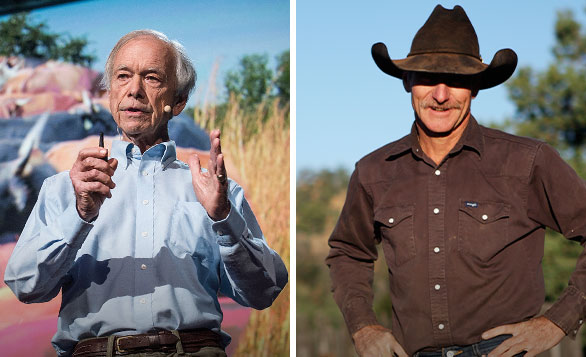

Allan Savory is a biologist who has spent a lifetime trying to save degraded land. Gail Steiger is a rancher and filmmaker who has long followed his work. Below, what happens when the two talk. Make sure to read to the end for the stab-you-in-the-heart final question.

All over the world, land is turning into desert at an alarming rate. Biologist Allan Savory has dedicated a lifetime to figuring out what’s causing this “desertification.” Finally, after decades of work in the field, Savory discovered a radical solution—one that went against everything scientists had always thought. He used huge herds of livestock, managed to mimic the behavior of the natural herds that roamed grasslands centuries ago, and saw degraded land revert to robust ecosystems.

Here, Savory talks with rancher, performer and acclaimed filmmaker Gail Steiger about his new TED Book The Grazing Revolution: A Radical Plan to Save the Earth, detailing his remarkable and often difficult journey to discovery—one that ultimately ends with great hope for the future.

Gail Steiger: First of all, I’d just like to thank you for all that you’ve done for—actually, for the world. I’ve been familiar with your work since your book in ’88. Lots of my friends here in Arizona attended your school, and you’ve just made a great contribution to all of us. Can I ask you for some historical information? Tell me a little bit about the most valuable experiences that informed your thinking today.

Allan Savory: Oh, gosh. That goes back a long way. Let me just start before I left university and joined the Game Department, in what was then Colonial Service, in Northern Rhodesia. (It’s now Zambia.) I was very passionate about wildlife, elephants in particular, but also rhino and so on— the big game of Africa. And I had this new, shiny degree, and training as a botanist, zoologist and ecologist. But when I went into the field, I hit reality. What I’d been taught just simply wasn’t making sense. It didn’t match with what I was seeing. To give you an example: We were taught that overgrazing caused desertification. More specifically, that desertification was due to too many livestock, and that the answer was reducing the numbers of animals and burning the grass to keep it healthy.

Well, I was soon engaged in burning massive areas of land to keep the grass healthy. This was land that was to become our future national parks. I couldn’t help but observe the fact that we were baring the soil, and that the bare soil was subsequently being carried away by the rainfall. And as I mention in my TED Book, I actually took to walking in the rain so that I could see what was happening for myself. And just found it was wrong, you know? Of course, I didn’t have answers, but I began very seriously looking for them.

Then came one of the biggest mistakes of my life. Because the land degradation was so bad, but there wasn’t any livestock on it, I proved the problem must be that there were too many elephants. And the government, after investigating my book and approving, shot 40,000 elephants. But the desertification only got worse, and it’s still getting worse to this day. As I look back, one my biggest findings came from trying something, making a mistake and saying, “Well, why did it go wrong?” So actually some of the biggest findings came from the failures.

Another big finding for me was when I happened to pick up a farming magazine off a coffee table in a farmer’s house and read an article by John Acocks. John was a botanist studying the extension of the Karoo Desert bushes taking over what had been grassland. He had concluded that the land was understocked—was carrying too few animals—but was overgrazed. So he said South Africa was deteriorating because of overgrazing and understocking. This caused a furor in the scientific community. Acocks was ridiculed, but to me it was brave new thinking. I actually drove all the way down to the Cape to go and see him personally and was able to visit some of the ranchers he was working with.

Allan Savory: How to fight desertification and reverse climate change

Now, I’m always looking for places where something different is happening. Some people call that “positive deviance.” I spotted one such deviance while I was visiting a ranch: A patch of land that was visibly much better than the rest. I got very excited and asked the rancher what had happened in that spot. He told me the sheep he was using had crowded there for a short time. That was a big moment for me, the moment when I suddenly realized connection between what I was seeing there, and what I had first observed with large wildlife herds. That’s when I realized we could possibly use livestock to mimic the wild animals. It was a big turning point.

Allan Savory: How to fight desertification and reverse climate change

Now, I’m always looking for places where something different is happening. Some people call that “positive deviance.” I spotted one such deviance while I was visiting a ranch: A patch of land that was visibly much better than the rest. I got very excited and asked the rancher what had happened in that spot. He told me the sheep he was using had crowded there for a short time. That was a big moment for me, the moment when I suddenly realized connection between what I was seeing there, and what I had first observed with large wildlife herds. That’s when I realized we could possibly use livestock to mimic the wild animals. It was a big turning point.

But the most difficult piece of the puzzle, the one I still believe we never could have discovered in Africa, was that the greatest single cause resulting in desertificaion is overresting the land. And I really believe we could only have discovered that in America. Because when I got here, I found such vast areas of land with nothing on them. I mean, it was almost like being at sea. There was not a sound — not a bird chirp, nothing. In Africa, India, South America, anywhere else I’d been, it was hard to find silence. There were birds, monkeys, something all around you. But when I struck national parks in America with not a sound, and still saw terrible desertification taking place, that was a big horror moment.

GS: In Holistic Management, you talked a bit about your experiences trailing both humans and wildlife, and how that enabled you to see what was actually happening. I appreciate that. The ranch I’m on is pretty rough country, and sometimes we just can’t find our cattle. If you can’t trail, you’re not going to do much good out here.

AS: I spent a lot of my life—20 years of it—in war, training army trackers and commanding a tracker unit, and then in the Game Department, tracking lions, and elephants and poachers. So I’ve spent literally thousands of hours tracking people or animals, and training others to do it. And yes, that was an incredible opportunity; rarely do scientists have the opportunity to be trying to solve a problem on the land, and then spend so many thousands of hours tracking. I mean, we couldn’t dictate where guerrilla gangs would penetrate the country, but wherever they came, we had to go and track them down. And so we tracked in every imaginable sort of county.

Then you have the long nights where you sit and think about it: Why the hell was it easy today? Why was it so difficult yesterday? What sort of land are we on? What sort of climate are we in here? Am I in a national park or on communal land or on a commercial ranch? You’re thinking about it all every night, and the next day you’re tracking again all damn day.

Only many years later did I read the book by Liebenberg, where he explains pretty logically that tracking was probably the origin of science. I think his argument was very good, because a good tracker is not just following tracks. A good tracker is interpreting all the time, from every little sign, you know? Not just interpreting the age of the tracks but also: Is it wounded? Is it hungry? A good tracker is interpreting a lot.

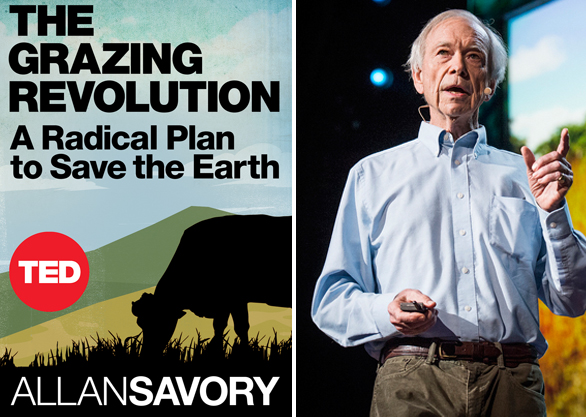

Allan Savory gave a talk with a solution for land degradation that set TED2013 abuzz. Today, he releases the TED Book, The Grazing Revolution.

GS: It certainly led to good work! Can you tell me a little bit about your TED Book? Your earlier works have been specifically targeted to land managers. But of course TED casts a much broader net, and I’m wondering what do you think urban dwellers can bring to the land-management table? What’s your intention there?

AS: Urban dwellers are the only ones that can save the situation. Let me explain that: The bulk of the populations of almost every country have moved to the cities, or are moving there. That’s where the voting power is — the mass of public opinion is. Now the stuff I talked about at TED, we’ve talked about for years. Now you might ask: Well, why did nothing change? At first, I too could not understand. It did not seem logical. But as I grappled with it, I went back to researching other fields to see if there was any reason for this, and I found there was.

Hard systems are everything we’re using right now — computers, phones, planes, the clothes you’re wearing, the room you’re in. Everything there involves 100% use of technology and expertise to make it, and nothing we make — including space exploration vehicles and so on — is complex. Everything we make is complicated. Nothing is self-renewing. If the computer is missing a part, it doesn’t work, or the plane is missing a part, it doesn’t work. It can’t self-organize.

But if we look at human organizations, they are complex. In other words, they do what they’re designed to do, and can be very efficient, be they a university, a hospital, etc. But they—because they’re complex, self-organizing, composed of hundreds of individual humans all interacting—they have what are called emergent properties, things that emerge that weren’t planned or intended. And these can result in what system science calls “wicked problems.” This doesn’t mean they’re amoral — just that they’re extremely difficult to solve.

There are two wicked problems of human organizations. One is that they cannot—they simply cannot—accept new scientific insights ahead of society in general. And so that is why my TED Talk in 20 minutes did more than 50 years of struggle within the scientific community. Because it was seen by—as far as I can make out— over a million people. And so the information is now getting to society. And already organizations that have been aloof or blocked us or resisted are beginning to collaborate with us and change.

So it’s only the people in the cities that can begin to change public opinion or societal view. When there’s a sufficient groundswell, then our institutions can change. We’re not going to be able to stop the desertification of the United States when so much of the land is federal-owned land under government agencies that are trying to save the wildflowers or the horses or stop the terrible droughts and floods that are occurring in America. We’re not going to be able to stop those until the public opinion is deeper, until people understand that there is no option but livestock over most of that land, and that these policies need to be developed holistically.

GS: It would seem like a holistic approach would require us to rethink the entire scientific method. I mean, if you look at education in this day and age, there’s ever more pressure to specialize. The higher level you attain, the more it requires you to focus on ever-narrower subjects, and it seems like we would really have to rework everything.

AS: That’s very much part of the problem. John Ralston Saul points out — after studying what’s happened since Voltaire’s time, the Age of Enlightenment, where we were no longer going to have massive blunders because organizations would be headed by professional-trained people and you could no longer buy or inherit your position — that following that period in history, the blunders increased. He notes that no matter how brilliant the people, no matter how well-meaning and caring, if they’re in an institution or organization, because of complexity, what emerges very often lacks common sense and humanity.

So you can—as I’ve done—talk to city audiences almost anywhere and say: Does it make sense for the United States to produce oil to grow corn to produce fuel? And people just laugh and say: No, that’s stupid and it’s inhumane. Well, thousands of scientists employed and paid salaries by organizations signed off on that. I was in Australia recently and I found it’s a greater crime with heavier penalties for a farmer to sell you fresh, clean raw milk than it is to sell drugs. See, it doesn’t make sense.

Saul attributed that to the education system. And quoting Saul here, he said, “The reality is that the division of knowledge into feudal fiefdoms of expertise has made general understanding and coordinated action not simply impossible but despised and distrusted.”

GS: I remember back in the ‘80s, as ranchers we were under a lot of pressure from environmental groups—they really wanted to remove all livestock from public lands.

AS: Yeah, “cattle-free by ’93.”

GS: Exactly. The idea that industrial agriculture could somehow save us: Could you comment on that at all?

AS: Those environmentalists, they’re trained in the same universities. I understand them, because I also once believed that if we could get rid of the livestock and return to just wildlife, we might be able to stop the degradation of the land. But again, I was wrong, because that became a major multi-billion dollar industry, mainly in places like Texas and South Africa. But every single game ranch without exception that I’ve been on, the land is still deteriorating. I held those same beliefs — that we just had to get rid of livestock — so I understand those environmentalists. In my case, I just saw that I was wrong. And I loved the land and wildlife more than I hated livestock. So I changed.

GS: I have a personal question to ask. Most of us who are involved in agriculture, who are not landowners, have kind of resigned ourselves to the fact that the rewards come in other than financial ways. It seems to me like the best thing about being able to manage livestock on a big piece of land is that every day you get a chance to appreciate just what a gift it is to get to come and live on this planet, you know? And it seems like we operate under this economic system that measures everything in terms of dollars and cents. I mean, most economic theory would say we could measure all goods in those terms, and that doesn’t appear to be a defensible assumption. And the other assumption is that all growth is good, the more the better. It seems like a holistic approach would require that we rethink those things, particularly the one that equates happiness with dollars and cents.

AS: You’re absolutely right. But again, we will not solve this by just taking a holistic approach, although that is necessary. We’ll only solve it by actually developing policies holistically. The things you mentioned just cannot go on. I mean, constant growth in a finite world is just simply not scientific. The use of fiat money — where money makes money—and wealth is accumulating ever more in the 1% — that’s inevitable with the monetary system we have. And then the development, or the measurement of growth on gross domestic product, is just ridiculous. For example, how can it possibly be holistically sound, or scientifically sound, or even common sense to measure your economic growth where you value building jails at the same level as you value building hospitals or schools? What we’re doing lacks humanity.

GS: In a broader sense, what assumptions does our culture make that are most damaging to our planet? It seems that more materialistic we get, and the more we do urbanize, the greater the threats are.

AS: I’ve thought about this for many, many years. For me, it was best summed up at a conference my wife and I attended long ago in Sweden in an address by Gro Harlem Brundtland. She was appealing to the scientists there to see the problems as interconnected. She pointed out that international agencies that she was dealing with at the time were spending many, many millions of dollars on many things: Droughts, floods, locust invasions, poverty, violence, weeds, etc. And everywhere, it’s failing. We’re not succeeding. If we could see the interconnections between these—what’s in common—maybe we could be more successful.

I did a lot of thinking after that, and have continued to over the years. We’re blaming many things. We’re blaming politicians; we’re blaming greed, capitalism. But it’s not that. Because I looked at all the things we were blaming for the situation in Africa: Overstocking, communal land tenure, people not loving the land, the tragedy of the commons, overpopulation, inadequate access to capital. And then I looked at the situation in West Texas and I found the opposite of every one of these things: Private land, people loved it, they weren’t abusing it. No overstocking with livestock, they’d been de-stocking for over a century, consistently. No overpopulation, very low and falling population. Great access to capital wealth. Good universities. But the same problem.

Clearly, there was something else causing all this, and I think it’s this: When you look at agriculture overall, it’s the biggest single problem facing humanity, even bigger than the oil one. Agriculture in its broader sense, you know, the production of food and fiber from the world’s land and waters. Because even after we discover benign sources of energy, climate change and poverty and drought—all these problems will continue because they’re manmade. And they’re causing the climate change.

When I look at this and see that so many millions of people who are much, much brighter than I am — far more highly trained than I am — doing their best, and it’s still going so wrong, then you have to, I believe, realize it’s a systemic problem.

Now, when we’re managing holistically — doing holistic land grazing, trying to help the government develop a policy — we begin by looking at exactly what is it that we’re managing, get that clear first, and then define the holistic context though tying people’s deepest cultural, societal values and needs to a life-supporting environment. Once we have a holistic context, and we can then look at the objectives and the actions to be taken, and see if they are in context. And that’s the way that we are able now to insure that they’re much more likely to achieve our objectives, because we’re not dealing with symptoms only, but dealing with the systematic problem and making sure our solutions don’t lead to unintended consequences.

And just as soon as governments and city folks start insisting that all policies and projects be developed holistically, you’ll see that the same people, the exact same people that are producing dismal results today will astound us. They’ve got so much knowledge. It’s just a systemic problem. And most people are good. Most people are trying to do the right thing. And just like when the Wright brothers discovered how to fly, on a certain day, we had no barriers in the way after that. A whole new society believed in technology. No government, no organization put any barriers in the way. We released human creativity, and within 70 years we were on the moon.

If you look at centuries of civilizations using agricultural practices that have culminated in climate change, it’s the same story. Now that we’ve discovered how to actually develop policies and projects holistically, if we can get the barriers out of the way, and release the creativity that’s in our universities, our farming organizations, amongst our farmers and land managers, we’ll be astounded. As I’d like to express it, the human spirit will fly.

GS: So are you optimistic about the future now? Where’s the trend going since you began?

AS: The mainstream trend is going the wrong way. I mean, you know that. But I’m more optimistic now than I ever could have been at any period in history because if we’d been having this discussion, say in the Roman times when North Africa was turning to desert, we couldn’t have done anything about it. We didn’t know what was causing it. Now we do. And even if we’d known the causes, we still were lacking the ability to communicate and network around the world. It’s the social networking that is now allowing me, for instance, to spread this to millions of people.

Now there’s one other thing that’s lacking that we haven’t quite got yet. The last thing we need is something to unite all humans. If we look throughout history, we unite in times of war against a human enemy. And we’ll unite for a long time, but the moment the war is over, we’re back to squabbling. So we need something to unite us as team humanity— something that is not a war. The only thing I could see doing that would be the overall acceptance of the seriousness of climate change. Climate change is desperately serious, but we’ve still got people deliberately causing confusion, spending millions to do that. We’ve doubters. But the moment that humans accept the seriousness of climate change, then we can unite as team humanity, whether you’re American or Chinese or African or from any other part of the world. We’re humans, and we’re not going to survive if we don’t deal with this. All the talk about adapting to climate change is like telling the frog in a slowly boiling pot of water to adapt. We have to actually address it.

GS: Well, thank you for doing more than your part to bring this to the attention to many folks. Is there something that we haven’t touched on that you would like to address?

AS: Well, I think I’ve rambled across the whole field, because this is what I live with in my mind year in and year out. I’m so worried about the future. I mean, at my age, I’m in the departure lounge. But young people are going to have to face this, and I’m desperate to give them a chance.

Read much more in the new TED Book, The Grazing Revolution: A Radical Plan to Save the Earth, available for the Kindle or Nook, as well as through the iBookstore. Or download the TED Books app to get access to this title — and the entire TED Books archive — for the duration of your subscription.

Comments (8)

Pingback: Is More Cattle Grazing the Solution to Saving Our Soil? | Iwantings|Article, media, sports, TV, conversations &more

Pingback: Is More Cattle Grazing the Solution to Saving Our Soil? | The Plate

Pingback: 8.1.14 | headmuff

Pingback: Let’s unite as Team Humanity to revive degraded land: A conversation with TED Books author Allan Savory and rancher Gail Steiger