The Fez River winds through the city’s medina — Fez’s historic medieval center and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Heavily contaminated, almost an open sewer, it was covered over with concrete to contain the smell; it was all but forgotten in recent decades. For much of the past 20 years, architect and engineer Aziza Chaouni has been battling to restore it. Working with the city’s water department since 2007, she’s now restoring and reconnecting the riverbanks with the rest of the city, while creating open, green public spaces, allowing the medina to breathe again. At TED2014, we asked her to tell the story of this extraordinary task.

The Fez River winds through the city’s medina — Fez’s historic medieval center and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Heavily contaminated, almost an open sewer, it was covered over with concrete to contain the smell; it was all but forgotten in recent decades. For much of the past 20 years, architect and engineer Aziza Chaouni has been battling to restore it. Working with the city’s water department since 2007, she’s now restoring and reconnecting the riverbanks with the rest of the city, while creating open, green public spaces, allowing the medina to breathe again. At TED2014, we asked her to tell the story of this extraordinary task.

How did you begin the task of uncovering the Fez River?

The whole story actually started as my thesis at Harvard. My thesis advisor told me to do something “that you feel passionate about and that could make a difference.” For years, I’d seen the river in my hometown being desecrated, polluted and filled up with trash and rats. It had become an open sewer and a massive trash yard at the core of the city.

The Fez medina has about 250,000 inhabitants, and all their untreated sewage went straight into the narrow river that runs through it. The river was also heavily contaminated by nearby crafts workshops and tanneries — with chemicals such as chromium 3, which is lethal. People working in the tanneries were getting skin cancer, and some of them were dying. It was terrible. Obviously the river started to stink, so people started building walls to block the view. Then, because it became a health hazard, they covered it with concrete starting in 2002. And because it was covered, people began using that open space as trash yard.

Actually, the first covering began in 1952, when Morocco was still a French protectorate, but it was for political reasons — so that French colonial power could easily enter the medina and control the population. Then, as the population grew and Morocco became independent, covering happened because of the stench.

In your Fellows talk at TED2014, you showed how the water feeds into both public fountains and those in private courtyards. Do people actually use that water? Were they getting sick?

Of course they were, especially from the toxic chemicals dumped in the river by craftsmen. It became dangerous to drink from a running fountain. Besides, a series of droughts and excessive extraction from the water table left little water available for the medina water network. By the 1980s, most of the fountains had become defunct, yet they had been central to its urban fabric. Imagine if Rome had no more running fountains! Can you imagine La Seine or the Thames being suddenly covered? The Fez River is smaller in scale, but the effect is similar: a central part of the city was amputated. When I witnessed all this, I was in college at Columbia University in New York at the time. I would have been 19. I was outraged; I wrote an article in the newspaper and I received hate mail, because of course it made the city look bad. At the time, I was an aspiring engineer. But due to my age and lack of experience, I was not taken seriously.

Contaminated water will also have been entering your food supply, your groundwater.

Of course! Yes! Yes and yes and repeatedly yes. It would pollute the water table, which feeds the most fertile agricultural basin of Morocco. But this didn’t upset anyone. Environmental protection is almost seen as a luxury in developing countries: economic development, health and education are understandably bigger priorities. It’s a different mentality in Morocco. I heard many times: “Look, we’re eating the food and we’re fine, hence nothing’s wrong!”

Many people are eating food exported from Morocco.

I know. And of course it’s not just Morocco — in so many emerging countries, you have high levels of environmental pollution, but you just don’t know about it as there is not much control or accountability. But the point is that if you uncover such a large-scale environmental hazard, even as an architect, you feel outraged and want to do something about it. So I decided, for my thesis, to propose re-envisioning the medina if the river were to be cleaned and uncovered.

My thesis took a slightly different approach to what I’m doing now. You see, the medina of Fez used to boast one of the oldest universities in North Africa, the Quarawiyine, but after Morocco’s independence in 1956, the government established an American style campus outside the city, which symbolized modernity. The university’s move caused the entire cultural life of the city to fade away. In my thesis, I proposed building a university in the medina, with the various departments to occupy the urban voids along the river. These voids had been created when the river was covered: houses were destroyed to make way for the heavy machinery required. My vision was that, once uncovered, the river would serve as a pleasant green feature, and its banks would be used as a circulation system linking the departments. Classrooms would be located in nearby abandoned buildings. The university model was unusual and innovative: it would be one of a heterogeneous network of buildings embedded within the medina’s urban fabric.

For me, bringing back the water and the university represented a double win. The university idea hasn’t happened yet, but working on this thesis allowed me to start thinking about the potential of the river for the city and its inhabitants. Many ideas I developed back then became a solid departure point for the actual project, which I started in 2007 in collaboration with my then-partner Takako Tajima.

You’d been thinking about uncovering the Fez River for almost 10 years by then. How did the Fez River Project become a reality?

When Takako and I learned in 2007 that the city would finally be diverting and treating the medina’s sewage, we knew that with clean water, it would be possible to uncover the river and use its banks. We could create much-needed green, open space in the medina. It only has 43.5 square feet of green space per person, while UN standards recommend between 215 to 275 square feet per person.

Inside the medina, the uncovering of the river opened up new possibilities to restore the river banks as pedestrian pathways, reconnect the river banks to the city fabric and transform what used to be urban voids into green, open spaces. So we proposed three main interventions: a pedestrian plaza, a playground and a botanical garden. We used four main strategies: precisely placed interventions strategically phased to enhance water quality, remediate contaminated sites, create open spaces, and build on existing resources for economic development. These interventions had to benefit the population on several levels — social, environmental, economic, urban — and be resilient, so that it would still function regardless of changes in budget, political climate, and so on.

At the wider city scale, we needed to prevent the newly cleaned river water inside the medina from getting polluted upstream, so we recommended measures for improving regional water quality, too. Depending on soil geomorphology, levels of water pollution, adjacent urban fabric and ecological systems, we purposefully located various rehabilitation tactics like canal restorers, constructed wetlands, bank restoration and storm-water retention ponds.

Before: A portion of the Fez River before its uncovering. The concrete plaza being used as a dump and the blue marks indicate the location of the river. Image: Aziza Chaouni

Now that the water is clean, is biodiversity coming back?

Not inside the medina, but downstream. The changes in biodiversity are definitely noticeable: the flora looks more healthy. Inside the medina, there’s now construction, and craftsmen have not completely stopped polluting some areas of the river and its banks. So it’s more of a long-term goal, but it will happen.

It sounds as though you met with a huge amount of resistance. Yet now, the Fez River Project is celebrated. How did this happen?

The moment things changed was when we won two very important design prizes, called the Holcim Award for Sustainability in 2007. It’s one of the most lucrative prizes — up to $400,000 for the Gold Regional and Global awards — in the design field. The prize brought the Fez River, its problems and potentials to the attention of a large public. When something becomes that important publicly, there are many new stakeholders that emerge — everyone wants to help the project while projecting their own agendas. Suddenly, many voices started to be heard. But sadly, our input was seen as less necessary or relevant. So it became something of a battle.

Why is having many people interested difficult?

Having many voices interested in architectural and urban issues is a positive thing in many regards: for example, it can allow for a democratic design process. However, it can sometimes also create hurdles and harm a project as it dilutes its central design ideas. As some of my colleagues have observed, any municipal project around the world is the most complex project you can possibly work on, especially on a large scale. Because there are just so many variables, there are so many changes in the sociopolitical landscape, and so many commercial and economic interests colliding.

After: What this portion of the river above will look like once it is uncovered, and the area shaded built to create a public plaza. Image: Aziza Chaouni

But fortunately, there is no turning back now. The river is uncovered — a process that took three full years — and the first public space is almost finished. It’s a plaza. People are using it, even though it is still under construction. So, no matter what the design ends up looking like or how people change it, at least the worst has been avoided: the river could have remained terribly polluted and its existence even forgotten by the inhabitants of the medina, erasing a large part of the history of the city. Like in other other medinas in the Middle East, the covered river could have easily become a vehicular road, which is a harbinger of bad news for medinas.

When roads are introduced into these medieval cities, their pervasive pedestrian network starts to slowly be transformed. Narrow pedestrian streets become larger and are gradually replaced by roads. Also, once-inward-facing houses start to open up with businesses facing towards these new, large roads. As a result, the medinas’ urban fabric loses its unique character, which is marked by an organic, labyrinthine pedestrian system. The medinas of Tunis and Algiers illustrate well this tragic, irreversible transformation.

How many more years before your final vision comes to pass?

For me, on a fundamental level, I would say that the core of our vision has happened: the river has been resuscitated, both figuratively and literally. It is uncovered and acknowledged by all as a “river,” not a sewer. This presents a unique potential for the medina of Fez. A key lesson we have learned is that a resilient design project, with a solid core idea, can surmount any changes that come its way. Its core idea will remain, even though its aesthetics, timeline, methodology will drastically changed. In architecture school, we are taught that one’s project should be implemented as closely to one’s drawings as possible. In developing-world contexts, especially while working on municipal projects, this task is almost impossible. The architect needs to leave his or her ego in the back seat and develop a resilient, phased design with key principles that can sustain changes of stakeholders in the socio-political sphere, with the economic landscape and so on.

How much are you invested personally in the Fez medina? Did you grow up here?

My dad and my grandparents on both sides of the family were born and raised in this medieval city, so it’s absolutely very close to my heart. I grew up not inside the medina, but in the newer part of the city, right next to it. What’s amazing is that it’s not a place for tourists — it is a living city, and not much of its urban fabric has changed since the 7th century. People live there, work there — so if you want to buy, for example, a type of cake, special fabric, sweets or pickles, it can only be sold in certain neighborhoods of the medina. Tourists do go there as well, of course, but the medina of Fez has not given way to massive gentrification.

It sounds magical.

When my American mother-in-law, who’s a historian, came to Fez, she said, “I never felt so much that I was back in time, back in the medieval era. You almost forget which time period you’re in.”

You call yourself a nomad, and work on quite a few other projects around the world, specializing in eco-tourism in arid regions. But your work in Fez must take up a huge amount of time.

Let’s say I am a semi-nomad with a double life. I am an assistant professor at the University of Toronto, and I have a small design office with two people in Toronto, and an office of five people in Fez, my hometown. I usually spend about three months of the year in Fez, and I keep daily contact with my team and clients while I am in Toronto.

The nice thing about the University of Toronto is that it’s a research university, so I am expected to work on research projects. Obviously, I like to link my research to my practice, as they both feed on each other. I’m not an architectural historian — I teach students to become professional architects, so it is a big asset to be practicing, especially in countries like Morocco. That way, I can share with my students design expertise specific to developing world contexts.

I also have an applied research lab called DET at the University of Toronto that focuses specifically on ecotourism in emergent countries, in very remote areas. I have been focusing on deserts and arid climates these past years, and I have worked on projects in Southern Morocco and Jordan.

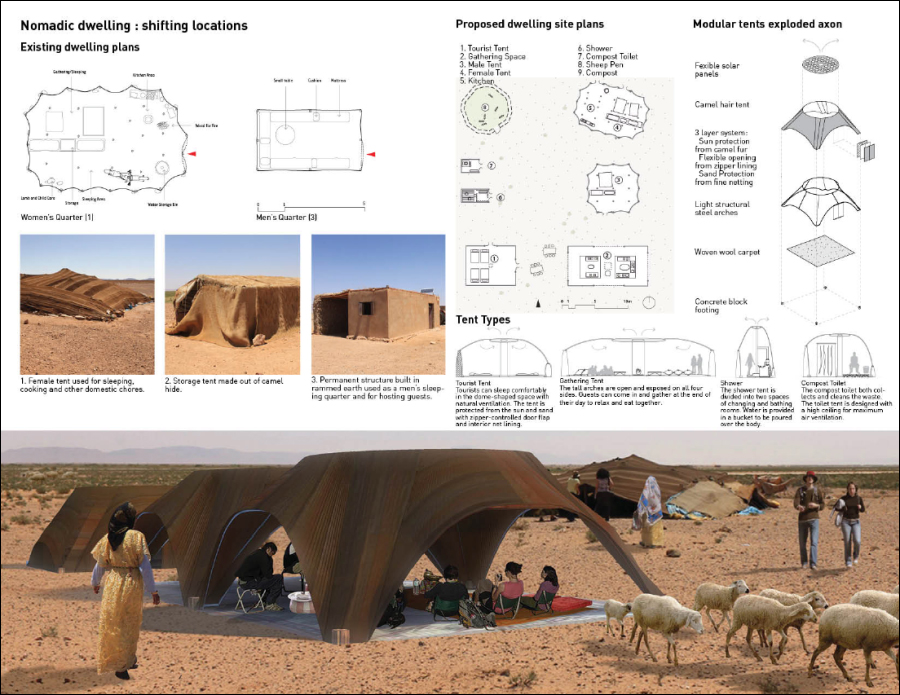

Proposed dwelling sites for an eco-tourist destination in Ain Nsissa nature reserve, Morocco. Image: Aziza Chaouni

Can you give us an example?

Well, we work with the Moroccan Ministry of Tourism, for example, when they need to set up guidelines for investors to develop tourism projects in fragile, remote sites. Of course, Morocco is a developing country, and they want outside investors, but they also know that if they just let people do whatever they want, they will mess up those landscapes. In a desert, there is no margin for error. You mess it up, you kill everything, and that’s it. You’re all done. You have so few resources, too. So investors can be scared to come in.

With the help of my mentor and thesis advisor, Professor Hashim Sarkis, I was able to convince the Moroccan Ministry of Tourism to finance my students’ trips to Morocco. Then, under my guidance, they develop innovative solutions and guidelines, which then become bylaws. We started developing, for example, new types of ecological nomadic tents that leave very little impact on their context—they fold up and can be moved easily.

Then, I was asked to work in Jordan by the Royal Society of Conservation of Nature (RSCN), also in a desert area, to help them establish a new protected area north of Petra called Shobak. RSCN, an NGO, runs all national parks, not the government. Since they only receive 10% of their money from the government, they need to generate the other 90% to conserve nature. So they rely on eco-tourism, and wanted new ideas about how to develop it. The fact that I speak Arabic, and that I can also easily speak to women because of my gender, has been a big asset to understand the aspirations of local populations. A lot of men from these remote areas migrate to cities, so mostly women are left.

And you’re working on a Canadian project, as well?

Yes, after I’d been to Jordan, I collaborated with Parks Canada in Toronto to study the first very urban national park in Canada, Rouge National Urban Park, created in 2012. I applied for a grant to compare Rouge Park, which is right in the middle of the suburbs, with another urban national park in Rio, Guaratiba Biological Reserve, which contains a unique mangrove habitat. Both parks are adjacent to large, sprawling cities, and they will be under even more pressure in the future. How can we manage parks like this in new ways? How can we build next to these new parks?

Thanks to a LACREG grant, we did research for two years, then created an app that compares the two parks — how they are run and funded, their adjacent urban areas, their leisure activities, their ecosystems, endangered species. But the part we’re most proud of is that we created guided tours with a feature that allows visitors to become stewards of the park by reporting environmental abuse. Because these parks are usually not well-known, people can take different tours that will explain their history. But the most important issue is that urban parks are very hard to manage because they are readily accessible, and park rangers have a hard time being vigilant. So the app allows anyone who sees something or someone harming the parks — such as littering, poaching, off-leash dogs, harming wildlife — to take an image, immediately upload it to Flickr, and geo-tag it.

Comments (21)

Pingback: Moving Medinas Into the Future – ALL I NEED IS MY PASSPORT

Pingback: 10 Tips for Finding Ethical and Sustainable Fashion in Morocco - Ecocult

Pingback: Fascinating Fez, Morocco – Gorgeous Unknown

Pingback: المغرب: 12 قرناً من التراث مهددة بالزوال في مدينة فاس ...السياحة ليست كلها ربحاً!! -

Pingback: السياحة ليست كلها ربحاً.. 12 قرناً من التراث مهدَّدة بالزوال في مدينة فاس المغربية | جريدة الدراركة بريس

Pingback: السياحة ليست كلها ربحاً.. 12 قرناً من التراث مهدَّدة بالزوال في مدينة فاس المغربية

Pingback: The threat to Morocco’s Fes from tourism surge | Breaking News | Travel Wire News

Pingback: The threat to Morocco’s Fes from tourism surge | World Affairs 7

Pingback: Fes - kulturna i duhovna prestonica Maroka | TAMO VAMO

Pingback: I Beg of Y’all: Drink from my Wetland – Musings for More

Pingback: Finding Friends in Fes | A Move to Morocco

Pingback: Aziza Chaouni: “How I brought a River and My City back to Life” | SANDRP

Pingback: Making better places and spaces: Aziza Chaouni Projects | | Canadian architectural practices, their projects at home & abroad, and the broader built environment

Pingback: Aziza Chaouni Projects » Chaouni interviewed on the TED blog

Pingback: From sewer to jewel: Aziza Chaouni on uncovering the Fez river | TEDFellows Blog