TED Fellow Erine Gray founded the website Aunt Bertha to help people find social services in their area, quickly and easily. The site was inspired by his own struggle to find help for his mother, who needed special care.

Most of us will, at some point, face a life crisis — divorce, job loss, illness, eviction. In the United States, 95% of social safety nets are provided by charity organizations and NGOs, so finding help in a crisis situation can be confusing and distressing. Erine Gray is the founder of Aunt Bertha, a free-to-use online platform that makes it easy for anyone in the US to find and apply for social services — anything from Medicare to food stamps to housing — just by typing in a ZIP code. Aunt Bertha serves people in all 50 states, with in-depth coverage in Texas, Colorado, Central Florida, and Richmond, Virginia. Starting this week, Aunt Bertha has added New York City to its in-depth coverage list. We took this moment to talk to Gray about how Aunt Bertha was born, how it works and how it’s shaping up to be a valuable tool not just for families and individuals in need but for policy makers, advocates and community workers as well.

Aunt Bertha started as a response to an illness in your own family. Can you tell us about your experience?

I grew up in a small town called Olean, New York, an hour south of Buffalo. When I was almost 17, in the summer of 1992, my mom, who worked as a janitor at the community college at the time, caught a rare disease called encephalitis. She needed to be rushed to Sayre, Pennsylvania, which was a four-hour drive. She flatlined twice on the way there, but made it to see a brain specialist. She went into a coma and survived, but she suffered brain damage. Her memory was essentially wiped out — everything after her childhood and the first few years of the birth of her first daughter was gone. She had no memory of me and my little sister.

She was released from the hospital three months later. It was me and my dad and my sister, just trying to figure out how to take care of her. Obviously you don’t get a certification for these types of things. Nobody is ever really prepared. She recovered, to some extent, but she suffered from seizures on a regular basis—they would sometimes knock her out for the day. My dad did the best he could to take care of her, and he did, for nine years. He did it alone for the most part. We didn’t know what services were available. And when we did find programs, it was difficult to get through the application process.

I went off to college, studied computer science, but ended up getting my degree from Indiana University in economics. I was working as a contractor in Austin, Texas, when I got a call from my dad. He needed help. My mother was getting older and started to have early-onset dementia. I flew up to New York and packed her things, and moved her to Texas, and became her legal guardian. So there I was—unprepared—trying to figure out how to navigate a system for somebody who needed help.

What kinds of services are available with people in this position?

Unfortunately there are not a lot of resources available for older adults with mental illness in the US. There are private care facilities, but these are financially unattainable for many. All too often, people either end up in the prison systems, homeless or, if they’re lucky—in a nursing home.

I went through a long process of looking for a nursing home, but many of them discriminated against people with signs of mental illness. If you think about it from their perspective, they don’t want people who might want to run away, or people who are difficult to deal with. We must have been rejected by 15 to 20 nursing homes. I had a social worker give me advice on how to find a place that would take her. She told me to dress up, wear a jacket and go meet the administrators in person. I’d be invited to submit an application—but the only response I would get would be very concise rejection letters that said, “We can’t meet your mother’s needs.” It seemed at the time to be a legal form of discrimination.

Erine Gray says that the frustrating experience of trying to find social services for his mom helped him identify an incredible need: an easy-to-use searchable database of services in a specific area. Photo: Courtesy of Erine Gray

It was navigating this system for somebody who’s disabled that made me see how broken the system really is. So I went back to graduate school and got my masters in public policy from the LBJ School of Public Affairs here in Austin. I ended up working as a contractor for the state of Texas, essentially looking at improving the way people find out about social service programs like food stamps, the food subsidy program in the US, Medicaid, the US welfare program and how they apply for them. The company I worked for also ran a call center that helped people get enrolled into these programs.

During those four years, 2006 to 2010, there was a big economic downturn. Texas is the second largest state in the US—a huge, huge economy . Enrollment levels grew significantly, but the state didn’t have the capacity to deal with that much growth. So it was a challenge to figure out how to get everyone connected with what they needed. On most nights, my car was the last car in the parking lot. I’d analyze calls, and realized a lot of people were ringing just to say, “Hey, did you receive my application for food stamps?” “Or I sent you a fax, can you confirm you got it?” We figured out pretty quickly that this information was stored in the system, so our team redesigned the menu, allowing much more self-service. This meant people in need could get answers in 30 seconds rather than having to wait on hold for 30 minutes.

We worked on several big projects like this that made things more efficient. The number of calls and the amount of time spent taking them went down. These efforts helped turn the project into an operation that could scale.

It was this work, as well as my family’s experience caring for my mother, that led to the idea for Aunt Bertha. I thought to myself, “Well, if we can visualize data for complex programs like the food stamps program, would more self-service options in social services be cheaper to implement and less frustrating for the person in need?” And that was the a-ha moment—the big idea.

So how does it work, from perspective of the user? I’m assuming that searches are anonymous, first of all?

Yes. People search for all sorts of things—like HIV testing services, survivors of incest support groups—and we wanted our search to be completely anonymous.

Here’s how it works. For any ZIP code in the United States, you’ll see at least 200 listings. Some areas have more programs than others, but we are rapidly expanding. So say you’re in Austin. You type in a ZIP code, and in a couple of seconds, it’s pulling in all of the national programs, state programs, county programs, city programs, and then programs that cover just your neighborhood.

If you type in “food pantry,” it pulls in the food pantry programs, organized by how close they are to you. You can filter for other variables—say “seniors.” As you drill in, you get the hours and location, and so on. You can also search by eligibility: put in a family size—let’s say I have two kids under 5 and I make $700 a month. What comes up is the Texas Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—SNAP—what used to be called food stamps. I know, based on publicly available rules, that a family of this makeup would likely get somewhere around $458 a month in benefits.

What do you need help with? A sampling of what people search for on Aunt Bertha. Image: Aunt Bertha

Or maybe you’re prescribed a prescription drug—say Prozac. You’re uninsured and you don’t have the money for it. It will bring up the Lilly Cares program. Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of Prozac, will give it to you for free if you apply.

With an integrated application form we built, the seeker can log into Aunt Bertha and fill out the agency’s form in just a few clicks. The system saves the information so that if you apply to anything else in the future, any redundant questions get filled in automatically. You can also upload any supporting documentation. A dashboard shows all the programs you’ve applied to, the application’s current status, and a history of interactions with that agency. This eases phone traffic. The agency can see the same application from their perspective, and process it from there.

One cool thing about our approach is that we kept rural America in mind. There are hundreds of organizations that serve these areas remotely, through call centers.

Is search data used for anything else?

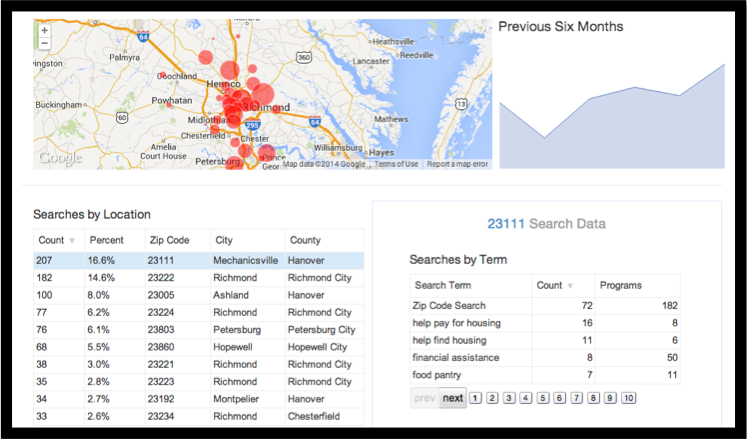

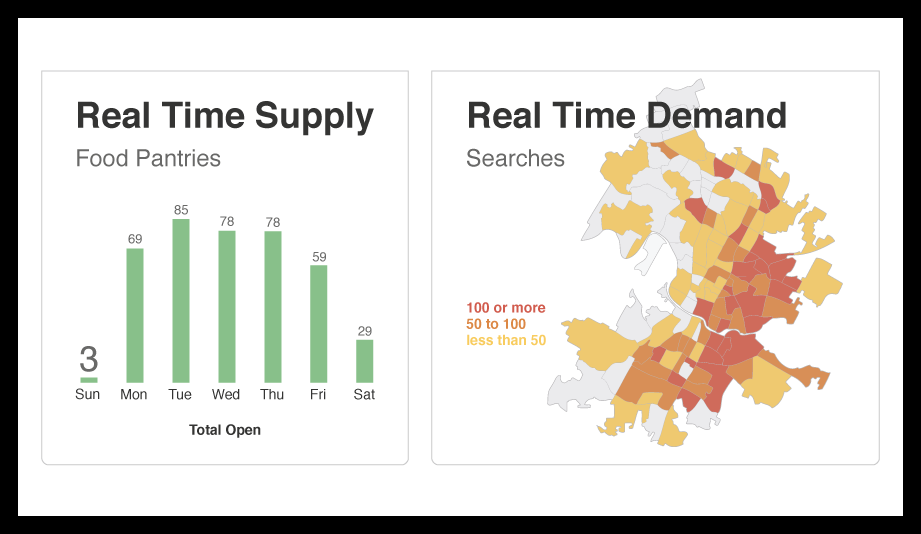

A couple of months ago we launched a real-time analytics platform that allows policy makers and advocates to see what people are searching for, so that they can see the holes in services in their community. For a pilot we did in Richmond, Virginia, we mapped the concentration of searches. You can put in any date range you’d like to analyze. You can see the history of search growth in that region, but you can also see the searches by neighborhood. If I drill into a zip code I can see—anonymously—exactly what is being searched for. And it’s up-to-the-minute.

What’s really cool about this is that policy makers and city workers can say, “Hey, why is it that so many people search unsuccessfully for, say, assistance with ‘light bills’?” It could be we just don’t have that need addressed in our database. Or, as in this case, we didn’t anticipate the search term the seeker used. Once we pinpoint that, we can add it as a synonym to our taxonomy, and redirect people to what they need—in this case, utility assistance programs.

But the sad thing is that sometimes there just are just no services. That’s what we’re trying to solve. We make search data available to policy makers, researchers, universities and so on, so that they can better understand where the hurt is in their community. Imagine a world where you can see, in real time, that your neighbors don’t have enough money for tampons. This is a real search: every single search is somebody’s life. It’s somebody’s crisis moment.

But how can a policy maker respond to a need so specific and small, in real time?

Not very well, honestly. But they can aggregate the information and say, “Let’s give $500 dollars a month to the local food pantry and ask them to stock sanitary supplies,” and then change the listing. The thing is, most cities and most foundations have full-time people dedicated to understanding the needs in their city. So this is just another tool to help them do a better job.

The Search Reporting Dashboard, which shows community leaders local search information in real time. Image: Aunt Bertha

How did you find and aggregate so much information? There are government programs, NGOs… what else?

That’s been our biggest investment, and what I worry about the most—making sure that the data stays current. Unfortunately, there’s no magic source of this data. There’s little bits and pieces of open government data, and it’s pretty poor quality. We start with the very basic information that is available—like IRS charity data—and then we built a series of automated jobs that can check program websites to grab information like hours of operation, email addresses and phone numbers. Every now and then people will send us a list of programs they’ve put together.

The nice thing is, it’s not something that has to be done all at once. We just launched a feature that allows programs to claim their listing. And we have some other experiments we’re working on. The reality is that it’s going to take lots of different channels to keep the information current. There’s no silver bullet. We just roll up our sleeves and work through one program at a time.

It’s a complicated problem. Some people think we’re crazy for even trying. We may be, I don’t know.

How do you pick the states you’re working with?

Usually someone will reach out to us and start a conversation. We’ve spent a lot of time building a scalable way to collect the data for a geographic area. Usually, if someone reaches out from rural areas or small cities, we’ll have our data entry team collect that data pretty quickly — in days or weeks, not months. Our Chief Information Officer, Stu Scruggs, really has made it easy. So if anybody’s interested in bringing Aunt Bertha to their city, just reach out to us.

One organization that we’re particularly excited to be working with is called Critical Mass. Critical Mass is developing strategies to overcome the barriers facing young adults with cancer. We’re working on a really cool project that is making it easy for people diagnosed with cancer to find targeted help in seconds. We’re also working with great organizations like Heartland for Children, which is working to eliminate child abuse and neglect in Central Florida.

Our mission is to make human services information accessible to people. And we’re inspired by the innovative government agencies, cause organizations and direct-service non-profit organizations that are out there.

What’s your business model?

When I had the idea for Aunt Bertha, I was originally considering incorporating as a non-profit. I went to dinner with a local entrepreneur, Gary Hoover. He pointed out that our customers would be non-profits, foundations and government entities. His advice was that we really didn’t want to be in a position where we would be competing with our customers for donations. So he challenged me to come up with a scalable model that would keep the doors open.

So we have two products that we sell—essentially we digitize the application process and integrate it into Aunt Bertha—and agencies subscribe monthly to our service. You see, a lot of non-profits don’t have an easy way of accepting applications online, so often seekers just go stand in line rather than submit digitally. Our product makes it possible for seekers to quickly apply for services, and it’s customizable to each agency. So we launch in an area, and then we take a leap of faith that somewhere along the line, some of the agencies in that city or state will hire us to digitize their application process. That’s essentially our business model.

Hopefully we’ll soon have enough customers to cover our expenses and allow us to grow. In the interim, we’ve raised investment from 11 impact investors in the US who are interested in our project and what we’re doing. I don’t know that we’ll be the next Google. But if you can do a good job and love your work and make enough to survive, what else is there to ask for in life?

Reports showing aggregate program supply and aggregate program demand. Image: Aunt Bertha

Do you have any feedback from people that Aunt Bertha has helped?

We’re very protective of our seekers’ privacy and we don’t really ask for testimonials, but we’ve received comments from people who’ve used it for prescription drugs, finding housing and other things. Social workers tell us all the time. An organization called Any Baby Can in Austin, which helps young mothers, use our software to find services while visiting with clients, using their iPads. The feedback has been incredibly positive. People have reached out time and time again to say “Thank you for what you do.” They send Facebook messages. That’s the stuff that keeps us going.

You know you’re offering people relief on a daily basis. That’s got to be good.

We love our job. And we’re lucky to be able to be surviving doing what we love. We get great feedback from social workers who use our site. Just the other day, we received feedback from a neurologist in Colorado who helped a client find cancer resources for his mother. We heard that he had tears in his eyes when he realized there were awesome cancer organizations out there that could help her. Stories like that keep us going for weeks.

Oh, one more question—who’s Aunt Bertha?

Great question! It was a sort of a code name that ended up sticking. Originally it was a play on Uncle Sam—Aunt Bertha picks up where Uncle Sam leaves off. We’ve all had tough times, and need a helping hand every now and then. Almost all of us will at some point in our lives. Everybody has a family member that is a little eccentric, who’s the loudest person in the room. They have good advice, and they tell you when you’re screwing up. I was sort of playing on that. It kind of stuck. But people remember it, and that’s great for our mission.

Comments (2)