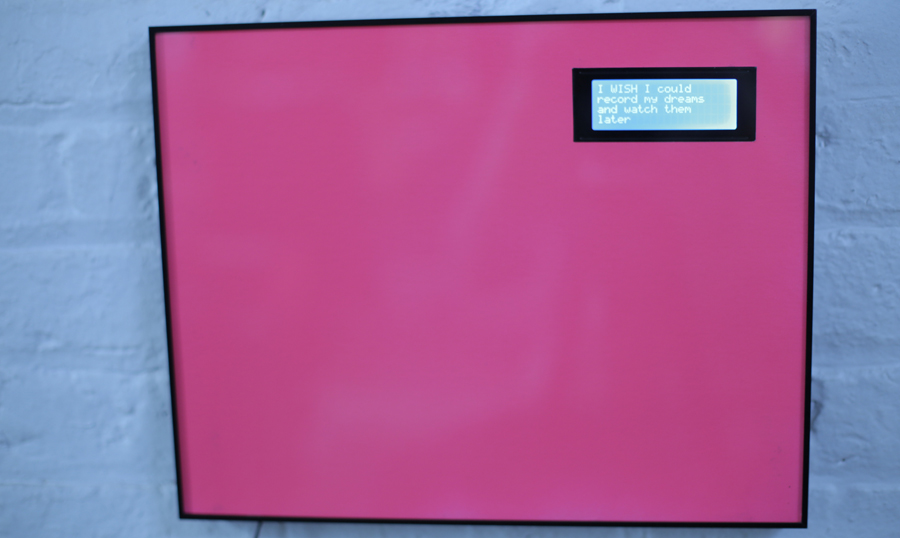

Jean-Baptiste Michel’s “I wish I could be exactly what you’re looking for” (2014). The words that appear in it are tweets that start with “I wish.” Photo: Courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Michel

Jean-Baptiste Michel has sold a small sculpture to the Whitney Museum of American Art. A major museum acquiring a piece—that’s a big moment for any artist. But this sculpture is the very first piece of art Michel ever created.

Jean-Baptiste Michel + Erez Lieberman Aiden: What we learned from 5 million books

Michel is the data researcher who showed what you can learn using Google’s Ngram Viewer at TEDxBoston in 2011, and who calculated the mathematics of history at TED2012. He credits one thing with inspiring him to take his love of data and turn it into art: joining the TED Fellows program.

Jean-Baptiste Michel + Erez Lieberman Aiden: What we learned from 5 million books

Michel is the data researcher who showed what you can learn using Google’s Ngram Viewer at TEDxBoston in 2011, and who calculated the mathematics of history at TED2012. He credits one thing with inspiring him to take his love of data and turn it into art: joining the TED Fellows program.

“I’m not an artist. I never thought that I could do anything in that area,” says Michel, in the Brooklyn office space he shares with several other TED Fellows. “I really consider this a very direct consequence of my being a TED Fellow because I was not exposed to this kind of world before—I was in dry academia. The ability to just bring to life the other aspects of our creativity is something [I learned from] seeing what the Fellows were doing, and understanding their very down-to-earth, no-fuss approach to doing things. Just trying stuff and seeing if it works.”

The 10×15 sculpture acquired by the Whitney at first looks like a shiny square of hot pink lacquer. In the corner is a small screen, which flashes with sentences like, “I WISH I could record my dreams and watch them later” and “I WISH you could delete feelings.” These sentences are real-life tweets, starting with the words “I wish,” posted by people around the world. Michel says there are several thousand of these tweets every minute—a Raspberry Pi behind the display selects a small group every 30 seconds, and changes which ones are shown every five. Michel named the piece “I wish I could be exactly what you’re looking for,” after one of his favorite tweets it has displayed.

The idea behind the piece is to take a set of big data—all the tweets containing these words—and to create an intimate connection with its smallest pieces. “I was not expecting that [the tweets] would be so meaningful. It’s actual emotions, people’s inner desires on display,” says Michel. “What I was used to looking at before was the breadth—it’s big data, so you measure volumes, and what you see is patterns … What I was interested in here was the contrary—going back to that individual thing that this pattern came from. I wanted to show the original intent, the original thought itself.”

Michel got the idea for how to achieve this goal after seeing others in his office playing with Arduino and Raspberry Pi.

Massimo Banzi: How Arduino is open-sourcing imagination

But creating a beautiful object—one embedded with electronics—was very new to him. Many people in his office space lent a hand to help him clarify the idea, order the right materials and figure out how to use tools. TED Fellow James Patten was especially helpful on all these fronts.

Massimo Banzi: How Arduino is open-sourcing imagination

But creating a beautiful object—one embedded with electronics—was very new to him. Many people in his office space lent a hand to help him clarify the idea, order the right materials and figure out how to use tools. TED Fellow James Patten was especially helpful on all these fronts.

Excited by what he saw developing, Michel created several other pieces in line with the first: “I want to be your idea of perfect” (which displays on a long, thin screen akin to a stock ticker) and “I need to go away for a while” (set into a block of wood). Just last week, Michel made his newest piece, called “It’s time to try defying gravity,” which he built inside a vintage flip clock. As Michel walks by his desk, the piece displays the words, “IT’S TIME for another tattoo.”

Michel, who recently published the book Uncharted and is focusing on a new venture Quantified Labs, typically only displays his art at home and in his office. It was another TED connection that led to the Whitney purchasing “I wish I could be exactly what you’re looking for.” One day, Marc Azoulay—studio director for TED Prize winner JR—came by Michel’s apartment, and gravitated toward the piece. He suggested that Michel display it as part of his exhibit exploring the interplay between public and private at the SPRING/BREAK Art Show in New York. It was there that a curator at the Whitney saw the sculpture and brought it to the museum’s buying committee.

Last week, Michel visited the Whitney to make sure all parts of the piece were working properly. “This continues to baffle me day in and day out,” he says. “This is the first piece that I made—I’m just still very surprised. It’s extremely lucky.”

Jean-Baptiste Michel’s latest work, “It’s time to try defying gravity” (2014), which he built into a vintage clock. Photo: Courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Michel

A closer look at “I wish I could be exactly what you’re looking for” (2014). Photo: Courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Michel

Another in the series, called “I need to go away for a while” (2014). Photo: Courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Michel

Comments (5)

Pingback: Не успел исследователь данных Жан Батист Мишель создать свое первое произведение искусства, как его тут же приобрел Музей Уитни | TED RUS

Pingback: Assignment 1 | j term: nature of code