“Sensor data can change the game by providing a common source of truth that enables coordinated action required to maintain life-saving equipment,” says Nithya Ramanathan during the Fellows Session at TEDMonterey: The Case for Optimism on August 2, 2021. (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

The TED Fellows are known to be a range of multifaceted souls, making possible the impossible. The eight speakers and one performance on stage at TEDMonterey exemplified this year’s (and every year’s) cohort of amazing people shaping the future and rising to the challenge of making the world better than it’s been left.

The event: TEDMonterey: Fellows Session, hosted by TED’s Shoham Arad and Lily James Olds on Monday, August 2, 2021

Speakers: Daniel Alexander Jones, Tom Osborn, Jenna C. Lester, Alicia Chong Rodriguez, Jim Chuchu, Germán Santillán, Lei Li, Nithya Ramanathan

In a breathtaking performance, Daniel Alexander Jones opens the TED Fellows Session at TEDMonterey: The Case for Optimism on August 2, 2021. (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

Opening the session, performance artist and writer Daniel Alexander Jones evoked the spirit of the Civil Rights Movement with an abridged, rousing performance of the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and closed with a holistic, poetic summary of the talks and the spirit they contained.

Tom Osborn, mental health innovator

Big idea: In areas with limited access to psychologists and psychiatrists, youth trained in evidence-based mental health care can provide support for their peers.

How? Growing up in rural Kenya, Osborn faced enormous pressure to succeed in school and chart a path out of poverty for his family. He suffered from symptoms he now recognizes as anxiety and depression but went without any resources to help him navigate these difficult emotions. As an adult, Osborn works to ensure that the youth in Kenya today have access to mental health support through his organization, the Shamiri Institute. With too few clinicians to serve the population (only two for every one million citizens), the organization trains 18 to 22-year-old Kenyans to deliver evidence-based mental healthcare to their peers. Youth treated through the institute pay under two dollars a session and have already reported reductions in symptoms of anxiety and depression. As Osborn looks to the future, he hopes to use this community-first, youth-oriented model as a template to help kids across the globe lead successful, independent lives.

The harmful patterns and limited scope of diagnosis taught in textbooks and perpetuated in classes around dark skin must end, says Jenna C. Lester during the Fellows Session at TEDMonterey: The Case for Optimism on August 2, 2021. (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

Jenna C. Lester, dermatologist

Big idea: Dermatologists need to get comfortable with all types of skin colors — and that starts with changing what they learn.

How? Just under half of new dermatologists admit they don’t feel comfortable identifying health issues that make themselves known via skin indicators — such as Lyme disease’s “bullseye” — that may show up differently on darker skin. Lester believes this discomfort leads to poorer health outcomes for people with dark skin and proves ultimately detrimental to the patient-physician relationship. So, she founded the Skin of Color Clinic, a program on a mission to help doctors unlearn the harmful patterns and limited scope of diagnosis taught in textbooks and perpetuated in classes around dark skin. She hopes that with her efforts, combined with other similar initiatives around the US, to right the equilibrium of over- and underrepresentation in the dermatological field so that everyone — no matter their skin tone — can have access to quality health and wellness.

Introducing a smart bra that can track and support women’s heart health, Alicia Chong Rodriguez aims to close the gender gap in cardiovascular research. She speaks at TEDMonterey: The Case for Optimism on August 2, 2021. (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

Alicia Chong Rodriguez, health care technology entrepreneur

Big idea: A smart bra that can track and support women’s heart health.

How? About 44 million women in the US live with heart disease, but helpful data is severely lacking. Why? Because most cardiovascular research is performed on men, resulting in therapies largely designed for male bodies. Rodriguez wants to close that data gap — with a bra. By wearing an everyday bra fit with special biomarker sensors, life-saving data could be gathered continuously in real time. The sensors track heart rhythm, breathing, temperature, posture and movement and update this information to the wearer’s records — so that doctors can understand their health better with troves of information to back it up. By simply wearing a bra, she says, we could close the data divide and finally usher women’s health care into the 21st century.

Jim Chuchu, filmmaker

Big idea: Stolen African art and artifacts showcased around the world should be returned to museums and cultural institutions on the African continent.

Why? Why are stolen African artifacts still in the possession of Western museums? Chuchu reminds us, many of these cultural artifacts wound up in cities like London and New York because they were looted by colonial forces. Working to return Kenya’s material heritage to the country, he and the International Inventories Programme, an organization he co-founded, are rectifying these injustices. They have created a database of cultural objects held outside of Kenya — locating over 32,000 items so far. Beyond tracking these precious artifacts, Chuchu also hopes to start a public conversation about the morality of holding stolen African art in foreign institutions. “We’re asking for the return of our objects,” he says, “to help us remember who we are.”

Germán Santillán, cultural chocolatier

Big idea: By training a new generation in Indigenous cacao cultivation and culinary methods, Germán Santillán is helping revive the culinary tradition of Oaxacan chocolate.

How? The Mixtec people in Oaxaca, Mexico have been cultivating and consuming chocolate — in ceremonies like marriage or politics — for over 800 years. However, in Mexico today, four out of five chocolate bars are produced using foreign cocoa. Santillán grew up in a Mixtec village in Oaxaca and watched as ancient Mixtec methods long-used to grow cocoa beans and prepare chocolate fell out of use. To revive the rich culinary tradition of chocolate in his region, Santillán and a small group of locals started Oaxacanita Chocolate. Unlike commercial chocolate bars, their Oaxacan chocolate uses native cocoa beans and traditional farming and roasting methods. Not only does their company produce a delicious product, but it has also helped boost his region economically and train a new generation of farmers and cooks in once-disappearing Indigenous techniques. It’s a powerful reminder of how Indigenous knowledge and practices can thrive in a modern context.

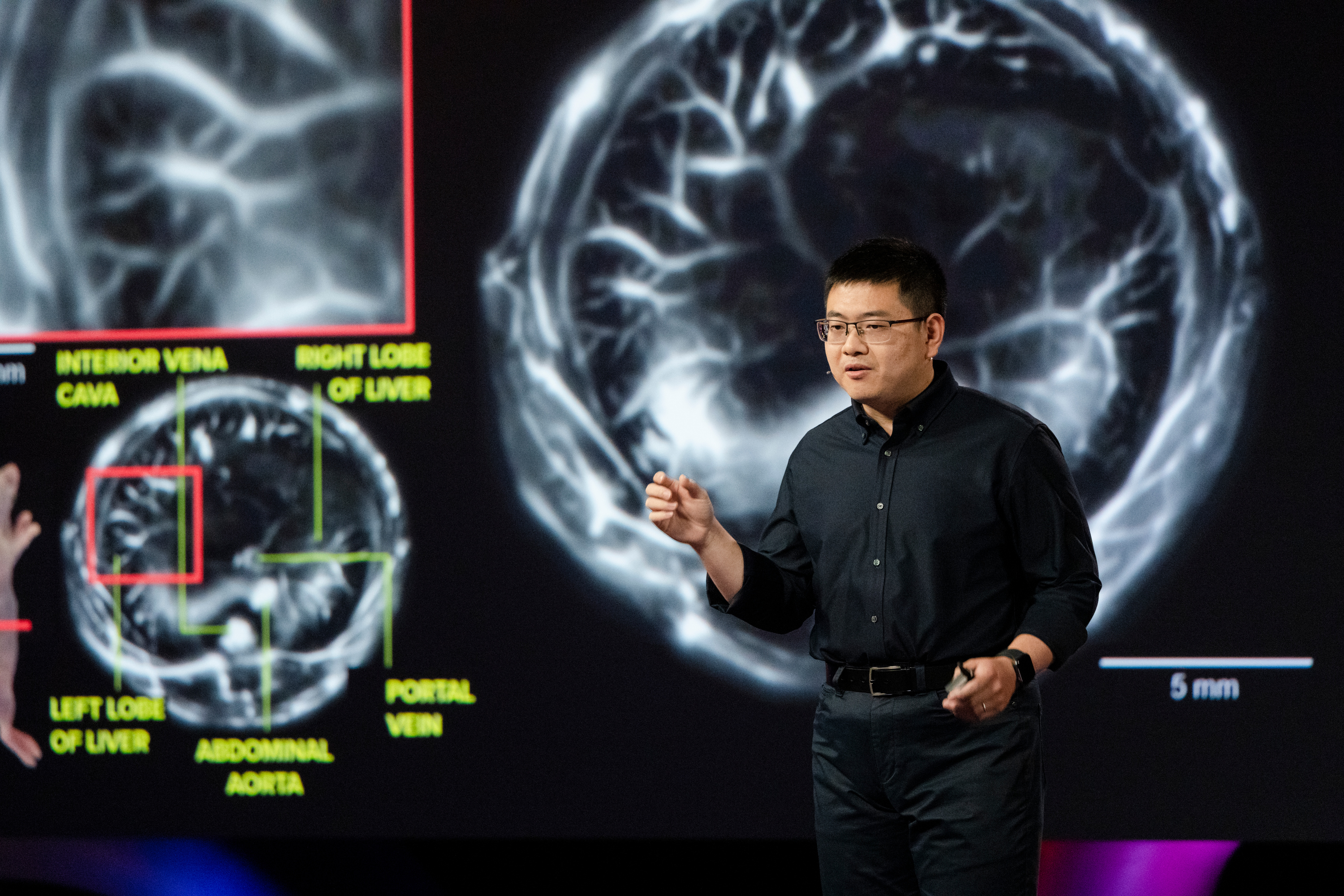

Lei Li shows how cutting-edge photoacoustic imagery will transform the way we see inside our bodies to detect, track and diagnose disease, during the Fellows Session at TEDMonterey: The Case for Optimism on August 2, 2021. (Photo: Ryan Lash / TED)

Lei Li, medical imaging innovator

Big idea: Advanced imaging using light and sound will transform how we see inside our bodies, elevating our ability to detect, track and diagnose disease.

How? The foundation of advanced photoacoustic imaging converts light energy into sound energy, also known as the photoacoustic effect. The process goes like this: Li and his team pulse painless, gentle lasers into living tissue (in this example, he used a mouse), which absorbs the light and rises in temperature, leading to the generation of acoustic waves — or sound — that medical sensors interpret into a high-resolution image. Li shows how the clarity and detail of these images far exceeds those produced by a traditional MRI, CT scan or ultrasound. The applicability of this technology is wide-reaching, from breast cancer diagnosis and human brain imaging to potentially steering medicine-delivering microrobots inside our bodies. Photoacoustic imaging is a fast-growing research field, he says, and the promise for global health is reason enough to sound-off.

Nithya Ramanathan, technologist

Big Idea: Smart sensors are a game changer when it comes to preserving life-saving vaccines.

How? After life-saving technology is deployed to countries with limited infrastructure, Ramanathan realized it is often left unsupported from thereon. Take vaccines for example, if they get too hot or cold on their journey or in storage, they could be ruined before use. Ramanathan talks through real-world examples — one case in particular took place in Stanford Children’s Hospital, where a refrigerator malfunctioning for 8 months meant that over 1,500 kids needed to be re-vaccinated — and the stakes are even higher now with COVID-19. Her solution? Smart sensors in refrigerators where vaccines are stored that monitor temperatures and send out alerts when they are unsafe — as well as data on the best routes to use in an emergency. Ramanathan and her team at Nexleaf, a non-profit she co-founded, have implemented this scalable, cost-effective and vital technology in thousands of locations in Asia and Africa. These simple yet extremely effective tools show what is possible when we invest in collecting and utilizing data.