Artist Bassam Tariq is determined to shine a light on the incredible diversity of Muslim life – and he does it by any means necessary. Known for his blogging project 30 Mosques in 30 Days, Tariq and a friend took a month-long road trip through all 50 states, breaking their Ramadan fast each evening in mosques along the way and documenting the people they met.

Artist Bassam Tariq is determined to shine a light on the incredible diversity of Muslim life – and he does it by any means necessary. Known for his blogging project 30 Mosques in 30 Days, Tariq and a friend took a month-long road trip through all 50 states, breaking their Ramadan fast each evening in mosques along the way and documenting the people they met.

He also traveled to Pakistan to film These Birds Walk, a documentary celebrating the life of the unassuming man who created Pakistan’s first ambulance service, through the lens of a coming-of-age story. And if that’s not enough, back home in New York City, Tariq cofounded Honest Chops, a halal butcher shop in the East Village that offers high-quality meat to his neighbors, 90 percent of whom aren’t even Muslim.

As his TED Talk, “The beauty and diversity of Muslim life,” is released, we spoke to Tariq about the unifying vision behind these wildly disparate projects, and how they each serve to alter perspective on what it means to be Muslim.

Your arsenal of talents is somewhat bewildering — butcher, blogger, filmmaker. How did you get here?

I was born in Pakistan, but after a short time in New York, where we lived in a very middle-class Astoria neighborhood, we moved to Houston — to the hood — when I was about 11. We didn’t even realize how bad the neighborhood was at first, because New York was so dirty in the ’90s. It was a subsidized housing complex. We thought, “Wow, this is so nice and so big!” It turned out to be violent.

I realized that everything was divided by race. It felt really weird, because in New York, we all just got along and everyone was from a different background. This neighborhood was a predominantly African-American area, and we were the only brown kids, and we always got into fights — always. So I started lying to people, and told them I was Jewish, just to get around. I didn’t want to be called “Gandhi.” To me, that was the worst thing you could be called.

I can think of worse people to be.

I know, right? But my attitude was, “That stupid little Indian man ruined everything for me.” They’d show videos of him in school, and everyone would be like, “Yo, that’s your dad.” And I was like, “Oh my god. No, I’m Pakistani.” People would respond: “What’s that?” No one really even knew where it was on a map.

Then, when we moved into the suburbs, we lived among more affluent people. It was the first time I started seeing a lot of white people in my life. I was in ninth grade. And I thought, “This is weird. These are American, WASPy white people.” Very different from the Greek and Italian kids that I grew up with [in New York]. That’s when I started seeing a different side of privilege. Until then, I believed our problems were due to having a victim mentality. When I went to college, I got involved with student organizations. The pivotal point for me was 9/11. I was forced to deal with Islam and what it meant to me — if anything. It’s such a cliché. But our politics and beliefs were put in the spotlight.

I also met affluent Pakistani kids who grew up wealthy, and until then I had no idea what that wealth was like. My dad worked in a restaurant, and we owned a gas station — that was our upward mobility — and we weren’t particularly religious. My dad would open the doors to the mosque in the morning, and then he’d go to open up the gas station. Later, we closed the gas station and my dad then opened a Chinese restaurant.

How’d that go?

It was really good food — Pakistani-Chinese fusion. It was awful as a business; it only lasted about a year-and-a-half. But my dad’s a great cook.

Above, watch the trailer for These Birds Walk, Bassam Tariq’s documentary feature that follows the coming-of-age story of two boys in Pakistan.

What did you grow up thinking you’d do?

I thought I’d go into business, or maybe become a doctor. I was the first one in my family to get to go to college, so it was a big deal. But during that time, because my parents couldn’t afford college, I was signed up as a subject for medical tests to make money. It was dehumanizing. They’d hook me up to these weird machines and feed me medicine, and then follow my heart rate and so on. Then I took this class called “Creativity in American Culture,” and that really shifted my perspective on what was possible. I picked up a camera and thought, “I’ll start shooting videos. That might make some money.” I learned how to edit from a friend, and then did corporate videos — like videos for the university mental health department, and so on.

Is that why you became a filmmaker?

Yes, but I didn’t have an interest then in the art of film. In the beginning, I was excited about the creativity of advertising, and that’s the route I took after I graduated and moved to New York. It was really tough, being the only non-white person in the creative world of advertising. It’s very, very homogenous, and there’s no nuance to stories. There’s a façade of creativity, a sense that you’re changing the world. But I saw through it, and I ultimately got axed from my first job due to my lack of interest.

How did end up making These Birds Walk?

When I went to New York, I wanted to get away from Muslims, because in Texas, I saw how we bubbled ourselves. But as soon as I got to New York, I ended up meeting Muslims — and they were an amazing group of creative artists. My roommate, for example, was a filmmaker named Musa Syeed. He was setting his own rules, doing things his own way, and he was unapologetic about his beliefs and his practices. Until I met Musa and others in this circle, I’d worried more about being the token Muslim, that my work would be only for Muslims. Even now, for These Birds Walk, it was really important for me to make it about universal themes — family, youth, growing up.

Salaam Ali, a bus driver and poet, prepares for his afternoon bus route in Karachi. Image: These Birds Walk

During this time, I read about a humanitarian in Pakistan named Abdul Sattar Edhi, who started the first ambulance system in all of Pakistan, in the early 1950s. He owned a candy store and had only a fourth-grade education. He sold the store, bought a van, and on the side of the van wrote “poor man’s van.” Then he began transporting the sick and the dead all over Pakistan.

Little did he know it was the first ambulance in the entire country. Today, he runs the largest private ambulance service in the world. He’s old now, and only has two shirts to his name. He takes a shower once a month, has the worst teeth that you’ve ever seen — you would mistake him for a beggar on the street. He is not Mother Teresa — his work is secular — but he’s a religious man himself. But he’s radically independent, doesn’t take money from any governments, doesn’t take money from missionaries. Everything comes from private, local donations.

How did you approach him?

We just went in there, and said, “We want to make a film on you.” He said, “No. Because if you want to know me, you must see me through my work.” He threw us that challenge, and that’s the film. It provides a lens to understand who this man is, and the work of an unapologetic humanitarian.

Tell us about the children in the film.

The story is told from the point of view of an 8-year-old boy named Omar — he’s a real kid. We find him in this little home for runaways that Edhi runs, and he and his friend Shehr are sitting there, talking about their parents. Shehr deeply regrets running away from home. He starts the conversation: “Will our parents bless us if we’ve broken their hearts?” The light bulb went off. These kids made the decision to leave their families.

See, the tragedy of orphans is a little more clear-cut. They have no one, and that’s why they’re where they are. But these runaway kids made a choice. And that element of choice raises the stakes and questions. Can these kids redeem themselves? What does it mean to them to find family, and what does home mean? Abdul Sattar Edhi is part of the context of the story, but then he’s out. We come back to him towards the end of the film, but the hope is that his presence is felt throughout.

Runaway kids from Banaras Colony in Karachi sitting in the corridor of the Edhi Home. They were brought here after surviving a bomb blast in their neighborhood. Image: These Birds Walk

Do you think of yourself as an artist? And is your meat shop art?

I consider myself a worker and some of the work that I do fits into a larger conversation. How I enter that conversation and who I’m speaking to can sometimes be considered art. In terms of the meat shop, it’s funny that you ask that. Having an organic halal butcher in the East Village’s Fashion District does feel like a weird piece of performance art.

What are the communities you serve at the butcher shop?

There are three. Our bread-and-butter clients are the local East Village community, who are the kids of artists, hipsters, people who work in start-ups. They come to us every day, and really love us. Then we have a young professional Muslim community. They’re the ones that order online, and we deliver to their houses. They’re a lifeline for us, because they were the ones that we started it with and for.

We also have a large local immigrant community — the Bengali families, the Chinese families, and so on. These are the people who are overlooked and underserved, and we try to reach out to them. Unfortunately, we are not doing as great a job as we wished. They’ve been in the neighborhood longer than the skinny-jean-wearing hipster — people like us. They’re the ones that want to get out of the neighborhood, but are stuck for whatever reason. I’ll admit: our larger base is the hipsters — the people that go to Mud Coffee, who patronize artisan boutiques. And we knew that they would be the first ones to understand what we were up to.

Breaking into the greater Muslim community is tougher because we have long-held traditions around what a meat store should look like. So your traditional Muslim family might think we’re overpriced from how we look from the outside. But we’re not. You probably spend two dollars more, but you’re getting organic meats from some of the best local farmers.

To what degree are you a butcher? Do you know how to slaughter?

At the store, we all know how to do basic butchering. And yes, I’ve slaughtered a couple of animals in my life. I slaughtered two lambs recently, but I don’t think I could do a steer. It’s too much. It’s a very emotional experience to kill an animal, as it should be. It’s not something you should take lightly. This animal has died for you. I think everyone should do it at least once in their life, if they eat meat. We’re so removed from the process of food production. Part of me thinks it’s okay to be removed from vegetables, because there’s always ground to grow them, but when it comes to meat, and the way we consume meat in the West as people of privilege, is unbelievable.

Tariq opened Honest Chops halal butcher store in the heart of New York’s East Village in Manhattan. Their mission: “To change the world’s relationship to their food.” Photo: Omar Mullick/Honest Chops

How did you begin the 30 Mosques in 30 Days project?

During the production of These Birds Walk, which took a long time and a lot of back-and-forth trips to Pakistan, I was making videos for Time magazine on the side, for income. I’m not a journalist — I didn’t want to be pushed do work just because other people considered it topical. We develop ideas of what is urgent based on current events that the media say are of importance. That’s my problem with mainstream journalism — the reason anyone should care about Islam is because it’s linked to terrorism that links back to America. You end up reducing people to sociopolitical ideas.

In any case, on one of these trips back to New York, it was Ramadan. It was 2011. My friend Aman Ali contacted me and said, “Hey, let’s do this 30 Mosques thing around America.” We’d done it before, the first time just around New York, as a small Tumblr blog. But this time, we decided to visit all 50 states for two years in a row.

When you guys went into these different communities, were you welcomed with open arms?

Generally we were. It’s important to note that being Pakistani men in mosques has its advantages. We are usually given better treatment and accommodations than most. But we were kicked out a couple of times — in Mobile, Alabama, for instance. It was sensitive, because somebody was supposedly an Al Qaeda spy in the community. The media had a frenzy and the community couldn’t afford any more attention.

The journey made me realize that a mosque can restore dignity for a lot of immigrants. For them, it can be a point of pride, and that’s why they want to build these structures, which can be quite bombastic. To me, it’s a little gaudy, but to them, it’s like, “No, this is us.”

So it offers people a focal point.

Yeah, I think it does. And I have to respect that. A community isn’t a structure — a community’s also your warmth and how you welcome people. But I have to admit that going into it that year, we had a very critical eye. We were skeptical in a lot of our writings. So we got a lot of backlash on the way we were writing, because I sometimes questioned or challenged what I was observing.

I also learned a lot about being a New York kid coming in and being critical. A lot of small communities have a complex. “You’re a big-city kid trying to tell us what to do,” they’d complain. They had a point. Who am I to come in, spend literally 10 hours in someone’s community, and write off certain things? But I also felt I had to be able to say, “No, but you also need to stop drinking your own Kool-Aid.”

Muslims in the woods of South Carolina sit together and share stories after they break their Ramadan fast. All of them have become acclimated to the stark darkness of the night. Photo: Bassam Tariq, 30 Mosques in 30 Days

The idea really took off. What did you think when people started mimicking the project around the world?

There were about 20 different communities around the world that started doing 30 Mosques. It was cool to see people in Indonesia doing it, people in Saudi Arabia, people in Malaysia. In one project, “Pink Mosques,” these women decided, “You know what? We’re going to start visiting mosques to see how welcomed we are.” There’s another blog that started by Hind Makki called Side Entrance, which refers to women and their entryway into communities. It’s helped start such a powerful discussion in our community about space.

You’ve been using the term “my community” a lot. Do you mean the Muslim community as a whole?

That’s a good question. I don’t know. It’s a fluid identity, I think. I don’t quite know what it means. I wish I knew. It’s a cross-section of people and beliefs of people that are trying to find a space in a weird world where people are telling us to conform into different standards. We have people from the State Department that are telling us to whitewash our thoughts, that it means “Muslim” is to be somebody that does X, Y and Z — and I hate that. I feel like people in the Muslim community entrench that as well, a little bit. We’re afraid of what people think of us, so we want to put the cutest, smiliest dude on a podium: “We’re Muslim, we’re just like you! Love us!” We’re afraid of talking about things that make us different — the convictions, the rigorous orthodoxy of many mainstream folks. That’s something that I’ve been trying to explore more.

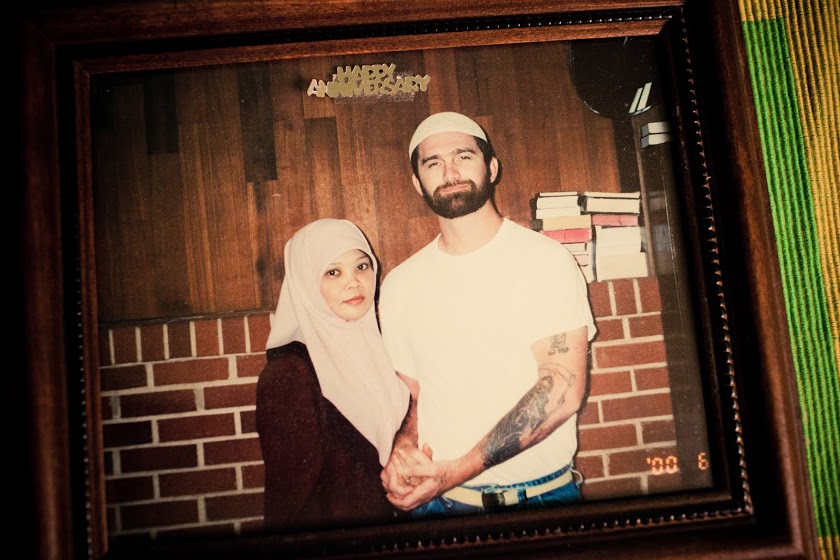

Nur, left, holds hands with her husband, David, for the first time. David was in incarcerated in South Dakota, and they had exchanged letters for years. She met him for the first time the day before this photo. Photo: Bassam Tariq, 30 Mosques in 30 Days

I wonder whether the act of acquiescing to an accepted stereotype makes it a little easier to carry on living a private life without having to defend it all the time.

Yes. And for the projects that I’ve worked on, I have to ask myself, “Are we really doing a better job of communicating these stories of our community?” Sometimes yes, sometimes no. 30 Mosques, for example, was a superficial construct. But in that framework, we were trying to build something inventive. The hope is that it doesn’t read as being apologetic or defensive, but as something that is complicated and nuanced. The power of good art is that it forces the audience to reach their own conclusions. Whatever resolution they come up with, that then also is an understanding of themselves.

How does all this sit with your parents and what they wanted for you? How does it fit in with their experience?

My mother’s message was always to work for someone else, get health insurance, and provide for your family. It’s the standard immigrant dream: live a better life than we did. Make more money, and don’t forget to send money home. That responsibility is an important part of growing up.

I do send money home to my family because their economic reality hasn’t changed much since I was a kid. My mom and dad still work. They’re never going to retire, because it’s just difficult when you aren’t working a professional job with corporate benefits. Social Security might give them a little bit, but not enough. My older brother helps around the house, and he’s the one that works and provides. This makes it easier for me to then do all the things I do. If it wasn’t for my bhai (brother), I don’t know where I would be.

So I feel that whatever I do, it’s also for them. Whatever I do has to be worth it.

A woman prays inside a Muslim women’s shelter in Baltimore, Maryland. Image: 30 Mosques in 30 Days

Comments (3)