“I am British.” Alexander Betts says this, and pauses. “Never before has the phrase ‘I am British’ elicited so much pity.”

Betts is here to talk about the June 24 Brexit vote — in which 52% of UK voters expressed their wish that their country leave the European Union. It’s a move that divided the country along almost every fault line, he says: “Everybody was blaming everybody else. People blamed the prime minister for calling the referendum in the first place. The young accused the old, the educated blamed the less well educated.” Worse, he reports seeing “levels of xenophobia and racist abuse in the streets of Britain at a level that I have never seen before in my lifetime.”

Now, one week past the shock and the meltdown, Betts asks the big question: Should we actually have been shocked by this?

The map of the UK, on the screen behind Alexander Betts, shows how the Brexit vote went down — blue to stay, and red to leave. Photo by Bret Hartman/TED.

The vote split along lines of age, education, class and geography. But Betts contends that, at bottom, the vote is about an unexamined divide: “those that embrace globalization and those that fear globalization.” He suggests that the Leave vote is a big clue that globalization — the vision of an interconnected, tolerant world, where trade, money and people are free to move — is not working for many people, and baffling to many others. This, in turn, produces fear, alienation, a sense that the country’s leadership isn’t actually speaking for them. And when globalization’s rhetoric of growth and possibility doesn’t resonate, what does, Betts says, is a populist rhetoric of nationalism and separatism, a “post-factual” politics of fear and hatred.

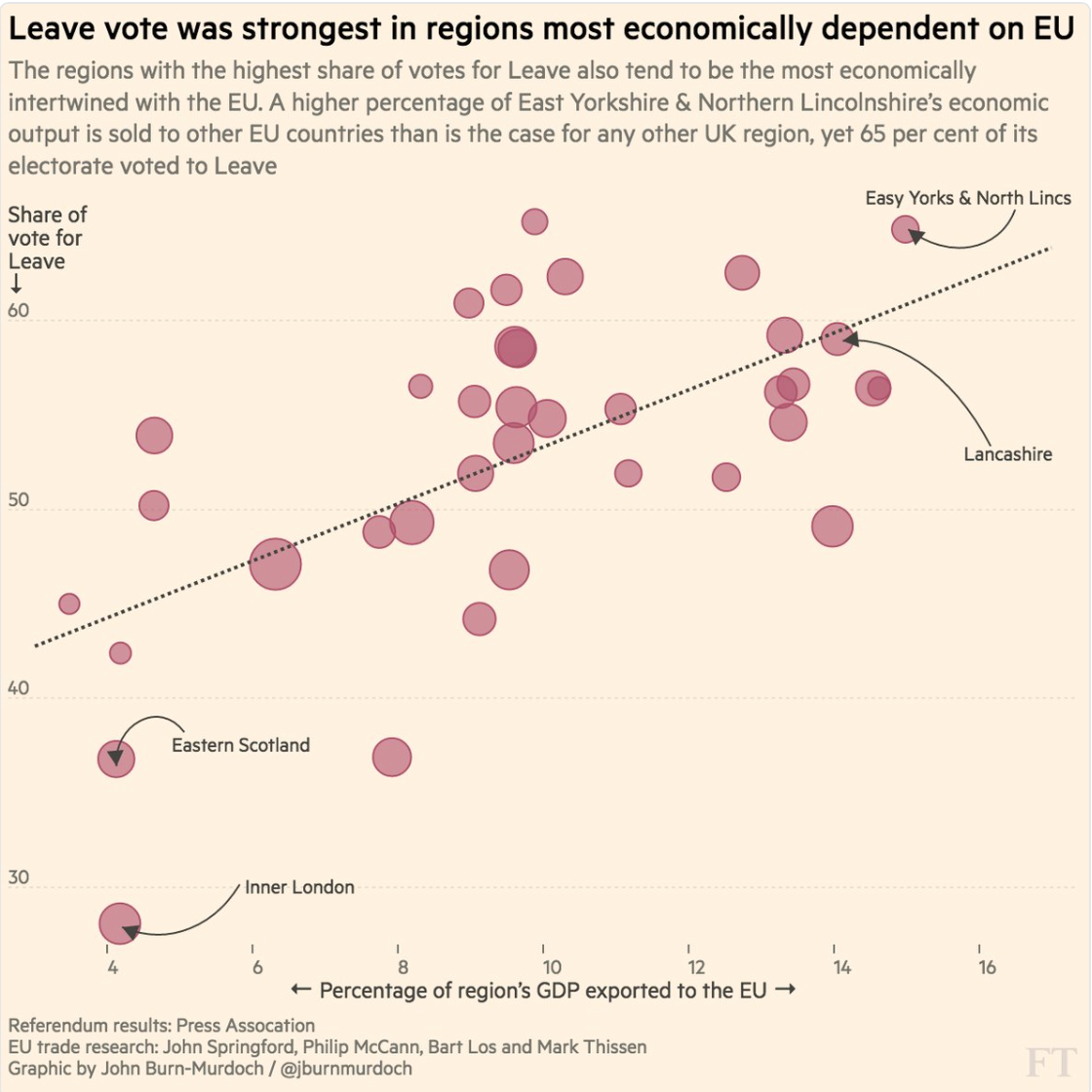

“The challenge that comes from that,” Betts says, “is that we need to find a new way to narrate globalization.” As a case in point, some of the people who voted most strongly against the EU were paradoxically those who were most dependent on EU trade (see chart below). Governments, media and elites are simply not telling the story of how they benefit.

Chart by John Burn-Murdoch.

Globalization has many positives, says Betts, but “globalization also has redistributive effects; it creates winners and losers. To take the example of migration, we know that immigration is a net positive as a whole, but that low-skilled immigration into a region can lead to a reduction of wages for the most impoverished in our society.” Balancing these effects, for instance by raising the level of social services for locals, is an important part of making globalization and immigration look less like a zero-sum game that alienates UK citizens.

So, Betts asks: “How do we address alienation while vehemently refusing to give in to xenophobia and nationalism?” He offers four steps forward.

- “How can we rebuild respect for truth and evidence into our liberal democracies? It has to start with education,” Betts says. Civic education can address the gap between perception and reality, and rebuild the space for conversation between the extremes.

- Encourage more interaction among diverse communities, addressing the “huge public misunderstandings about the levels of immigration,” he says. “Ironically, the regions of my country that are the most tolerant of immigrants have the largest stock of immigrants.”

- “We have to ensure that everybody shares in the benefits of globalization,” and that where a free trade policy creates an imbalance at the local level, it’s addressed at the local level.

- We need more responsible politics. “What we see around the world today is a tragic polarization, a failure to have dialogue between the extremes in politics,” says Betts. We might not achieve that dialogue today, but at the very least we have to call on our media and politicians to drop the language of fear and be far more tolerant of one another.”