Cameron Russell and art director Hannah Assebe think over an idea for the redesign of the Interrupt magazine website. They can’t wait to show off the final product in September. Photo: Becky Chung

In the chaotic heart of downtown Brooklyn, a door greets you with an illustration of a man in a pink tutu and leopard print leggings tossing up a peace sign. Welcome to Space-Made—the art lab where Cameron Russell and her collaborators create Interrupt, a magazine that lets marginalized communities tell their own stories. It’s a concept that the supermodel felt compelled to launch after her TED Talk, “Looks aren’t everything. Believe me, I’m a model,” went viral.

At a table, near the bubblegum machine and shelves full of photography books, Russell and Interrupt’s art director, Hannah Assebe, go over the latest wireframes for their website redesign. Fresh copies of Interrupt’s fourth issue, themed “I Live For That!,” are stacked next to them. For this issue, which explores the bounds of LGBTQ love, Russell and Assebe tried something unusual: rather than curate the magazine themselves, they appointed two outside groups as co-editors-in-chief—Project SOL, a LGBTQ teen group, and HOLAAfrica, a pan-African Queer Feminist Collective. The results were a fiery and fresh publication like no other. Russell and Assebe learned a lot from this collaboration, and are using the experiment to help them with the next iterations of Interrupt.

Cameron Russell: Looks aren't everything. Believe me, I'm a model.

But before we talk about where they’re going from here, let’s rewind a little to where it all started: at TEDxMidAtlantic in 2012. Russell gave a bold talk at the event, admitting that becoming a model was easy because she happened to to have won the “genetic lottery” of being white, pretty and privileged. In the talk, Russell shared her surprise at how often young girls want to know how they too could be models. “Why?” Russell asked on-stage, “You can be anything. You could be the President of the United States, or the inventor of the next Internet, or a ninja cardio-thoracic surgeon poet, which would be awesome, because you’d be the first one.” In her talk, Russell stressed that modeling is not a sustainable career path. “You don’t have any creative control,” she said.

Cameron Russell: Looks aren't everything. Believe me, I'm a model.

But before we talk about where they’re going from here, let’s rewind a little to where it all started: at TEDxMidAtlantic in 2012. Russell gave a bold talk at the event, admitting that becoming a model was easy because she happened to to have won the “genetic lottery” of being white, pretty and privileged. In the talk, Russell shared her surprise at how often young girls want to know how they too could be models. “Why?” Russell asked on-stage, “You can be anything. You could be the President of the United States, or the inventor of the next Internet, or a ninja cardio-thoracic surgeon poet, which would be awesome, because you’d be the first one.” In her talk, Russell stressed that modeling is not a sustainable career path. “You don’t have any creative control,” she said.

As Russell hopped off the stage, she started cooking up an idea: to create her own magazine. She initially wanted to create a publication for audiences outside of mainstream fashion. “I felt like fashion was this really tiny world. You know everybody. You don’t work with new people very often. It’s the same characters,” she remembers. “I noticed many fashion bloggers, who were the same people being marginalized from mainstream media, and I thought a magazine format could pull them all together.”

Russell ended up moving away from this vision. But the idea of featuring new voices and faces paved the way for Interrupt.

For Russell, the conditions for growing an experimental magazine seemed perfect. Before her TED Talk, she and a small team had already been playing with community storytelling through her art-meets-activism collective Space-Made. “We thought art really engages a massive number of people. What if that could be translated to a political action?” she explains. Space-Made’s mission prioritized the voices of women, people of color, LGBTQ, low-income and other artists from often-marginalized communities. Over the years, their projects included a writing workshop following the Zimmerman verdict for 16- and 17- year olds, interactive technology courses for seniors and an art hack day around the topic of campaign finance reform.

Cameron Russell shot down the idea that it’s “hard” to be a model at TEDxMidAtlantic. Her talk quickly went viral. Photo: Courtesy of TEDxMidAtlantic

Meanwhile, as the views of her TED Talk climbed, Russell noticed a power stemming from the avalanche of media interest around her talk. “I didn’t see the point in rehashing the same narrative, my own story of being a model. It was getting stale,” she says. Instead, while she had the spotlight, she thought she could show what others were working on instead. She posted a letter on Tumblr: “Can we reroute this press deluge… to create opportunities for more of our voices to get heard in the average news cycle? Let’s try and use it as a platform to say what we want. Let’s put forward a diversity of radical ideas; let’s showcase the programs and organizations we make strong.”

Russell found herself flooded with stories from all walks of life—stories that cracked open social perceptions often seen in mainstream media and that highlighted voices on the fringe. Russell explains, “I was thinking about access to media and it clicked: What if we build a space for media-makers who don’t have it?”

In the Interrupt office, Russell and Assebe tell the story of how their “participatory” magazine, which devotes its pages to the work of these media outsiders, came to be. They also reminisce about how they first met—when Russell hired Assebe to make the slides for her TED Talk. “I didn’t think you were a model when I first met you,” recalls Assebe.

“I get that a lot, actually,” says Russell. “Tons of people come up to me to ask about my TED Talk now, not about [modeling]. I feel it’s easier to remember someone if you’ve been staring at them speak, than if you’ve flipped past their photo in an ad. You’ve invested time in hearing what they have to say.”

With the help of Assebe and the Space-Made team, Russell launched the first issue of Interrupt Magazine, “Put Me On TV!” with essays and videos from women all around the world who are working to improve media representation. In subsequent issues, they let readers vote on themes. Issue two, called “Lips, Tits, Zits, Thighs, Eyes and Muffin Tops,” their first print publication, was designed to look like a tabloid, but with more thoughtful content than what you’d find in People or InTouch. The cover teased stories about plus-sized models, journal entries of young girls who love their bodies and an essay and photo documentary by writer H. Tucker Rosenbrok on his transition from female to male. Issue three was a digital collection of stories on race.

With issue four came the co-editors-in-chief experiment. Russell and the team decided not just to feature work of outsiders, but to have community leaders curate their own issue. With this, the purpose and editorial strategy of Interrupt Magazine have begun to shift. “I have resources—filmmakers, editors and graphic designers. Why not pass those off to a different editor-in-chief every time?” asks Russell. “Like elected officials have term limits, we decided to have them for our editors too, to keep the ideas and the voice of Interrupt fresh and bring new audiences each time around.”

Editors-in-chief have full freedom over how their stories are told, says Russell. The even have full control over the theme. This new strategy even includes thinking of an issue as a content package, or an experience, with Interrupt at its center. To complement issue four, Space-Made simultaneously launched “We Are The Youth,” a book of portrait photos of LGBTQ youth in the United States and their stories in the form of as-told-to essays.

Because Interrupt focuses on communities and groups who rarely see their stories told in magazine form, Russell aims to distribute issues directly to their respective communities. Copies of issue four, for example, will be available in LGBTQ youth shelters in New York.

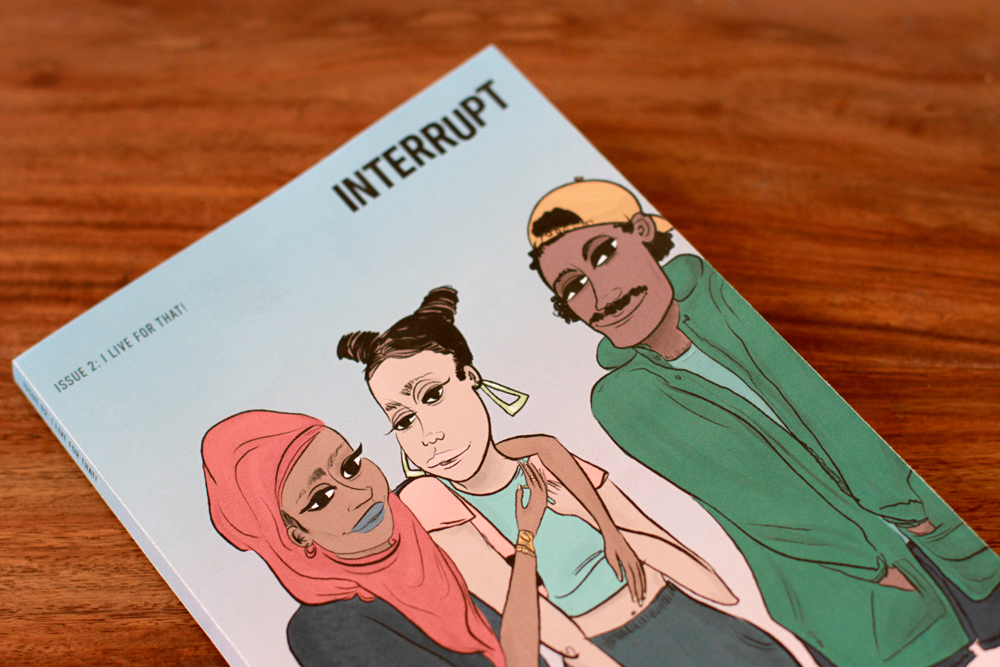

The cover illustration for issue four, “I Live For That!” was drawn by Mohammed “MoJuicy” Fayaz. (Who also made the illustration on the door of Space-Made.) In an editors’ note, Project SOL and HOLAAfrica! write, “This issue is an effort to represent the way we see the world and ourselves. It is not meant to speak for all LGBTQ youth, but we hope to inspire people to create their own stories and media.” Photo: Becky Chung

“I’m totally fascinated by undervalued leaders and experts,” says Russell, “Why does our media ignore them, why does our electoral system ignore them? I wanted to build a sustainable platform for them—be it a magazine, a media outlet or a physical space, a network. I think there are a lot of different iterations.”

Whether digital or print, each issue of Interrupt feels substantial. And each feels reminiscent of the zine era thanks to its size, its DIY sensibility and its small, concentrated doses of content that kick you in the head. Class mobility, foster care and DIY feminism will be themes of future issues, says Russell, each with its own unique editor-in-chief and distribution strategy.

While working on the upcoming issue about class mobility, the newest editor-in-chief Lynn Cyrin, an advocate for the rights of transwomen and homeless women, told Russell a story: Most homeless shelters in San Francisico do not have wifi—a huge roadblock because it prevents the homeless from having access to the rest of the world via the Internet. When she was homeless, she taught herself how to program. Russell noticed a thread with other editors-in-chief that Interrupt is working with: “Because they are experts of their communities, they are identifying places where resources are not going.”

Russell and her team think a lot about how their platform can keep helping creators lead the conversation, and how they can continually support the editors in their future work and causes. Interrupt’s redesigned website, to be revealed in the upcoming months, will further explore this idea. Not all issues will have a print or an interactive component—but all will be on the site. Each new issue will take center stage while older issues will exist on a separate page, so that they can continue to “interrupt” the conversation. Russell and her team are also brainstorming the best ways to help readers dip their toes into the activism waters. The current iteration of the site helps readers learn how to get involved in the social causes brought up in different issues, but they think they can do more.

In addition to running this ambitious, big-vision magazine, Russell is still modeling. “In the last two years I’ve been more successful as a model than I ever have been,” says Russell. “Eleven years of it later, I’m still trying to find how it’s useful.”

When she started modeling, Russell assumed that the job would phase out after college—she thought it would be something with a definitive expiration date. But while it’s never what she imagined doing for her career, she maintains that it has been useful for giving her access to experiences, and that it has financially helped her get an education and start projects like Interrupt. In the end, she’s embraced it as a part of her identity.

Russell is a model, but she’s also an activist, a writer, an editor, a curator and a publisher. As she moves forward with Interrupt, she wants to help leaders become media-makers and media-makers become leaders. Even when she’s contemplating her own career path, she returns to thinking about the work of her collaborators. “We hope our investment in their editorship could be a sustainable one that will matter beyond the scope of the issue,” she says. “We want it to keep on having an impact—on their careers and on their communities.”

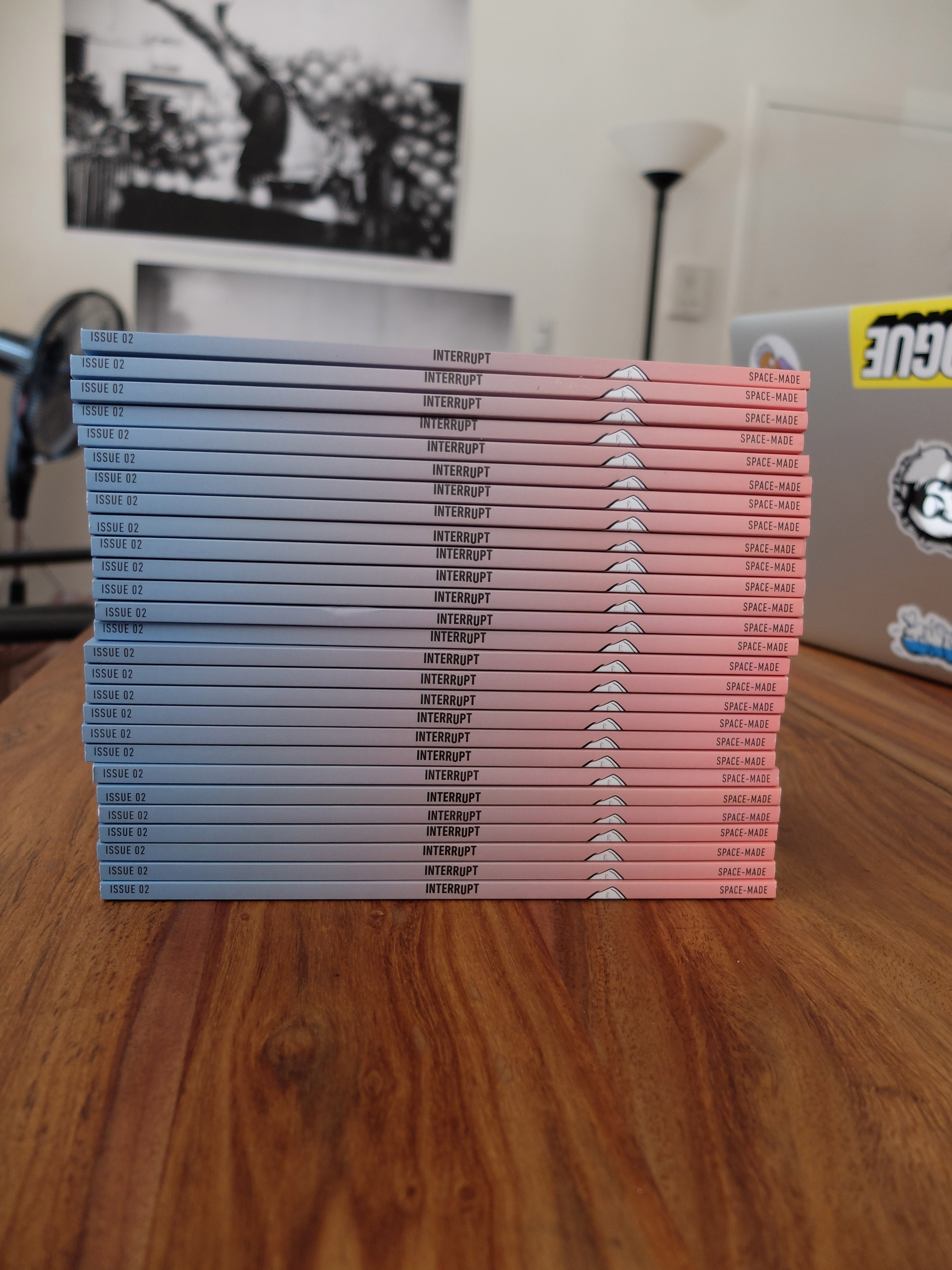

At the end of this issue, there are helpful listings for local New York-based LGBTQ youth groups, programs, hotlines, homeless services and health care assistance. This stack may end up in one of those locations. And for a reader who might not be familiar with terminology, a mini glossary defines everything from “cisgender” to “two spirit.” Photo: Becky Chung

Comments (2)