Creating characters and stories richly inspired by Arabic tradition, Suleiman Bakhit is fighting to change how the West sees Arab youth — and how Arab youth see themselves — one superhero at a time.

You started producing comics after you got attacked after 9/11. What happened?

I was a student at the University of Minnesota at the time, and president of the international student union. On campus, racial attacks immediately started happening against students who were thought to be Middle Eastern and Arab — whether or not they were — so I was thrust into a position where I had to do something about it.

I started an awareness campaign and started contacting newspapers, senators and so on. The state district attorney got wind of it, and we had a big event where he came to campus and apologized to all international students. This got a lot of media coverage. Shortly after this, four college kids attacked me on my way home late one night. They started with racial slurs, then attacked me with beer bottles. I suffered many scars and injuries that led to surgeries.

As I recovered, I thought, “Well, either I pack my bags and go home to Jordan, or I do something.” And I decided the best way to fight racism is to start with the young. So I began talking to schoolchildren ages 6 and 7 about Middle Eastern culture and what happened to me on 9/11, spreading a very simple message: Not all Middle Easterners are terrorists, and Al Qaeda is like the KKK.

How did they respond?

They loved it! Actually, I’m a scary-looking guy, because I have a lot of scars — so I did have to break the ice. As soon as I got into the classroom, I’d ask, “Do you kids remember Aladdin and Jasmine?” They’d say, “Yeah, yeah.” Because you know, all the kids have watched Aladdin. And I’d say, “Jasmine is my ex and Aladdin stole her from me, and it really pisses me off!” The kids would just burst out laughing.

I also used to bring with me a really nice small carpet from the Middle East. I’d say, “Guess what this is?” And the kids would go crazy. “Yes, yes! It’s magic carpet! Make it fly!” I’d say, “I’m sorry, but it only works in really hot weather. It’s only works in the desert.” In Minnesota, eight months of the year it’s snow, so it worked out perfectly. That’s when I first started realizing that mythology and stories have such great power to bridge cultural divides.

And they wanted to know whether there were any Arab superheroes?

Yes, they were really intrigued by what kids in the Middle East do, read, believe. They asked, “Is there an Arab Superman? Is there an Arab Batman?” I realized that actually, no, there aren’t any Arab equivalents to Western superheroes. Yes, there’s Aladdin and Sinbad, but no one has ever done an animation or comic book based on the actual mythology from within the culture.

I couldn’t get this question out of my head, and did a couple of years of hardcore research, reading ancient texts, doing six month’s archeological research in the Arab desert. I even learned Hebrew. I wanted to read Aramaic so I could read the Dead Sea Scrolls for inspiration. Meanwhile, I started to teach myself to draw, and came up with some characters based on my knowledge of Arab culture. It was a journey towards discovering my own culture more than anything else.

Eventually, I became so convinced that this was my calling — creating characters and stories based in Arab tradition to spread the culture of tolerance — I dropped out of my master’s program in human resource development, went back to Jordan and in 2006 registered my company, Aranim — which comes from a combination of “Arab” and “anime”. (There is no Arabic word for animation, so I had to come up with something.)

What kind of experience did you bring to creating a comics and media business?

I’ll tell you something funny: I’d never drawn in my life! In fact, I once had an art teacher who refunded my parents’ money and advised me never to try again. And I had zero experience in the comics industry — nobody does, in the entire Middle East! So I just learned through trial and error. But I’m a very quick learner and a very hard worker, and working with other artists and writers in my company helped a lot. In my experience, effort always trumps talent.

I have a team of writers and artists working with me. My role is to develop the concepts, characters and stories, and run many focus groups to gauge what kids respond to. In this sense, Aranim’s characters are youth led.

When it came to game development, I hired some misfit programmers here in Jordan and we learned from scratch how to program games. We bought books on Amazon and literally taught ourselves how to program, using blogs and online communities for support. And we did it! We’re the only Arab company in the entire Arab world that creates social games in-house at the quality that we do. As a testament to my team and their hard work, just recently we won a bid by an international nonprofit to create a massive city-building social game to teach youth positive social values when it comes to urban planning.

Tell us about some of your favorite characters and stories.

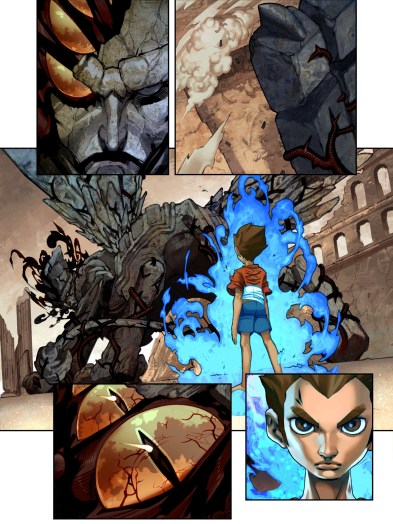

All my stories have deep Middle Eastern mythologies ingrained in them. For instance, in my research, I discovered that in ancient Arabic mythology, fire has seven types, each color corresponding to a different one. So I gave Naar — which means “fire” — the first hero of my first comic, the power of the seven flames. The story is about a group of kids who wake up in a future post-apocalyptic Middle East to discover they have superpowers.

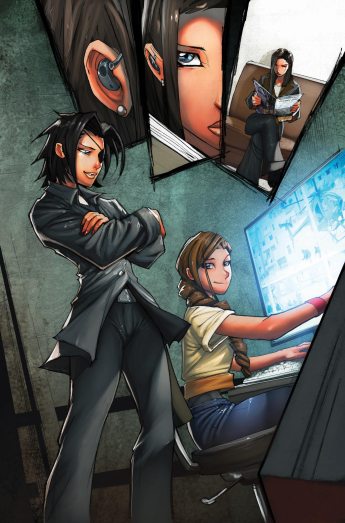

Another title coming up, Section 9, is based on Jordan’s real-life all-female counterterrorism team. I am a strong believer in empowering young women, and it’s a great story to help address the issues they face in their work, society and culture. At the same time, it encourages young men to see that girls can kick ass AND be feminine.

I’m also working on a modern retelling of the One Thousand and One Nights story, and a vampire story based on an ancient text. Did you know that the very earliest written record of any creature that sucked somebody’s blood happened here in the Middle East, in ancient Babylon? There’s a beautiful mythology behind it.

One of my favorite current characters is called Element Zero — he’s a special agent, kind of the Arabic Jason Bourne or Jack Bauer, who fights terrorism locally. One of the first social games we produced is based on this character and story. Within the first couple of weeks of posting the game and comic on Facebook, we got 50,000 players and readers.

Have you seen evidence of your games generating passionate discussions among kids?

When we posted the Element Zero game, young kids came into the forums and started fighting among each other about religion and politics. Worried it would turn into a platform for hate, I posted as game creator: “Kids, stop it. If you keep this up, I’m going to stop the game.” Their overwhelming response was: “This is not your game. This is our game now, and you have no right to turn it off.”

At the same time, I noticed I was getting a lot of fan mail letters for the character himself from girls on the board. So I logged into the forums as Element Zero, and through his character asked them to stop. Within one day, everybody apologized, and that conflict never happened again. That shows you the power of indigenous characters and stories, if people believe in them. This is a big difference. Jack Bauer and Jason Bourne are both great characters with great stories. People love them, but don’t identify with them or feel the same sense of ownership.

Do you generate a lot of controversy publishing these comics?

When I first started publishing my comic books, especially the ones that fight extremism and terrorism, I got attacked outside of my office by a couple of extremists. One of them hit me with a razor blade in my face. He was trying to take out one of my eyes. Because it was late at night and I drive a motorbike, I had to cauterize my own wound with a pocketknife before getting to a hospital. That’s how I ended up with a big, massive scar on my face. But … I got attacked by racists in the US and extremists here — so I must be doing something right.

What’s next?

We’ve got 30 comic book titles, but we’re moving away from print to digital publishing because print media is dying and just too expensive. Hopefully by the end of this year, we’ll have all the comic books available in English, and by summer, hopefully, on the iPhone and the iPad. And we plan to go international — I publish in Arabic, but when we go fully digital, we’ll also publish in English.

I’ve also currently got four games and two more in development, and we’re about to release our first iPhone game in March — a combination of the Arab Spring and Animal Farm. We’re also moving into TV and film: I’m producing two live-action shows, one a web TV show based on Element Zero character. One of the top Hollywood studios is interested in that story, too. I’m also producing my first live-action, low-budget feature, a horror story based in Arab mythology.

But it’s not really about the media. It’s about the characters and getting them out into the world to send a message. When people tell me, “You’re a comics creator,” I reply, “I create stories. Whether its presented as a comic or as a game or as a movie, it doesn’t matter.”

How has being a TED Fellow had an impact on your life and work?

Being a TED Fellow came at the best time in my life. I couldn’t have asked for a better gift in that moment. And what’s really amazing is, when I did my TED talk, it was on my birthday! The experience really helped remind me of why I do what I do, during a very difficult period in my life. I had zero funds at the time, and we’d just released the first game. During the conference, I got great coverage, and suddenly, we were one of the hottest startups in the Middle East, and we won a major investment deal from one of the largest TV and media networks in the region as a result. It shut down all the critics. I was also the first Jordanian entrepreneur to become a TED Fellow. So it was exciting on both personal and professional levels.

And here’s another story that’s a testament to the impact the TED fellowship has. During the time of the Libyan civil war, another TED Fellow, Adrian Hong, and I found out through our contacts that there were a lot of injured civilians that needed medical attention. We started lobbying, creating sort of a channel between Libya and Jordan to try and help some of the injured civilians come to Jordanian hospitals. The ball got rolling, and I am happy to say that over 15,000 injured civilians got treated in Jordanian hospitals. Adrian and I played a very, very small part. But, like they say at TED, “big ideas”. This was a small idea, but people jumped on board and it took on a life of its own.

So are you going to translate any of your print comics at all for young American audiences? Because, after all, they’re the ones who inspired you!

Absolutely. One day, I will go to that same classroom and give them the comic books for free, and answer that question, finally.

Comments (14)

Pingback: Bam! Pow! : The Jordanian who Fights Terrorism with Comics : Euphrates Institute

Pingback: Middle Eastern Comics Battle Terrorist Ideologies | Comic Book Legal Defense Fund

Pingback: Suleiman Bakhit – Creating Tolerance Through Comic Books | We Had Homework?!?

Pingback: Suleiman Bakhit – Creating Tolerance Through Comic Books | The Masked Bagel

Pingback: Suleiman Bakhit – Creating Tolerance Through Comic Books | Gum Drop Buttons

Pingback: Alpha Male Squadron

Pingback: O Walt Disney do mundo árabe | My East-West

Pingback: Jamaican Avengers? « Social Research Central