I’ll never forget the first images of Sebastião Salgado’s that I ever saw. At the time, I was just getting into photography, and his images of the mines of Serra Pelada struck me as otherworldly, possessing a power that I had never seen in a photo before (or, if I’m honest, since).

Sebastião Salgado: The silent drama of photography

In the twenty years that I’ve been photographing, his work has remained the benchmark of excellence. So it was with great trepidation that I sat down with him at TED2013, where he gave the talk “The silent drama of photography,” for a short interview. After all, what does one ask of the master?

Sebastião Salgado: The silent drama of photography

In the twenty years that I’ve been photographing, his work has remained the benchmark of excellence. So it was with great trepidation that I sat down with him at TED2013, where he gave the talk “The silent drama of photography,” for a short interview. After all, what does one ask of the master?

I have so many questions — I’m a great admirer of your work. But let me begin with: why photography?

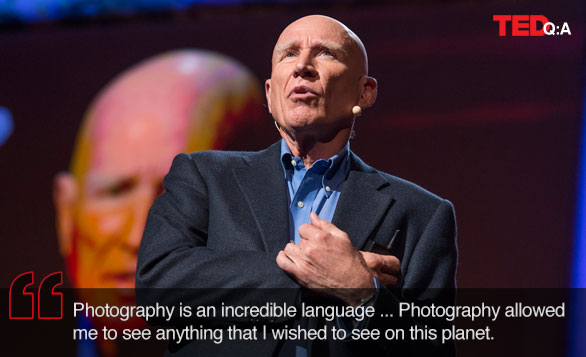

Photography came into my life when I was 29 — very late. When I finally began to take photographs, I discovered that photography is an incredible language. It was possible to move with my camera and capture with my camera, and to communicate with images. It was a language that didn’t need any translation because photography can be read in many languages. I can write in photography — and you can read it in China, in Canada, in Brazil, anywhere.

Photography allowed me to see anything that I wished to see on this planet. Anything that hurts my heart, I want to see it and to photograph it. Anything that makes me happy, I want to see it and to photograph it. Anything that I think is beautiful enough to show, I show it. Photography became my life.

You started as a social activist before you were a photographer. Is that how you think of yourself still — as an activist?

No, I don’t believe that I’m an activist photographer. I was, when I was young, an activist — a leftist. I was a Marxist, very concerned for everything, and politics — activism — for me was very important. But when I started photography, it was quite a different thing. I did not make pictures just because I was an activist or because it was necessary to denounce something, I made pictures because it was my life, in the sense that it was how I expressed what was in my mind — my ideology, my ethics — through the language of photography. For me, it is much more than activism. It’s my way of life, photography.

You do these very large, long-term projects. Can we talk a bit about your process at the beginning of a project? How do you conceive of it? How do you build it in your mind before you start?

You know, before you do this kind of project, you must have a huge identification with the subject, because the project is going to be a very big part of your life. If you don’t have this identification, you won’t stay with it.

When I did workers, I did workers because for me, for many years, workers were the reason that I was active politically. I did studies of Marxism, and the base of Marxism is the working class. I saw that we were arriving at the end of the first big industrial revolution, where the role of the worker inside that model was changed. And I saw in this moment that many things would be changed in the worker’s world. And I made a decision to pay homage to the working class. And the name of my body of work was Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age. Because they were becoming like archaeology; it was photographs of something that was disappearing, and that for me was very motivating. So that was my identification, and it was a pleasure to do this work. But I was conscious that the majority of the things that were photographed were also ending.

When I did another body of work, Migrations, I saw that a reorganization of all production systems was going on around the planet. We have my country, Brazil, that’s gone from an agricultural country to a huge industrial country — really huge. A few years ago, the most important export products were coffee and sugar. Today, they are cars and planes. When I was photographing the workers, I was looking at how this process of industrialization was modifying all the organizations of the human family.

Now we have incredible migrations. In Brazil, in 40 years, we have gone from a 92% rural population to, today, more than 93% urban population. In India today, more than 50% of the population is an urban population. That was close to 5%, 30 years ago. China, Japan … For many years of my life, I was a migrant. Then after that, I became a refugee. This is a story that was my story. I had a huge identification with it and I wanted for many years to do it.

My last project is Genesis. I started an environmental project in Brazil with my wife. We become so close to nature, we had such a huge pleasure in seeing trees growing there — to see birds coming, insects coming, mammals coming, life coming all around me. And I discovered one of the most fascinating things of our planet — nature.

I had an idea to do this for what I think will be my last project. I’ve become old — I’m 69 years old, close to 70. I had an idea to go and have a look at the planet and try to understand through this process — through pictures — the landscapes and how alive they are. To understand the vegetation of the planet, the trees; to understand the other animals, and to photograph us from the beginning, when we lived in equilibrium with nature. I organized a project, an eight-year project, to photograph Genesis. I talked about how you have to have identification for a project — you cannot hold on for eight years if you are not in love with the things that you are doing. That’s my life in photography.

When you do these large projects, how do you know when it is finished?

Well, I organize these projects like a guideline for a film — I write a project. For the start of Genesis, I did two years of research. When this project started to come into my mind, I started to look around more and more and, in a month, I knew 80% of the places that I’d be going and the way that we’d be organizing it. We needed to have organization for this kind of thing, so I organized a kind of unified structure. I organized a big group of magazines, foundations, companies, that all put money in this project. And that’s because it’s an expensive project — I was spending more than $1.5 million per year to photograph these things, to organize expeditions and many different things. And then I started the project. I changed a few things in between, but the base of the project was there.

Given the changes in digital media, if you were to start a new project now, do you think you’d still go through photography? Or would you try something different?

I would go to photography. One thing that is important is that you don’t just go to photography because you like photography. If you believe that you are a photographer, you must have some tools — without them it would be very complicated — and those tools are anthropology, sociology, economics, politics. These things you must learn a little bit and situate yourself inside the society that you live in, in order for your photography to become a real language of your society. This is the story that you are living. This is the most important thing.

In my moment, I live my moment. I’m older now, but young photographers must live their moment — this moment here — and stand in this society and look deeply at the striking points of this society. These pictures will become important because it’s not just pictures that are important — it’s important that you are in the moment of your society that your pictures show. If you understand this, there is no limit for you. I believe that is the point. As easy as this, and as complicated as this.

Comments (17)

Pingback: Three pictures that present wartime pictures can have larger affect than the written phrase – Tip Tech Game

Pingback: Three images that show wartime photographs can have greater impact than the written word - lunaflix

Pingback: Three images that show wartime photographs can have greater impact than the written word

Pingback: Three images that show wartime photographs can have greater impact than the written word | Skeptic Society Magazine

Pingback: Three images that show wartime photographs can have greater emotional impact than the written word

Pingback: Three images that show wartime photographs can have greater emotional impact than the written word | Skeptic Society Magazine

Pingback: Assignment 4 | Mark Racle: Context & Narrative

Pingback: A4 Essay Planning | Mark Racle: Context & Narrative

Pingback: Sebastiao Salgado – photomakers

Pingback: Sebastião Salgado: GenesisVirtual Stylist Gabrielle Rosenberg

Pingback: Wonderful photographs by Sebastiao Salgado | Cyan Photopassion

Pingback: Environment Photographer 2 | Sauntering at the Edge of Heaven

Pingback: Salgado’s message to us all | In Lak'ech: World Perspective

Pingback: ENGLAND, LONDON: Salgado’s message to us all | In Lak'ech: World Perspective

Pingback: Folha de S.Paulo – Internacional – En – Culture – Up Close With Sebastiao Salgado, Brazils Legendary Photographer-Activist – 17/03/2013 | Braziliaans Portugees Leren

Pingback: A new playlist from Sir Ken Robinson, the most-watched speaker on TED.com | Framework Marketing Group....blog thoughts by Randal Dobbs

Pingback: Sebastião Salgado: A gallery of spectacular photographs | RXJ.TVRXJ.TV