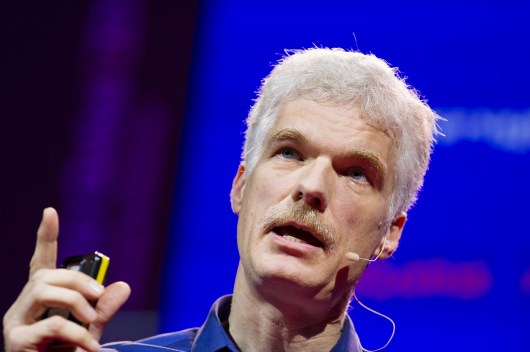

Watch Andreas Schleicher’s TED Talk >>

“Learning is not a place, it’s an activity,” says Andreas Schleicher. He heads up the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment, also known as PISA, and he’s here to make the case that international comparisons of education systems can help to raise the global bar for students and learning.

First, some history, and a needed lesson for the Americans in the audience. Whereas in the 1960s the United States was number one in international education, some countries in the world had caught up by the 1970s, even more by the 1980s … and the trendline hasn’t shifted since. Now, it’s countries such as Korea that are showing what’s possible in education. “Two generations ago, Korea had the standard of living of Afghanistan,” says Schleicher. “Today every young Korean person finishes high school.”

One of the issues in measuring education is to think about the metrics for success. These days, that isn’t simply a question of who gets what degree. What’s needed is skills that will be useful after formal education has finished. “Look at the toxic mix of graduates looking for jobs but employers telling us they can’t find people with skills they need,” Schleicher says. “That tells us that better degrees don’t necessarily translate to better skills, jobs, lives. At PISA we work to change this. We want to test if students can extrapolate from what they know and apply their knowledge in new situations.”

In 2009, PISA measured 74 education systems, and discovered some stark statistics. “There’s a gap of three years between a 15-year-old in Shanghai and a 15-year-old in Chile,” he says. (In fact, the gap is up to seven years between some countries.) These are stark figures, and people in the audience are clearly taking it all in.

As you might expect, PISA doesn’t just look at results; it also looked at the wider picture of culture, counting issues such as equity within society and examining how much of a factor a child’s background might be in the quality of her education. Sometimes background has a huge impact; sometimes it doesn’t. But what’s clear is that no country can afford to have both poor performance and large social disparities. So here’s the question that so many ask: “Is it better to have better performance and disparity? Or accept equity and mediocrity?” As Schleicher shows, it’s a false choice. In fact, a lot of countries combine excellence and equity. Countries such as China, Korea and Finland now provide excellence for all their students, from all backgrounds — and provide an important lesson for other countries trying to challenge the paradigm of education as a way of simply sorting people.

Schleicher also shows that it’s not simply a question of throwing money at the problem. How the money is spent is more important. He contrasts South Korea and Luxemburg. South Korea spends a lot on attracting teachers, on long school days, and on teachers’ professional development. To afford this, they also have large, less expensive classes. Luxemburg spends the same amount as Korea, but in the small European nation, parents and policymakers like small classes. So they’ve invested in small class sizes, which is expensive, and that means teachers are not paid particularly well; students do not have long hours of learning; teachers have no time to do anything but teach.

Since 2000, countries have invested 35% more on education. Are we that much better? “The bitter truth is, not in many countries,” says Schleicher. Again, this is about more than just money; it’s about the system. Schleicher’s home country of Germany did poorly in 2000, prompting soul-searching public debate. As a result, the federal government raised investment in education and worked to decrease social disadvantage for immigrants. “This wasn’t just about optimizing existing policies. Data transformed some of the beliefs underlying German education,” he says. Years later, the changes are paying off.

So what can we learn from those who achieve high levels of equity and performance? Can what works in one context provide a moral elsewhere? “You can’t copy and paste education systems wholesale, but there are a range of shared factors,” Scheicher acknowledges. “The test of truth is how education weighs against other priorities. How do you pay teachers? Would you rather your child be a teacher or lawyer? How does the media talk about teachers? We’ve learned that in high-performance systems, the leaders have caused citizens to make choices that value education.”

What is key: A belief that all children are capable of success. In Japan, in Finland, parents expect every student to succeed, and that expectation influences the children’s behavior. High performers on PISA also personalize learning opportunities and share clear standards so that every student understands what’s required for them. Allowing teachers to have autonomy to understand what needs to be taught — and empowering them to teach it in their own way — helps enormously. “The past was about delivered wisdom,” says Schleicher. “Now it’s about enabling user-generated wisdom.”

Investing in teachers themselves is perhaps most critical of all. The progress and growth of the educators themselves matters, and it’s crucial to create helpful, supportive environments in which they continue to learn. High-performing countries have systems that allow teachers to innovate and develop pedagogic practices, looking past test results and outwards toward life in the world at large.

Perhaps most impressive of all Schleicher’s stats is this one: Within high-performing countries, there is only 5% variation between schools. “Every school succeeds,” he says. “Success is systemic.”

There are limits to the research, Scheicher acknowledges. PISA can’t tell countries what to do; but it can show them what everyone else is doing — and show other policymakers what’s possible in education. “It has taken away excuses from those who are complacent, and set meaningful targets and measurable goals to help every child, every teacher, every school, and every principal,” he concludes. “The sky is the limit.”

Photos: James Duncan Davidson

Comments (11)

Pingback: Australia needs to improve teacher quality | Craig Hill

Pingback: Education Franchise News Renascence School international » Using data to build better education systems: Andreas Schleicher at TEDGlobal 2012

Pingback: “Learning is not a place, it’s an activity” [TED Talk] « Communication Wanderer

Pingback: Public Education Spending « The Sexy Politico's Blog

Pingback: LEARNING HOW TO LEARN | Informed Educational Solutions

Pingback: Using data to build better education systems: Andreas Schleicher at TEDGlobal 2012 « Effective Social & Digital Media Storytelling Blog

Pingback: What We Need To Be Successful « Carpe Bootium

Pingback: Using data to build better education systems: Andreas Schleicher at TEDGlobal 2012 « privateschoolteacher