Thandiswa brings a rocking, soul-deep performance to kick off Session 5 of TEDGlobal 2017 on Tuesday, August 29, 2017, in Arusha, Tanzania. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

The speakers in this session are artists, designer-scientists and visionaries who are remaking the world around them. Their weapons are scope, shutter, paint, brush, font, code, blood and bone. And they are not afraid to use them. Who are they and what do they want? It’s time to find out.

Self-styled “wild woman” Thandiswa Mazwai came off as both fierce and vulnerable in tonight’s performance with her band. Some people in the audience reported getting goosebumps. Brrrrr. Others report 🔥.

To recover, we watch this lovely short film featuring TED Fellow Walé Oyéjidé, a lawyer turned fashion maven for the menswear line Ikiré Jones. Their vision brings traditional African prints to tailored menswear, blending cultures, traditions and signifiers to make gorgeous stuff.

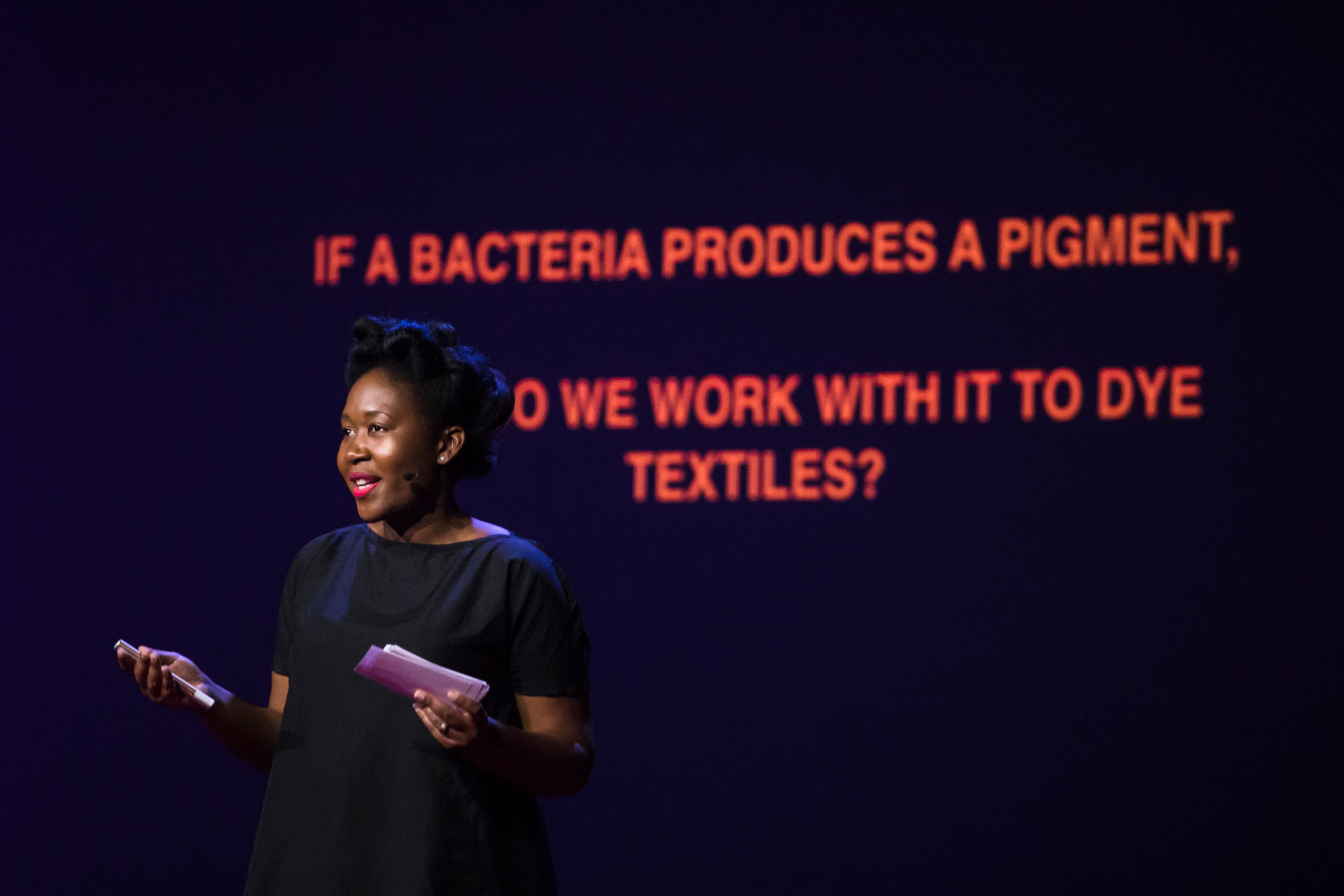

Over the past century, our world has organized itself around fossil fuels — “arguably the most valuable material system we’ve ever known,” says Natsai Audrey Chieza. But that system is coming to an end — not only because we’re within sight of running out of fuel, but because our dependence on petroleum has wreaked havoc on our planet and our economies. In her work, Natsai images a world that transitions off fossil fuels and onto biological materials that do the same tasks, are endlessly renewable, and recycle like a dream. As a first step, she shows how naturally occurring bacteria can be used to dye textiles at industrial scale (replacing disastrously dirty oil-based dyes). We have a chance to build a new industry from scratch, she says, that works in symbiosis with the environment. As she sees it, the future of materials will be grown, fermented and recycled.

Natsai Audrey Chieza imagines a world beyond fossil fuels — not just in our cars and homes, but in the many industrial processes that depend on petroleum. Imagine instead an industry based on biology, that grew itself and used itself up with no waste? Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

After a visit to the library in search of Arabic and Middle Eastern texts turned up titles about terrorism, fear and ISIS, Ghada Wali resolved that she would not leave her culture, nor the Arabic script, to disappear. The one tool in her arsenal was graphic design, and while she initially wasn’t sure how that would help, she drew on her recollections of the visual medium’s power to spread messages that led to the downfall of two dictators in her home country of Egypt. With the weapon acquired, all Wali needed now was a mission. “My eureka moment was to find a bilingual solution for Arabic education, because effective communication and education is the road to more tolerant communities.”

The solution that she designed is an appealing mashup of colourful Lego and the Arabic script: a game that teaches people Arabic by assembling Lego blocks. The concept has morphed into merchandise, a mobile app and, very soon, a book. “This book is the final product that I would like to eventually publish and translate into all the other languages in the world,” she says, “so that Arabic teaching and learning becomes easy, fun, and accessible globally.”

“If you look online at a map of a township in South Africa or a remote village in Nigeria, you’ll see a few roads, surrounded by a lot of empty space. But if you switch to satellite view, you’ll see vast swathes of houses, businesses and people there, spread across hundreds of unmapped streets.” Chris Sheldrick wants to help the world’s unmapped people, the estimated billions who live without an address, to get more findable. He and a mathematician friend realized you could divide the world into 3-meter squares (to save you the math, it’s 57 trillion squares). And then you could give each square an absolutely unique name if you just stuck three random words together. (A dictionary of 40,000 words gives you 64 trillion combinations.) It’s nerdy and a bit goofy, but it’s working, in Mongolia, in UN disaster zones, even in a Caribbean pizza delivery service. And this year three African nations — Nigeria, Djibouti and Cote D’Ivoire — are giving it a go.

Throughout his colourful career and bodies of work, Iké Udé has found creative ways to repudiate the negative portrayal of Africans — most recently, through the evocative images of a portrait series, Nollywood Portraits: Radical Beauty. “Nollywood is Africa’s vivid mirror par excellence,” he enthuses. “It is the very first time that you have a school of Africans truly in possession of such cultural agency and in charge of telling African stories, for their Africans, without any foreign or colonial intervention.”

He observes that the age of social media and YouTube has actually helped to advance the ubiquity of Africans. But he doesn’t seem quite ready to down his tools just yet. “Part of my job,” Ude says, is to keep beautifying Africa and the world, one portrait at a time.

Iké Udé’s astonishing self-portraits blend clothing, props and poses from many cultures at once into sharp takes on global visions. Photo: Bret Hartman / TED

Sethembile Mzesane became uncomfortable with the horde of masculine and racist symbols that loomed everywhere in Cape Town, the city she had lived in for five years. “I could not see myself represented, I could not see the women who raised me, the ones who influenced me and the ones who have made South Africa what it is today. I decided to do something about it.”

And something, she did. She became a living sculpture, standing for hours on end in public spaces. Each time, the deliberate combination of the symbol she chose to embody and the places she chose to perform in never failed to evoke powerful reactions from the people who went past. One time, she stood barechested in a place called Freedom Square to protest the treatment of women at a local bus depot. Another time, she became Chapungu, the soapstone bird that was looted from Great Zimbabwe, and stood triumphant while the cranes took down the statue of John Cecil Rhodes, Chapungu’s plunderer.

“With my work I’ve gotten regular people to talk about the society they live within,” she says. “Through my performances I have made people reflect about the past and the current democracy they are part of.”

Off to a barbecue. Tomorrow at 8:30, we start it up all over again. Tonight, catch up here.

On the day in 2015 that the statue of Cecil Rhodes came down in Cape Town, Sethembile Msezane stood in front of it dressed as Chapungu, the soapstone bird looted from Great Zimbabwe. Her powerful pose reclaimed the space for African identities in a square once claimed by colonialists. Photo: Ryan Lash / TED