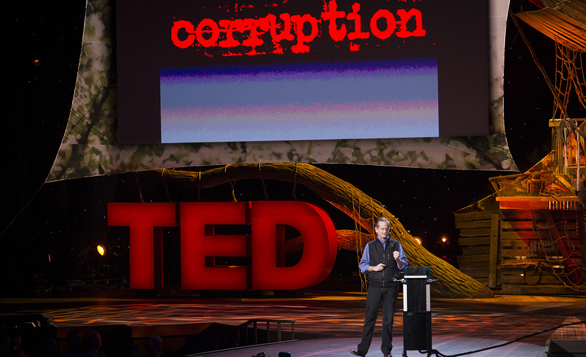

At TED2013, Larry Lessig used a bold word to describe the American electoral system: a corruption. Here, he explains why more people are starting to use this terminology. Photo: James Duncan Davidson

Larry Lessig is about to complete a 185-mile walk across the state of New Hampshire. He began this journey on January 11 and has walked despite rain, sleet, snow, ice and freezing cold, as the temperature in this state ranges anywhere from the lower thirties to the negative teens in the month of January.

Lawrence Lessig: We the People, and the Republic we must reclaim

Lessig undertook this walk to hammer home the idea he presented on the TED2013 stage: that the American electoral system is inherently corrupt, giving outrageous influence to the very small percentage of people who give money to political campaigns. But Lessig’s idea is even bigger than that: he believes this system can change.

Lawrence Lessig: We the People, and the Republic we must reclaim

Lessig undertook this walk to hammer home the idea he presented on the TED2013 stage: that the American electoral system is inherently corrupt, giving outrageous influence to the very small percentage of people who give money to political campaigns. But Lessig’s idea is even bigger than that: he believes this system can change.

For Lessig, the key is demanding it. This walk, which Lessig’s organization Rootstrikers dubbed the New Hampshire Rebellion, focused on asking the residents of New Hampshire to make candidates in the 2016 presidential primary answer the question, “How will you end this system of corruption?” Because New Hampshire is the very first primary — one that the entire country watches with bated breath — these residents are the most able to apply actual pressure with just a few simple words.

The final walk of the New Hampshire Rebellion began today at noon, and it concludes on this day for a specific reason: today is the birthday of Doris “Granny D” Haddock, an activist from the state who, at the age of 88, walked across the country advocating for campaign finance reform. Lessig sees his message in step with hers.

Lessig called up the TED Blog when the group was just six miles away from the end of the road. Here, an edited transcript of that conversation.

Where did the idea for this walk come from?

We’ve been thinking for a while about how to make this issue a focus of the 2016 presidential primary. We wanted to come in and talk in New Hampshire to try to get people to put this question at the top of the list that they ask presidential candidates. But we wanted to think of something that would be more dramatic to introduce the idea. The fact that, 15 years ago, Granny D walked across the United States seemed like a perfect link to get people to think about this issue here. This is the most important primary. It’s the first. It’s a small state, so it’s possible that you could recruit enough people here to make this a critical issue, and thereby change the way the debate in 2016 presidential primary happens. That’s our objective.

What is it about joining a physical action — a difficult journey — with an issue? Why do you think that’s such a powerful combination?

I think it’s powerful both for the audience and for the participants. It’s powerful for us, because some days, when we were walking 21 miles, it really hurt. It was physically difficult — and that kind of drives your commitment in a way that’s productive. It makes it a much more committed team. And for the audience too, I think that they see it and they recognize the difficulty of walking through New Hampshire in January, so they’re more likely to watch and listen or try to understand why we’re doing it than they would be if we just had an ad on a webpage. It’s a way of communicating that’s more authentic and therefore more effective. That’s something I never would have thought about before we did it, but I’m now absolutely convinced of it.

How have you dealt with the cold and the snow?

There was only one really bad day — the first day was pouring rain, and things got very wet and cold, and I think many of us thought maybe this wasn’t such a great idea. But ever since, even if it’s cold, you’re walking — so you pretty quickly you get warmed up. Some days the wind chill has been below zero, but you just have to cover your face. People have borne up pretty well.

One of the beautiful snowy forests that Lessig describes below. Photo: Bruce Skarin/Flickr

Who have you found yourself talking to along the way?

I’ve been inspired by the incredible response on the street. People constantly honking as they drive by. We’d walk down the street, and people’d come out of their houses and wave at us. When we go into stores, people come up and talk to us. It’s been really, really encouraging that people are engaged and trying to connect with us. [Before we left], we did a poll that found that 96% of Americans believe the influence of money on politics is important, and that the influence of moneyed politics should be reduced. And so, I did this shtick of: “I’ve come looking for the 4%.” There was one state trooper who was inspecting some ice fishermen on a frozen lake who I asked this to, and he kind of looked at me like I was a Martian and said, “Hell no. Nobody up here thinks that!”

Have you found any members of the 4%?

I haven’t, no.

In your talk at TED2013, you laid out the parable of Lesterland and now you’re doing this walk. How do you think of creative ways to connect to people on this topic that, yes, they care about — but they’re so used to inaction on?

In that same poll that we found 96% of people thought it important to reduce the influence of money, we also found that 91% thought it would never happen. Couldn’t be done. Those two numbers together, I think, explain the resignation and the fact that it’s so difficult to get people to engage about the issue. So it means the challenge — the objective — has just got to be to give people some reason to have hope. That’s the thing that we are trying to play out here. We’re trying to show people the structure of a plan that could actually make this a salient issue in the next presidential election. And if it is, possibly the next president would be someone committed to making this reform real. It’s not about not convincing people there’s a problem — everybody sees that. It’s not convincing them about the source of the problem — they also see that. It’s about convincing them that there’s a way to solve it. And if we do, then we can unleash that pent-up, frustrated desire to solve this.

The talk has been viewed so many times, I feel like everywhere I go, people know what it’s about and have seen it. The thing that that talk got me to crystallize — and I’ve continued to refine it — is the way in which we’ve basically become disenfranchised in our own election system, because the money election, which is so critically important, is so restricted to such a tiny proportion of Americans. The rest of us are left to the general election after some of the most important decisions have already been made. That story, as it continues to develop and resonate, is incredibly effective in getting people to understand why this has got to be reformed.

You mentioned hope. Have you seen any glimmers of hope since you gave your talk?

Yeah. The fact that this has become so prominent and salient as an issue means that politicians are going to begin responding to it. We’ve begun to see great legislative proposals. John Sarbanes has Grassroots Democracy Act that would radically change the way campaigns are funded. That’s incredibly important progress. I think that what’s important now, though, is building a strong enough outside-the-beltway movement to force them to do something about it.

It’s interesting: There’s been increasing number of beltway politicians willing to use the word “corruption” as describing what the current system is. John Kerry’s closing speech to the floor of the Senate explicitly called the system out as a corruption. I’ve seen more and more congresspeople who are willing to call it a system of corruption. We have this event up here in Concord where John Sarbanes spoke, and he was quite explicit about this as a system of corruption. Carol Shea-Porter is one of the two Representatives from New Hampshire, she too was talking about this as a system of corruption. That’s striking, because two or three years ago, I gave a talk in front of the Democratic Caucus, and called it corruption, and they were very angry with me. I said, “It’s not that you’re corrupt, it’s the system that’s corrupt.” But that subtlety is not something that goes over well. But increasingly, this is just the way it’s being described. That’s what necessary, I think, because it’s only when people see it like that that we develop the right kind of movement to do something about it.

Have you found along this walk that authorities have been helpful or discouraging?

The authorities have been great. The police in particular have been really great because there’s no one here who supports this system. The only beneficiaries of this system are lobbyists and the interests they represent, and those aren’t the average people in New Hampshire. Which is why this is such a great state to make this push.

What’s one of the most beautiful places you’ve seen on the walk?

This is a stunningly beautiful state. Up in the north in particular, we would go through these long stretches of woods and — when the snow came down — the snow-powdered woods were just incredibly beautiful. And as you get south, to the cities, then it feels more like you’re back in civilization but there are long stretches where we were out in the middle of nowhere in the most beautiful part of the country.

How many people have been with you along the way?

We’ve had about 17 who’ve been through-walkers, who’ve done the whole way. But then there are day walkers who join on particular days. Some days we’ve had over 50 people walking — which actually is more than we should have had. It’s just dangerous and difficult to do with that many people. But fortunately, everything worked out.

What has the march sounded like?

We had a march song, which we sang a bunch of days, but mainly people are just talking to each other. Sometimes when we have to walk single-file because of the roads, it’s just thinking or listening to books on tape or to music.

What about signage?

There’s a bunch of different signs. We encourage people to make their own. We have a couple that are New Hampshire Rebellion signs, but we really wanted them to be more authentic. Some people have made signs about the issue of campaign finance reform or transparency. We have one guy who actually is an artist and he painted an image of Granny D, and then below it says, “Live free.”

A large gathering of New Hampshire Rebellion walkers. Photo: Bettina Neuefeind/Flickr

How does it feel to be just six miles from the end?

You know, I’ve loved the walk. I mean, I’m going to be happy to get back to my family — but I’m not sure how I’m going to feel when it’s over.

It’s funny, we recently had a talk from Diana Nyad, who talked about her historic swim from Cuba to Florida, and she said that she got to the 15-mile-left mark — she felt a real sadness that the epic was over. How would you like to end this walk?

We’re going to end it with a party honoring Granny D’s birth. She was born on the 24th, so there’s a big party in Nashua to celebrate.

What do you think has been the biggest thing you’ve learned along this walk?

I think the most important lesson is just how passionate people are about this issue. Most politicians don’t notice that, because the pundits and experts tell them this is not an issue people care about. So they don’t talk about it. We’ve connected with people, and given them a sense that maybe there is something to be done about it. The kind of urgency that they’ve had has been really encouraging. I’ve been surprised by it, because I’ve never put myself in a position like this, to have to confront it. It’s been incredible to see the reaction.

Any thoughts started crystallizing about what your next action is?

We’re going to continue to build out this project to deliver on the objective of making sure that every presidential candidate gets asked this question every single time they speak. And so, building the infrastructure to make that possible is the next task. That’s what we’ll be working on.

Comments (10)

Pingback: Why Citizen-Funded, Independent Campaigns Are Important Now | IVN.us

Pingback: Kevin Kelly: Reversing A Corporate Coup D'état

Pingback: This Man Just Walked 185 Miles Across Freezing New Hampshire: Here’s Why

Pingback: 185 Miles of Empowerment: Walking the NH Rebellion | IVN.us