When it comes to time, there is the past, the present and the future. But during day four of TEDGlobal, speakers seemed especially concerned with the former and the latter.

Kicking off session 11, the first of day four, art diagnostician Maurizio Seracini shared his 30-year quest to find Leonardo da Vinci’s missing fresco “The Battle of Anghiari.” Seracini—the only real-life person mentioned in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code—spoke about the exciting process of excavating art and finding “faces no one has seen for five centuries.” He showed how his team is rendering layers underneath art visible again through an app that runs on tablets, which allows museumgoers to rub the image of a painting in front of them and see what’s beneath the surface.

Later in the session, called “Taking Another Look,” data commons advocate John Wilbanks imagined another way to look beneath the surface, by opening up medical data to drive new discoveries. Policies surrounding informed consent of medical research subjects have not changed since World War II, which has made it impossible for mathematicians and scientists to share health-related data and create sample sizes large enough for conclusive inquiry. Wilbanks imagines a database where, in the future, more than a million participants will give blanket consent for their medical and lifestyle data to be shared and studied.

“Cancer sucks, and, when you have it, you don’t have a lot of privacy in the hospital. You’re naked,” said Wilbanks. “Being naked and alone can be terrifying … but being naked in a group can be quite beautiful.”

Another snippet of the future in session 11: artist Imogen Heap, who gave a beautiful demo of her next-generation music-making gloves.

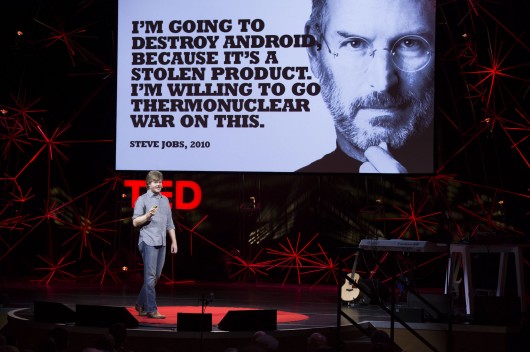

In session 12, filmmaker Kirby Ferguson looked back to the past, making the bold statement that “everything is a remix.” Ferguson pointed to Bob Dylan, who widely mined the musicians who came before him for ideas. Ferguson even let some famous innovators make his case for him, recalling Henry Ford’s words “I simply assembled the discoveries of other men” and referencing Steve Jobs quoting Picasso’s famous line, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

Soon after, management expert Margaret Heffernan shot back to the 1950s, telling the story of ahead-of-her-time epidemiologist Alice Stewart, who realized that childhood cancer was developing as a result of prenatal x-rays. It was a shocking finding that challenged the thinking of the medical establishment — which promptly ignored her, and kept on giving deadly x-rays for two and a half decades until the practice was banned in the ’70s. How did she remain confident over those years? She worked with a statistician who actively tried to disprove her work. His job was “to prove Dr. Stewart wrong.” And he couldn’t.

“It’s a fantastic model of collaboration: thinking partners who aren’t echo chambers,” Heffernan said. She calls on managers to use dissent as a tool for getting the best creative work from their employees. “We have to see conflict as thinking, and then get really good at it.”

Closing the conference, social media theorist Clay Shirky gave a riveting talk about how innovations in organizing the chaos of open-source coding could, in the future, help create democracies where everyday citizens participate. Shirky fused his idea for the future with an example from the past.

“Whenever someone says that something on the internet will change society, you hear this: ‘The thing with the singing cats?” Shirky said. “It didn’t take long after the invention of the printing press for someone to think that erotic novels were a good idea. It took another 150 years to think of the scientific journal.”

Like Seracini, Ferguson and Heffernan, throughout this week’s TEDGlobal conference, speakers reached to the past for lessons about humanity. In session 3, author Karen Thompson Walker spoke about our tendency to fear scenarios that are less plausible but more terrifying. Her example: the whaleship Essex, whose shipwrecked crew preferred to starve at sea rather than land on islands they believed to populated by cannibals. In session 10, historian Laura Snyder pointed to the 1812 “Philosophical Breakfast Club” of Charles Babbage, John Herschel, Richard Jones and William Whewell, which created some of the most basic principles of modern scientific inquiry. The point: science doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and cooperation propels us forward.

Like Wilbanks and Shirky, a large number of TEDGlobal speakers imagined the future and advances we might see in it. In session 1, data intelligence officer Shyam Sankar spoke on one of the most futuristic topics possible—the symbiosis between humans and robots. Sankar stressed that while machines are good at calculating, humans are far better at interpreting. He concluded, “Instead of thinking how the computer can solve the problem, design the process around what the human can do with it.”

The next day, in session 5, artist Neil Harbisson took the idea to the next level, calling himself a “cyborg.” Harbisson is color-blind and uses an electronic eye to deliver colors to his brain as sounds. “When I started to dream in color, I felt the software and my brain had united,” he said, in an evocative presentation that introduced attendees to the color of music and the sound of purple.

TEDGlobal 2012 explored the theme of “Radical Openness”—what happens when those in power release information, when crowd-sourcing is a strategy, when creativity goes collaborative, and when technology is pushed in new directions. So what now? That’s up to all of us.

As Heffernan put it in her talk today, “Openness isn’t the end. It’s the beginning.”

Comments (2)