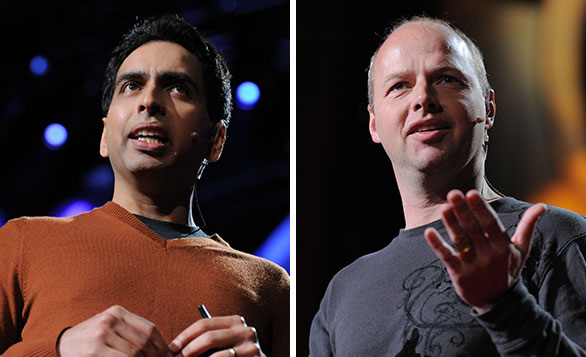

Scratch the surface of online education, and you’re destined to run into the names of two men. The first, Salman Khan, never intended to be an education icon. Instead, he simply watched with increased interest as videos he had uploaded to YouTube to help his cousin learn math were seized upon by a world apparently eager to learn via his thoughts on the subject. By making his sideline into the non-profit Khan Academy, which now offers more than 5,000 free online lessons on an array of topics, Khan has since become a central figure in the “what should we do about education?” debate.

He also inspired the second key figure. Sebastian Thrun was a computer scientist who helped build Google’s driverless car before seeing Salman Khan’s TED2011 presentation and deciding, pfft, autonomous driving was no challenge at all. Taking inspiration from Khan’s model, he resolved to do his part to redesign higher education, first via his computer science class at Stanford and now through Udacity, an organization that offers massive online courses.

TED got the pair on the phone to compare notes and discuss what both interests and worries them about the world of MOOCs and technology-inspired education. An edited version of their conversation follows. First a question for Thrun, who caused a recent ruckus when Fast Company magazine reported his announcing a pivot away from higher education toward more vocational style courses. What was up with that?

Sebastian Thrun: It wasn’t as much of a pivot as Fast Company made it look like, because we’ve been doing this for a long time. When we ask our students, ‘what excites you the most?’ they insist there’s a gap that no one really serves well: the types of skills they need know in a job, in a career, in technology, beyond what they’ve learned in their university education. A lot of it could be construed as more vocational but a lot of it is also academic and much more bleeding edge. For instance, we now have tools to do very big data analysis. So what is the most up-to-date teaching we can offer people to become effective data scientists in corporations? That’s where we get by far the largest enrolment numbers and a lot of interest from our students.

But it is the case that you’ll be moving away from focusing on academia to focusing on corporate training and executive education?

ST: No. We teach people; anyone who comes and wants to be taught is being taught. Very recently we have worked with Georgia Tech and AT&T to develop a master’s degree in computer science at a tuition cost just below $7,000 — in contrast to the regular Georgia Tech tuition cost of $45,000, and we got a record number of submissions. We have a stronger student profile than Georgia Tech normally gets for its masters students, and we’re very excited to be doing that. And we’re not moving away from that at all.

You both have very different business models for your company. Udacity is for profit; Khan Academy is non-profit. What were the decisions behind these business models — and how has that status affected how you think about your product offering?

Salman Khan: On some level, Khan Academy being a non-for-profit could be considered a little strange. It was started in the middle of Silicon Valley; I have a lot of friends who are venture capitalists and entrepreneurs, and there was some talk about it being a traditional venture-backed business. And I don’t think that there’s anything fundamentally wrong with that. But from day one, Khan Academy was never intended to be a business, so when in 2008 I started seeing it could be a real thing, I decided to set it up as a not-for-profit because I want to make sure there were never any barriers for people to access it.

I used to be an analyst at a hedge fund, and I spent a lot of time looking at companies and their capital structures and their incentives and acquisitions and thinking about what happens to companies before and after acquisitions. As the primary content creator, my motivation was to make the content. And I wanted it to be used by as many people as possible. In the for-profit world it felt like, even as a sole proprietor, if I wanted to give it away, so to speak, and have a very mission-oriented business model, what about the investors? What would happen if there were an acquisition or a change of control? In my old job, I saw many great technologies being acquired into a larger mothership and then disappear and never see the light of day.

And then on the other side, I thought about examples of institutions that have been able to stay true to their mission over multiple generations, and that’s where you look at a Stanford or a Harvard or an Oxford of the world. As you can imagine, it was delusional of me, sitting in my closet in 2007 to think in those terms, but I did a little bit. I said, ‘well, what if? We are in a new point in history, that’s obvious. But what if this crazy project I’m working on can be a new type of institution?’ And, you know, fast forward to today, it feels, at least for the direction we’re trying to go in, it feels like it was the right decision.

ST: I had come from Google, and I was inspired by a sequence of companies that offer their products for free, like Google and Facebook and YouTube. In fact, YouTube even helps you make money with your content and just takes a small rev share. And I also looked at companies in the non-profit space; the one that comes to mind immediately is Wikipedia. But I just felt it would be good to have some pressure to really think about where revenue comes from. Giving education away for free is a really good idea, but it can’t be the future of education. There has to be a business model around it that actually works. And Udacity’s model is sustainable.

Obviously, a lot of non-profits live on donations and that’s a wonderful thing. But higher education can’t exist on donations only, because if that were the case we would have a hard time paying teachers adequate salaries. I’d really love to see a business model for higher education going forward that is actually affordable, that uses modern technology to reach scale and quality and that really reimburses the services rendered in a way that’s meaningful to everybody.

So I have a question for Sal: what keeps you awake at night?

SK: Ha. Well, we’ve gotten to a point now where people are starting to know that we exist and we have real traction. Ten million students came to the site last month, and it feels like we have a voice in education now. So the thing that really keeps me up is, we’ve been given these resources, we have this soap box, this traction, how do we make sure we actively move the dial, so that ten years from now, it’s not like, ‘hey, wasn’t that Khan Academy thing cool, whatever happened to it?’ That is a scary reality for me. Mind you, just as scary is if ten years from now, Khan Academy is around, but people are like, ‘yeah, you know, Khan Academy is surviving, it’s doing its thing, but the way people learn and the ability for people to reach their potential really hasn’t changed.’

Because I think it can. It can change dramatically, and so everything I think about is how we make sure that Khan Academy actually is moving the dial. How do we make sure that we really are thinking about the learning problem in a blank slate kind of way, a first principles type of way? How do we make sure that we can be used by as many people as possible?

Another thing I do think about, and probably not to the same degree as you, Sebastian, but you know, we are primarily funded by donations right now. And that’s great and so far so good, but I would like to get to a place where, without in any way compromising our mission, without in any way compromising the access to the content, we can sustain ourselves as a not-for-profit, so all of the revenue gets reinvested in the mission.

So that’s my biggest concern. What about you, Sebastian?

ST: I should have anticipated you’d ask me the same question! I mostly stay awake at night thinking about pedagogy, about what will this digital medium end up looking like. In conventional classes, which I’ve taught for many years of my life, there’s a synchronicity constraint; you force students to progress at the same speed. When you drop synchronicity, it’s not just that you can watch videos at your own pace and repeat them. That’s version 0.01. I feel there must be a future that makes the future of learning as different as television is from radio, or film is different from a stage play. It took decades from the beginning of film to the full development of cinema. Obviously film today is different from film in the 1960s or 1980s. I’d love to shorten that. I’d love to understand — where will learning be? Will we still consume degrees? Will we make learning on demand? Will we have the power to tailor learning to individual needs, not just the speed of learning but also what we learn? How much of a difference will this make? Can we make learning truly addictive the same way we make video games addictive? If so, how do we get there?

Will we invest $100 million into a class the same way today we invest $100 million into a great movie? What would that do for the quality of education? A lot of people are arguing that the future will be somewhere in the flipped space, where you combine human services and classroom experiences with digital materials. Is that the true answer, or is there a way to deliver everything online? I think the question is still open. The biggest challenge that we face is to fully build this new medium to its potential.

SK: Do you believe education could be online only? Our sons are about the same age. I can’t imagine a world in which their schooling would be purely online. Could you?

ST: Demographics matter a lot. So when we look at young kids, I could not imagine a learning environment where they’d be sitting at home and magically they would grow up in an educated manner. But if you take the master’s degree we’re running with Georgia Tech, there the students are almost exclusively people in jobs who would have a really hard time coming to a centralized campus. In fact, the overlap between the people who applied for the on-campus degree and the online-only sessions seems to be zero, or as close to zero as you can imagine.

These are people who have different needs. They are more mature people than my six-year-old, obviously. They often already have college degrees. They need to get a certain skill set to advance their careers, and they often have a family, a mortgage, a job that they don’t want to depart from to go to an institutionalized setting We have a lot of data on this from higher education, which is fundamentally different from K-12 or pre-K. Sal, you’re in a different space than we are and are doing wonderful work in K-12. But I would not take my son and have him exclusively in the Khan Academy online. He would switch off Khan Academy and turn on Netflix or go to do something else he prefers. But as people mature more, I think they have a better sense of why they are learning, and what they want to learn.

SK: I think we’re on the same page. You know, every day, I’m learning through whatever I can find on the web or whatever resources I can find in a very independent, oftentimes very virtual way. So yeah, I think you’re absolutely right. It’s a complete spectrum. At the younger age range, it’s hard to imagine education without a significant physical socialization component. With adults, it could be gravy if the person has the luxury to do it, but I agree with you, I could completely see a working person getting tons of value, perhaps even more value, if they’re studying while they’re working or while they have their other life.

ST: I have this very deep belief that for this specific group of people, online would be significantly better than what you could do in the classroom. The average age of the people who applied to our and Georgia Tech’s online master’s degree was 11 years older than the same group applying to a physical on-campus degree, and I think that speaks for itself. These are people who are further progressed in life, who are learning for their own benefit, but they also have constraints that make online-specific classes suitable for their lifestyle. In our classes, people self-organize and create sometimes hundreds of physical meet-ups per class. There’s certainly a strong desire to have that kind of interaction. But over the last ten years, we’ve also learned that meaningful social relationships, including finding your life partner, can take place online. There’s a lot to be learned about how digital media, the ability to reach anybody any time, really transforms the peer interaction experience in education at large.

Would either of you hire somebody whose education came solely from online classes or MOOCs?

SK: If you’re talking about the skills that we’re hiring for, the stuff that’s typically learned in college or graduate school, then absolutely. In fact, we already have. We recently hired two people and we didn’t even know what their degrees were, if they even had degrees. We hired them because of the work they did on the computer science platform on Khan Academy.

ST: Yes, the same is true here. And we go around companies and ask that same question, especially in startup-land, and we very frequently hear that the attention that’s being paid to degrees is being diminished. That is, more and more people are being hired on their work samples, on the projects they’ve done, the type of portfolios they’ve developed, and that’s something that’s very easy for Udacity students. And we hired a whole bunch of people ourselves from our network, completely oblivious to their degree but based on their ability to solve problems and socially interact with other people in our discussion forums. One of our main hiring funnels has become our own network of our own students.

Now, I should say, the MOOC movement has often been pitched as “MOOCs against college.” And I don’t think that’s a fair perspective. I don’t think the Salman Khan movement is a “movement against K-12,” and I don’t hear Sal saying he’d like to replace K-12. I don’t think it would be even feasible to think of MOOCs as a replacement for college. I think of them more as an augmentation. I think there’s a lifelong learning need, specifically for people who work in a fast-moving industry such as technology, to just stay up to date. What we find in general is that the certificates that we give people, when we talk to employers, carry a lot of weight, because they really relate to the types of skills you need to have to be successful in the field. Over 50% of our students already have an advanced degree, and they really want to empower themselves to do a certain type of job that they couldn’t have done otherwise, and getting a second degree might just not be feasible, given the cost and the requirements. With our Udacity MOOCs, learning now takes place throughout life on demand, when you need it. You can go and very quickly learn a skill that you need.

It seems like both of you have been subject to quite a lot of criticism about your respective programs over the years. How do you handle that?

SK: Well, one of the great things about online education is it’s out there for everyone to see, and it’s out there for everyone to critique, both constructively and maybe sometimes unconstructively. And that’s what’s only going to make it better. Here at Khan Academy, we like it when people point out our weaknesses, because that’s something that we can improve on. I think most of the criticism, though, has been more about the misunderstanding of what we are and what we’re trying to be. We aren’t about replacing physical schools. This is about allowing physical schools to become more valuable, to move up the value chain. It’s about the idea that if lectures can happen in the students’ own time and pace then you can do a higher order activity in the classroom: more conversation, more problem solving, more projects. You can start thinking about allowing students to learn at their own pace, or have them work in a multi-age classroom, focusing more on creative things like projects. When people start to understand that, and when they realize that we’re investing heavily in tools for teachers because we view teachers as a super-important part of this ecosystem, that’s where we get a lot of very positive feedback from teachers everywhere.

We’ve also been the beneficiary of some very, shall we say, grand headlines. You know, ‘the future of education,’ and whatever else. And I think people quite rightly say this isn’t that simple of a problem, it’s not going to be solved overnight and there is no silver bullet. And we agree. It’s not like you can just air-drop Khan Academy or the computer into a school and all of a sudden the flowers will bloom and the butterflies will start flying.

ST: Just like Sal, we love constructive criticism. In the very early days, I taught a course on statistics and a teacher on the east coast wrote a really negative, anonymous review that was many pages long. It was devastating to read that almost every aspect of my course was mistaken, but there was an enormous amount of great information in there. So we found out who it was, we contacted the individual and had a very positive conversation afterwards. And he really helped me to improve the course.

It’s also so transparent now. We do a lot of internal data analysis on how good our courses are. Our students give us feedback, actively by commenting on things or passively by skipping things or rewinding things or getting quizzes wrong. We use that data to improve the course experience. That’s a unique thing you can do online. For any A/B test we run, we can get an answer within 24 hours. That to me is a great opportunity for the future of education, because now we can use data-driven analytics to understand how education works best, not just the innate skill of the teacher.

As for recent criticism, it’s always interesting to see who critiques. There is a lot of misunderstanding about existing faculty members, and it’s been fueled by what I would consider hype. For instance Thomas Friedman went out to proclaim MOOCs as the future of higher education. It was really not understood well that it is a process to find a good formula. I really believe that we have to work hard to make online education better and better, and eventually it’s going to be really great. But like most of these things, it takes time to improve, to understand and to make things really good. At Udacity, we always strive to make things better and learn from our mistakes. I think that was not fully understood by some of the most ardent critics.

There is something of a difference in the structure of your classes. Khan Academy gauges where the student is and then recommends the next class depending on how they’ve done; the Udacity model is more about offering set courses with a syllabus set by a teacher. Sebastian, would you like Udacity to move to a more personalized, networked type of education programming?

ST: We actually find that our students personalize their education much more than it might seem. They quite selectively access specific content and quite selectively do background readings. About half of our students skip over massive amounts of content along the way to reach a certain goal. I think the beauty of Khan Academy, Udacity and the many other entities out there is that we’re in an age of experimentation, where we have different players putting money, so to speak, on different hypotheses, to see what the outcome is.

I very carefully observe what’s happening in the world, including at Khan Academy, to really understand how student learning best takes place. We started out with an artificial intelligence course that happened to be a course at Stanford and, to my surprise, it unleashed public attention at a level that I’d never anticipated. But actually we’ve been undoing a lot of the things we did in that AI course. We undid the fact that this was a fixed time course with fixed deadlines into an open course you can take at your own pace. Now we let people go to their own beat and skip stuff along their own way.

So we read a story, Sebastian, where you said you were inspired to start Udacity as a result of seeing Sal’s TED Talk in 2011. Is that true?

ST: I vividly remember the exact chair on which I sat in the audience. There are few moments in my life where I really remember what I was doing. I never made a secret of my admiration for Sal. But it really struck me for something as fundamental as education, that society had really neglected the idea of exploration and trying new ways of reaching more people, and Sal stood out as an individual who was doing something absolutely amazing, which to him didn’t even feel amazing. He just recorded a few videos and that’s how it began, but all of a sudden, tens of millions of students’ lives are materially impacted and changed for the better through his work. That was the moment it became clear I couldn’t face my Stanford students the same way I did before. Now I want to say, I totally respect people who teach physical classes, but for myself, this became a moment when I felt, we had to give education-at-scale a try and see what happens.

SK: Whenever I hear that I actually don’t know if he’s serious or not — because the love is two ways. Sebastian has always been a bit of a superhero for me, he’s obviously Mr. Self-Driving Car and everything else, one of the leaders in computer science, so when I found out that he even knew who I was… Yeah, it’s always a little surprising to know that I might have influenced him in some way.

Aw.

“Questions Worth Asking” is a new editorial series from TED in which we pose thorny questions to those with a thoughtful, relevant (or irrelevant but still interesting) take. This week we’re asking, “What’s next for MOOCs?” See also a primer to catch you up on all things MOOC as well as a Q&A with edX president, Anant Agarwal.

Comments (36)

Pingback: Online Learning and the Future of Education - The Empowering Artist

Pingback: Online Education: Thrun & Khan | MtRtMk

Pingback: Два гиганта онлайн-обучения обсуждают будущее образования | Лови Момент!

Pingback: How does your typical provost think? | More or Less Bunk

Pingback: Sebastian Thrun and Salman Khan Talk Online Education - Tunapanda

Pingback: SCH CONSULTING – When Hiring, Udacity Certificate Is Good Enough for Udacity

Pingback: When Hiring, Udacity Certificate Is Good Enough for Udacity | My Web Marketing Planner Blog

Pingback: When Hiring, Udacity Certificate Is Good Enough for Udacity - Advanced Computer Learning Company

Pingback: Online lecturing – an appropriate learning tool in online education? | Education for Sustainable Development

Pingback: In conversation: Sebastian Thrun and Salman Khan talk online education | TED Blog | NLG Consulting

Pingback: Daily Bullets: Is Marcus Smart’s draft stock falling? | Pistols Firing

Pingback: Two giants of online learning discuss the future of education | EduWire.com

Pingback: MOOCs and the Future of Education with Sebastian Thrun & Salman Khan | Learning^2

Pingback: In conversation: Sebastian Thrun and Salman Khan talk online education | TED Blog | LaAntiguaFrontera

Pingback: TED News in Brief: JR’s art dances, this world might be a simulation and … Lean In, The Movie?

Pingback: TED News in Brief: JR’s art dances, this world might be a simulation and … Lean In, The Movie? | jr