents had monumental battles with the school district that I grew up in. When I came back from my debut in Tel Aviv with the Israel Philharmonic, my school district didn’t let me take midterms or finals, and failed me. I was growing up in an Indian household — there was no way my parents were going to let me slack off on real studies. I was doing work for the next grade at the time.

So they pulled me out of the school district. The district then sent Social Services knocking at the door to take my brother and me away. So they put me back in school after skipping one grade, and I kept getting beaten up, because I was so young. We changed schools and the same thing kept happening. So we got out of the school district. I took my SATs when I was 11, I took a high school equivalency exam, and I started college when I was 13. They homeschooled my brother, and he started college at the same time.

We wanted to keep playing, but also get a real education that we could count on college credit-wise, so we’d end up with a degree. So if anything happened — if we had some kind of injury or the career didn’t work out, we’d have something on the side.

I started a second undergraduate at Manhattan School of Music, and worked on two undergrad degrees at once. Mount St. Mary’s College, where I was doing my pre-med degree, is in Upstate New York, and Manhattan School of Music is in Harlem. So my mother was driving me back and forth three times a week, 65 miles one way, and my brother to Julliard on Saturdays.

After two years of that she collapsed. She had three non-malignant tumors in her uterus because of the stress. It couldn’t happen anymore. That’s when my parents sat me down and said, “You have a choice. And you’re going to become a doctor.” I was devastated. But I transferred to a different college, and I got my internships, and I started to see that biology was something I really loved.

But I didn’t play for a year and a half. And that was very tough for me. After I spoke with Gottfried Schlaug, though, I decided I had to go back to music. So I went to Yale for my master’s.

A year and a half without playing? Many musicians might not have recovered from that long of a hiatus.

In fact, that time away shattered my confidence. I had to reteach myself every tiny technical detail. But I’m so grateful for that now, because I’ve redefined what works for me on the instrument.

I feel like I generated a real love and passion for the music when I took that time away. I started listening to other types of music. It was the first time I’d listened to Led Zeppelin. I found what I love about music, period.

And I’m still learning new things I love about music. At my first TED in 2010 there was also a ukulele player, Jake Shimabukuro. We had a late-night thing where we started jamming. I had never jammed before. I was scared stiff. And Jake was like, “Just let it go, man.” I had just never thought that way. I have to, you know, look at a page and learn everything I play, and memorize all the notes. It’s never off the cuff. So that was a freeing experience, and I want to do more of that.

A TED Fellow, Josh Roman, who I performed Halvorsen’s “Passacaglia” with, introduced me to Radiohead. I really, really love RadioHead. Now, before big concerts, when I’m nervous, I listen to RadioHead. They’re incredible musicians.

Comments (6)

Pingback: Classic rock: Dan Visconti, the 21st-century composer - The Online List

Pingback: Classic rock: Dan Visconti, the 21st-century composer | BizBox B2B Social Site