By Brigid Jacoby, with Amanda Lynch

November is National Alzheimer’s Awareness Month, a time to pause, reflect and continue the conversation on a disease that touches millions of lives around the world. Alzheimer’s isn’t just a medical challenge — it’s an emotional one that reshapes families, identities and the way we connect with one another.

Every TED Talk begins with a story. Every story begins with a memory. That is the idea at the heart of the TED Memory Project, created in partnership with Eli Lilly and Company. It’s a multi-platform, multi-month movement that explores how memory drives innovation and connection while advancing understanding and empathy around Alzheimer’s.

In his TED Talk, “Where does your sense of self come from? A scientific look,” Anil Ananthaswamy shares: “Take, for instance, the question ‘Who am I?’ The most likely answer you will get or give to such a question will be in the form of a story. We tell others, and indeed ourselves, stories about who we are. We take our stories to be sacrosanct. We are our stories. But a condition that most of us, sadly, will be familiar with, Alzheimer’s disease, tells us something quite different. Alzheimer’s begins by affecting short-term memory. Think about what that does to someone’s story. In order for our stories to form, to grow, something that just happens to us has to first enter short-term memory and then get incorporated into what is called long-term episodic memory. It has to become an episode in our narrative.”

This blog is one way of continuing that work, giving space for voices like Brigid Jacoby’s to reflect on how Alzheimer’s can alter identity and the stories that shape us. It is a space for reflection, where ideas meet lived experience, and where the threads of resilience, grief, curiosity and hope come into focus.

When Brigid watched Anil’s TED Talk, one idea struck her: our sense of self is built on the stories we tell about our past, our families and the choices we have made. Alzheimer’s complicates this deeply because it disrupts short-term memory, the very building blocks of those stories. Without being able to record and recall, the narrative of who we are becomes harder to sustain. “That idea resonated with me because I have seen firsthand how Alzheimer’s can change a person’s sense of self, not by erasing them, but by reshaping how their identity is expressed,” Brigid said.

Anne Jacoby

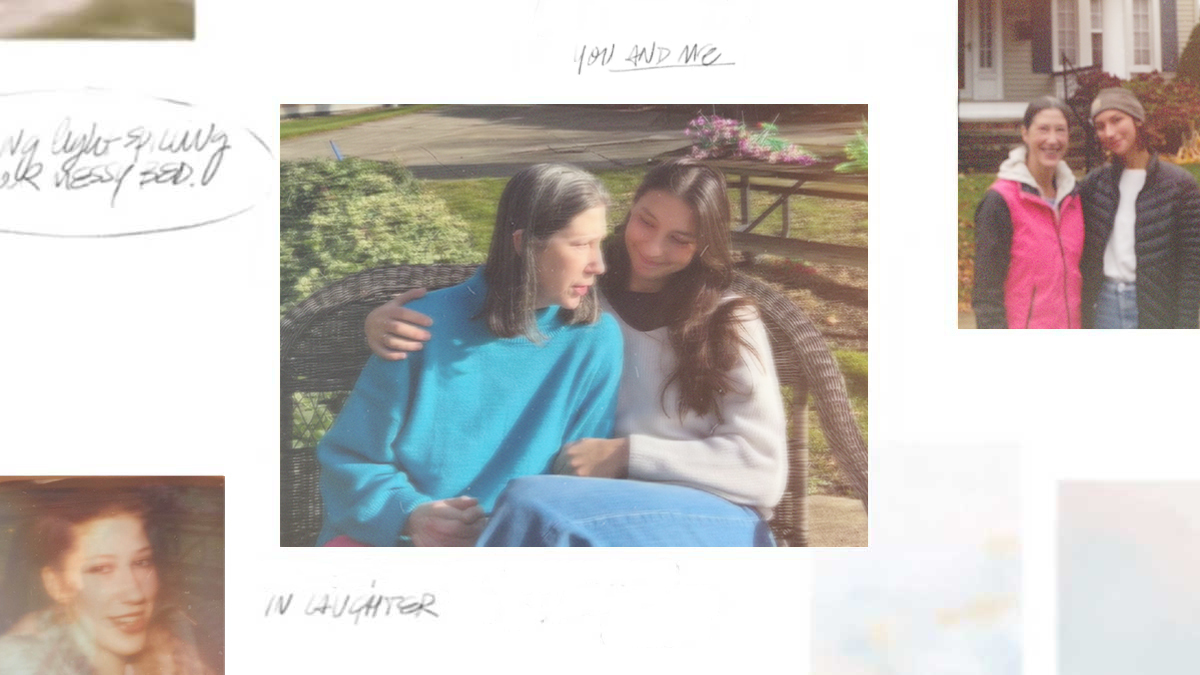

Brigid shares her reflections after the recent passing of her mother, Anne, who lived with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Anne passed on October 30th, 2025, early in the morning, surrounded by her three children. She began experiencing symptoms in her late forties, with her first memory complaints documented at 51. At first, it was small things like misplacing her keys, forgetting dates or struggling with her computer. But soon, the disease began interfering with her work. After more than 20 years in her industry, she lost her job, and even retail shifts became difficult when she couldn’t navigate the digital sales system. Brigid’s younger sibling even took a job at the same shop just to help keep an eye on her.

Anne was a storyteller. As an Irish American, she carried forward the histories of her grandparents immigrating from Ireland, weaving them into a family tapestry she often shared with her children. Her sense of self was tied to these stories and to the act of passing them down.

“One day, sitting outside with my mom, I asked her to retell a story about my great-grandmother,” Brigid recalls. “But this time, I watched panic rise in her eyes as she struggled to understand what I was referencing. The words did not come. Instead, tears did. It was not just memory loss, it was a fracture in identity, the vanishing of a thread she had long held onto as proof of who she was and where she came from.”

Over time, Brigid and her siblings learned to meet Anne in a different place, one not rooted in lost stories but in new ways of being together. They leaned into humor, curiosity and wonder. They asked silly questions, marveled with her at the shape of plants and clouds, or let her imagination spin freely without the pressure of accuracy. In those moments, Anne still expressed herself. Not through the precise retelling of family history, but through joy, silliness and awe.

Anil’s TED Talk reminded Brigid that even as memory fades, the self is not gone — it is simply altered. As Ananthaswamy explains, “I also believe that altered selves should not be seen as the outcome of deficits, or as the outcome of a lack of attributes considered normal. They are different ways of being, and it is the willingness of some of us to confront the self’s constructed nature that is helping make sense of the self for all of us.”

That is why Alzheimer’s awareness matters to her. She wants people to understand that while the disease changes a person, it does not erase them, a lesson she carries forward after her mother’s recent passing. “This awareness gives us tools to show up differently,” Brigid said. “To support loved ones as they move into a new version of themselves, rather than turning away in fear or discomfort. My hope is that people can approach those living with Alzheimer’s with patience, curiosity and care, seeking to understand what they are experiencing instead of mourning only what has been lost. By doing so, we can honor who they are becoming, not just who they were.”

Because behind every statistic is a person like Anne, whose story Brigid now carries forward. And behind every talk is someone like Brigid, reminding us why these conversations must continue.